Book Review: “Bring That Beat Back” — A Stellar History of the Art of Sampling

By Adam Ellsworth

Nate Patrin’s magnificently written and wildly informative new book argues for the artistry of sampling, its potential for beauty.

Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop by Nate Patrin. University of Minnesota Press, 336 pages, $22.95.

It is a well-reported fact that hip-hop was born on August 11, 1973 at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Bronx.

At that date and place, 18-year-old DJ Kool Herc (born Clive Campbell) and his sister Cindy threw a party to raise funds for Cindy’s back-to-school wardrobe. The Jamaican-born Herc manned the turntables, and he began his set with the not-yet-cool-in-the-U.S. reggae sounds of his birthplace. The audience was unimpressed, so Herc pivoted to funky R&B like James Brown’s “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose,” the Incredible Bongo Band’s “Bongo Rock” and “Apache,” and “The Mexican” by Babe Ruth. Those tracks hit. The rest is history.

Knowing what songs will fill a dance floor is a skill in itself, but Herc did more than just drop the needle on the right jam. Herc put an emphasis on tunes that made heavy use of “the break”: the percussion-heavy part of a song that made everybody want to bust out their best moves. He then went one step further, and used two turntables to switch back and forth between two copies of the same record. This allowed him to stretch a few bars into a few minutes. And then Herc went further still, taking the break from one song and blending it into the break from another song, and then another, and then another, to create what he dubbed the “Merry-Go-Round.”

Herc inspired countless imitators, and a few of his direct descendants (Afrika Bambaataa for one) made their own genuine contribution to the history of hip-hop. None had a greater impact than Grandmaster Flash.

Born Joseph Saddler, Flash recognized early on in his DJ career that he could never compete with the overwhelming power of Herc’s sound system, or have a record collection as deep and diverse as Afrika Bambaataa. To stand out, Flash decided he’d become the DJ equivalent of a guitar hero and win the audience over with his turntable technique. This led to his “Quick Mix Theory.”

The Quick Mix Theory required Flash to ignore a cardinal rule of DJing and actually (*gasp*) touch the vinyl spinning on his table. Flash would find the break he wanted on a record and then use a crayon to draw a line denoting where the break lived. In doing so, he could literally see the break as it spun around and around. So while a record was playing on one turntable, he would spin the rotating black disc on a second turntable backwards until he hit that exact point he wanted, hit his crossfader, let the second record go, and the break would come in at the exact spot he wanted. Before Flash’s innovation, locating the break was a drop-the-needle-and-pray situation, even for seasoned DJs. After Flash, it was an art that could be perfected.

Flash expanded his repertoire after a happy accident. He realized that, if he missed his mark, he could manually push the record into place, on the beat, and while doing so create a scratch noise. Once “scratching” became a part of his act, Flash wasn’t just using his turntables to play records, he was truly playing the records. The turntable was now an instrument in its own right.

In time, Flash acquired the Furious Five, a group of five MCs whose main job was to hype the audience and rap Flash’s praises while the DJ wowed the crowd with his expert turntablism. In 1978, New York art world scenester Fab 5 Freddy proposed that Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five make a record, but Flash balked. To that point, hip-hop was a live, in-the-moment experience — to make a recording of it seemed like a bizarre idea. Eventually they gave in, but despite Grandmaster Flash’s top billing in his own group, singles like “Freedom” and “The Birthday Party” focused more on the skills of the Furious Five. 1981’s “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel” was the first release to showcase Flash’s techniques as he jumped from record to record — including Chic’s “Good Times” and Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust” — to create something totally original.

“The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel” was a masterpiece, but it didn’t sell. Flash and the Furious Five’s breakthrough would come the following year with “The Message,” a song that nearly 40 years after its release is still considered one of the greatest hip-hop tracks of all time, primarily because of its lyrical brilliance.

“The Message” is unassailable, and while it wasn’t the first hip-hop song with lyrics to touch on social issues, it was the first such tune to make such an immediate impact. “The Message” is also the moment — if you need to point to a single moment — when hip-hop stopped being about the DJ and began to spotlight the MC. So much so that while the label on the wax reads, “Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five,” Flash doesn’t appear on the record at all; the music on the track was performed by live musicians.

Grandmaster Flash — he represents the old school of multiple records spinning (and scratching) on turntables.

As Nate Patrin puts it in his magnificently written and wildly informative new book Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop, “By the time ‘The Message’ changed the game, hip-hop had ceased to center the DJ, with MCs taking supporting roles as crowd-pumping hypemen. Now it was an art form largely dictated by rappers — the ones who could act as the charismatic frontmen or a tight ensemble cast, who didn’t even need somebody else’s old records providing breaks behind them when they could just get some state-of-the-art synthesizer technology to get the dancers moving.”

