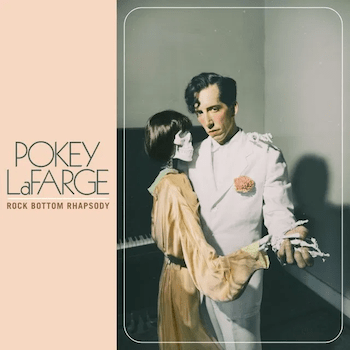

Music Review: Pokey LaFarge’s “Rock Bottom Rhapsody” — To Hell and Back with That Wholesome Midwestern Troubadour

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

In Rock Bottom Rhapsody, Pokey LaFarge shows us where all America’s prophetic manias must lead: collapse.

In biblical terms, Pokey LaFarge’s new album journeys through the wilderness. Or, from an existential perspective, you may see it as a kind of Nietzschean “going under.” It is, as LaFarge characterizes it, a Rock Bottom Rhapsody. And this artist, who cut his teeth hitchhiking and busking fresh out of his Normal, Illinois, high school, has known his share of downers. This album, LaFarge says, follows what he identifies as some new personal lows. Yet the music is also the product of a traditionalist singer-songwriter who is embracing stylistic innovation, expanding beyond his early blues background and into other vernacular styles.

In biblical terms, Pokey LaFarge’s new album journeys through the wilderness. Or, from an existential perspective, you may see it as a kind of Nietzschean “going under.” It is, as LaFarge characterizes it, a Rock Bottom Rhapsody. And this artist, who cut his teeth hitchhiking and busking fresh out of his Normal, Illinois, high school, has known his share of downers. This album, LaFarge says, follows what he identifies as some new personal lows. Yet the music is also the product of a traditionalist singer-songwriter who is embracing stylistic innovation, expanding beyond his early blues background and into other vernacular styles.

Perhaps beginning as early as 2013, with his self-titled album (produced by Jack White on his Third Man label), LaFarge has become comfortable enough to explore new territory. 2017’s Manic Revelations, with its opening heartland rock-infused ballad about the Ferguson Riots, marked a definitive departure for LaFarge’s music and lyrics. That new direction was driven by a need to take an intimate and frank look at his country and culture today. LaFarge was grasping for connections to the past as much as reviving them. Now, in Rock Bottom Rhapsody, our bard shows us where all America’s prophetic manias must lead: collapse. The album was written and recorded during a relocation from St. Louis to Los Angeles, inspired by a romantic opportunity that culminated in a descent into vice and disarray.

America no longer seems to be his reliable artistic subject. What we capture of the country here are visceral scenes rather than faithful visions, more bawdy attitude than blue-collar anxiety. As LaFarge sings: “I’m that wholesome mid-western boy / that you want to bring home to your mama. / Even though I bring you joy / Baby I’m not a toy / You wanna play with at night.” Night has fallen; the arrival of Thanatos on the heels of Eros. Mixed in are elements of soul, country, Roy Orbison, and even French chanson. The album was written before the musician’s self-described “fall from grace,” but it was recorded afterwards: “The man singing these songs isn’t exactly the same man who wrote them,” LaFarge insists. (That is a departure from the LaFarge of 2014, who announced at a TED Talk that “my life onstage, offstage, my music, and my beliefs are one and the same.”) Many of the songs on the new album are languid, melancholic, but never completely enervated… and, in the course of this rhapsody, we recover hope and purpose. Also, something special happens: we see the artist’s personal vulnerability like never before.

In the upbeat opener “End of My Rope” the artist reassesses his life and options: “Growing up was easy, for some, but not me / And getting older is the same old story / They say I’ve come too far / Too late to turn back now / So I guess there’s nowhere else to go.” He then doubles down on his artistic commitment, initiating the rhapsodic narrative to come: “Let the spotlight shine the skin off my bones … making light of my misery.” Following this comes the album’s most popular single, the shockingly titled “Fuck Me Up.” LaFarge stands at Hell’s Gate, warning us to abandon all hope should we proceed. In fact, weak-hearted fans may prefer to turn back, disgusted by LaFarge’s newfound commercialism and lack of class. “I’m that wholesome Midwestern boy,” mocks LaFarge, “that you wanna bring home to your mother.” To see this as a betrayal of his legacy — given such celebratory Midwestern anthems as “Central Time” and “Knockin’ the Dust Off the Rust Belt Tonight” — is to miss a crucial part of what the musician is celebrating. John Waters once affectionately described the aesthetic of his native Baltimore as “white trash chic”… that aesthetic of the deindustrialized heartland is not only full of the virtues of yesteryear, but also of the vices of our day. “Where do I go from here? / The path, it just ain’t clear / So I wanna just leave it all behind.” When LaFarge looks for something to “fuck him up,” he is, sadly, all too aware that his despair is the result of a hopelessness generated by a home suffering from an opioid epidemic.

Rock Bottom Rhapsody also shows us what it is like to long for the elusive artistic muse. First, there is “Bluebird,” an upbeat yet frantic quest to reassemble broken-up inspiration: “She’s got the thing that gives writers the words, the singers sing them in the songs you heard,” he sings, but who is she? “Lucky Sometimes,” an album highlight, proffers a painfully touching, jazzy ode to a love that the singer feels inadequate to attain. Sounding like an early Tom Waits, the narrator talks about “waiting tables at the burger stand” before he finds his muse. But appearances are misleading. LaFarge explains in this notes that this love song was inspired by his move from St. Louis to Los Angeles in 2018, which inaugurated his period of descent. The gorgeous video for the song features Esther Rose as a stand-in for LaFarge’s romantic interest. The story continues: “I wrote you a poem and you bought the drinks at the bar,” and “I don’t deserve nothin, but sometimes you get somethin just for hangin around.” The chorus is as poignant as it needs to be. “Even bums get lucky sometimes,” explains LaFarge.

“Carry On” and “Just the Same” embrace suffering; they are calls to confront our pain. “Fallen Angel” rather triumphantly declares the singer’s renewed strength against such hardships. “You can fall in love with heaven, you can fall in love with hell,” says Lafarge, but “sometimes you never know where you’re at until you’re there.” He ends with the resolution to “never let a fallen angel take me down.” From there we return to the Midwest for the forced isolation of a Chicago snowstorm in “Storm-A-Comin’” before being able to hit the streets again for a cathartic night of drunken spiritual revival in “Ain’t Comin’ Home.” The closer “Lost in the Crowd” limns the sad story of an itinerant musician. However, this time the journey is different. Rather than being at “the end of our rope,” we are at the start of an open highway. No doubt perpetual movement confers comfort on this artist. People, places, and things fade into the mass, including our fallen angel, our fractured muse — lost in the crowd with the rest of us.

Until now, traditionalism was more of a tool than a blueprint for LaFarge. After Rock Bottom Rhapsody suggests that in the future his use of the past will be more flexible … even aspirational. LaFarge’s success continues to open new doors, including acting: he will appear in Netflix’s The Devil All the Time later this year. Note that to “hit rock bottom” also means to hit bedrock. What could be a more natural place for a purveyor of folk traditions to land? Maybe in these days of COVID-19 we should learn what LaFarge picked up — “sometimes you get somethin just for hangin around.”

Jeremy Ray Jewell hails from Jacksonville, Florida. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. His website is www.jeremyrayjewell.com.