Hip-hop was barely out of its infancy, and already a major shift in the genre had occurred. But it’s not as if DJs, producers, or samplers became extinct. As Patrin explores in Bring That Beat Back, even when these innovators were in the background they continued to push the boundaries of hip-hop — and sampling has been their primary tool.

Bring That Beat Back centers on four groundbreaking artists: Grandmaster Flash, Prince Paul, Dr. Dre, and Madlib, but it also gives ample coverage to DJs/producers including Q-Tip, RZA, J Dilla, Marley Marl, the Bomb Squad, 187um, and a laundry list of others. The book’s four stars serve as guides through Patrin’s history of the origin and evolution of sampling and hip-hop. Grandmaster Flash represents the old school of multiple records spinning (and scratching) on turntables. Prince Paul epitomizes the early pioneers of what we now think of as sampling as well as the expansion of the genre’s sonic footprint to include jazz. Dr. Dre stands alone as the near-billionaire superstar DJ, but he also embodies the rise of hip-hop on the West Coast and the “g-funk” sound. Finally, Madlib reps a more modern form of sampling, traditional in its crate-digging connoisseurship, but completely modern in its commitment to bending the rules and expanding hip-hop’s sound.

Along the way, Patrin highlights the technological developments that have developed sampling. He starts with the early days of “pause tapes,” which is exactly what it sounds like — play the portion of a song you want on one cassette deck while recording the tune on a second deck. When the portion of the song you want ends on the first, hit “pause” on the second, rewind the first back to the desired starting point, rinse and repeat. He ends up with machines designed expressly for the purpose of being “samplers.”

Regardless of the technology used, sampling has always been about finding the right break, or beat, or note, or sound and then fucking with it to create something original. Sometimes this means digging up something no one has ever sampled before. Other times, it means returning to old favorites and squeezing some more life out of them. Bring That Beat Back chronicles some of these old chestnuts, such as “Synthetic Substitution,” a 1973 B-side from R&B singer Herb Rooney, which has been sampled more than 700 times despite the fact that the original song remains obscure.

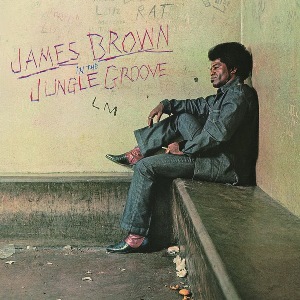

And then there was In the Jungle Groove, a 1986 compilation of recordings cut between 1969 and 1971 by James Brown and the J.B.’s that had an immediate and profound impact on mid-’80s hip-hop. Songs like “Soul Power,” “Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved,” and the immortal “Funky Drummer” became instant sampling staples. These tracks, and other funky as hell songs like them, exerted a profound influence on the sound of at least three albums released in the early half of 1987: Public Enemy’s Yo! Bum Rush the Show, BDP’s Criminal Minded, and Eric B. & Rakim’s Paid in Full. Patrin writes:

All three albums spoke through the echoes of In the Jungle Groove and its peers, the late ’60s/ early ’70s lexicon of funk and R&B that had first inspired hip-hop in its primordial, DJ-driven origins at 1520 Sedgwick. Back then, those J.B.’s and Funkadelic and Syl Johnson cuts were contemporary, or at least recent; but in 1987, they were old classics, memories from childhood or even nods to another generation — the past. And this new wave of producers would build that past into a future nobody saw coming: a sea change in the way music was recorded, reinterpreted, marketed, compensated, and canonized. The MCs were still the stars, but now the DJs were building sounds nobody else could — and ultimately, turning a party-rocking, club-gig profession into something far more historically profound than anyone could have anticipated.

As any comprehensive history of sampling must, Bring That Beat Back also gives attention to the legal aspects of sampling, as well as the very related question: is it stealing, or is it art?

Sampling-related lawsuits are nearly as old as hip-hop itself, but the first major threat to sampling’s survival was brought by members of the Turtles (yes…the Turtles) against De La Soul over the use of the song “You Showed Me” in a skit included on De La’s seminal 1989 album 3 Feet High and Rising. That lawsuit was settled out of court, but a suit brought by Gilbert O’Sullivan (yes…Gilbert O’Sullivan) against Biz Markie over a sample of “Alone Again (Naturally)” turned out to be a game changer. That case set the precedent that it was no longer enough to license a sample, all samples needed to be approved by the original recordings’ creators. “While that ruling didn’t immediately damage the creative potential that sample-based artists and producers were capable of,” Patrin writes, “it went a long way in making the freedom of albums as sample-dense as 3 Feet High and Rising and [1989 Beastie Boys release] Paul’s Boutique prohibitively expensive at best and logistically impossible at worst.”

Legal questions aside, there have always been those who question whether or not sampling constitutes art. Some of these people can be easily labeled as uninformed (if not straight-up racist) and ignored, but not all of them. For example, Patrin writes how in the late ’80s, respected jazz musician James Mtume complained, “We’re raising a generation of young black kids who don’t know how to play music. It’s like learning how to paint by numbers…. that’s based on someone else’s thought and creative ability.”

DJs and producers were unmoved. Hank Shocklee of Public Enemy production crew the Bomb Squad responded, “there is a difference between sampling and plagiarism…. why should I spend eight days to get a snare drum sound like Phil Collins? He’s done that for me. I can sample that in two seconds and get on to more important things.” Daddy-O of the group Stetsasonic fired back at sampling detractors, arguing that the practice was “musical collage,” done in the same spirit as Andy Warhol and his soup cans. Patrin contributes an eloquent defense in Bring That Beat Back. Through sampling, “hip-hop had created a way of recognizing, acknowledging, renewing, and transforming a collective language of musical history that massively expanded the way music itself is listened to: as a mutable object, the calling up of fragmented memories that get the hook or the beat of a song stuck in your head and then make a new world out of that memory.”

Bring That Beat Back acknowledges that hip-hop doesn’t require sampling to exist. Dr. Dre, for example, can sample with the best of them, but he actually prefers the sound of a live band. Southern hip-hop from OutKast, as well as records produced by Timbaland and the Neptunes, skip on samples, and they are among the most groundbreaking and wildly popular releases of the past quarter century. Still, the book shares the conviction of DJ Shadow, whose response to “live-band hip-hop” was the 1996 album Endtroducing….. and the question, “Why are we all abandoning this artform?”

In this sense, the soul of Bring That Beat Back is the DJ/producer J Dilla, who is the main subject of its final chapter. Born James Dewitt Yancey, J Dilla’s first break came as a member of the production collective The Ummah, which also included Q-Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest. As a member of the collective, he worked on Tribe’s fourth album, Beats, Rhymes and Life, which is also the first of the group’s albums to not be considered an instant classic. That was Dilla’s luck. He knew his beats were first-rate, and his hipper contemporaries knew he was a one-of-a-kind, but there were a lot of haters out there.

Dilla was never going to be a mainstream phenomenon, but his luck began to change when he became the beat-making member of Questlove’s Soulquarians crew. His direct and indirect contributions to D’Angelo’s iconic Voodoo kicked off a career resurgence that would include contributions to albums by the Roots, Q-Tip, Common, Erykah Badu, and Black Star. And while Champion Sound, his 2003 collaboration with Madlib, in which the two took turns rapping over the other’s beats, was a commercial flop, it’s considered a cult classic.

That’s where the good news ends. Dilla wasn’t feeling well after a European tour and a trip to the ER led to a diagnosis of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). Shortly after, he began working on some music that was primarily for his own enjoyment and that he knew no MC could rap over. He called the collection of beats Donuts. After playing it for Madlib and Stone Throw Records founder Christopher Manak (a.k.a. Peanut Butter Wolf), they decided the music deserved an official release. The record was too short in its original state, so Dilla continued working on it, finishing Donuts while a patient at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. At times he was so weak his mother had to massage his hands so he could work his sampler.

“Think of the implications of this,” Patrin writes, in the book’s most inspiring passage. “Any other musician in a field playing any other kind of instrument would, under these physical conditions, barely be able to play or perform. The sampling machinery that allowed Dilla to express himself with clarity and creativity that seemed boundless was still able to serve as a direct line from his thoughts to his art, even when it hurt to move. His beats had rarely sounded more vibrant, more alive.” Could there a better argument for the artistry of sampling, its potential for beauty? Three days after the release of Donuts, J Dilla died.

There are no MCs on Donuts. Every “lyric” that appears on the album is actually a sample. Donuts can almost be seen as a throwback to the days of DJ Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash, when hip-hop was all about finding that break, that beat, that sound, and tweaking it until something brand new had been created. Seen in this way, Bring That Beat Back ends where it begins, with the DJ reigning supreme, and hip-hop history waiting to be written.

Note: University of Minnesota Press has complied a Spotify list of all the tunes mentioned in Nate Patrin’s book.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has an MS in journalism from Boston University and a BA in literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.

Tagged: Bring That Beat Back: How Sampling Built Hip-Hop, Dr. Dre, Grandmaster Flash, Hip Hop, Madlib, Nate Patrin, Prince Paul

[…] May, the book has also been covered in Arts Fuse, Scratched Vinyl, Reverb, We Are the Mutants, and numerous other […]