Book Review: “August” — A Rewarding Curiosity in the Ordinary

By Drew Hart

August is funny in a way — over time its small-scale rhythms and monosyllabic reactions generate a comforting beauty that settles in.

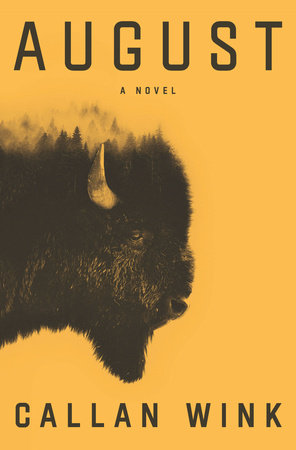

August by Callan Wink. Random House, 304 pages, $27.

Currents in literature ebb and flow — the backwoods and wide-open stomping grounds seen more frequently 40 years ago in the work of authors such as Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Rick Bass, and Norman MacLean haven’t been represented as often or as well in recent years. These writers, often slotted by critics as descendants of Hemingway, captured life in places like upper Michigan and Montana with a keen-eyed verve and poetic detail, even when their stories remained grounded in the matter-of-fact of the everyday. For readers who have been missing this kind of vivid realism, it’s pleasing to report that a successor to this writing school has emerged. Callan Wink has numerous published stories to his credit — some collected in 2016’s Dog Run Moon — and he has just completed a first novel, August, which quietly carries the flame forward.

The title here doesn’t refer to the summer month; it is instead the name of the chief character — whose life is tracked in the fashion of a bildungsroman. Beginning with vignettes that study him as a five-year-old, then an eight-year-old, Wink’s tale follows August along through his teens and into early manhood. At first, he is found on a dairy farm in northern Michigan, dividing his time between his separated parents; they live in adjacent houses, the father with a girlfriend half his age, his mother a chain-smoking philosophical recluse. There’s lots of potential here for off-kilter drama, but that’s not what comes to pass: August’s child- and teenhood is largely the simple one of most rural places. He grows up helping his father with farm work and spending pastoral days — killing barn cats, catching and gutting trout, watching after-school fights on a dead-end lane, wondering about the girls. There’s a turn in things when his parents actually divorce; his mother takes him to live in Grand Rapids at first, and later, upon receiving a job offer at a library, moves with him to Montana. They settle in Livingston (where Wink lives now, and where many other western writers have been based also), and lead a quotidian life. August grows toward high school, finding a place on the football squad.

9/11 arrives, fixing the story in time — it’s a shock in a small town as everywhere else, but passes. As do most things: virginity is lost to a next door neighbor, a friend of August’s mother… who puts a lid on things; injuries from football cause worrisome headaches, but don’t develop into more. Later, after a classmate who’d enlisted dies in Afghanistan, there is a drunken gathering around a bonfire that ends with a gang rape, but August runs away. Nearing graduation, he opts out of applying to college, and instead leaves home, hitting the road; after a few itinerant jobs, he lands on a ranch. This segment is filled with glimpses of remote Montana: lonely ranchers, rowdy bored neighbors, religious colony isolationists — most of whom tell stories that are variously farfetched, occasionally testing disbelief. It’s a crazy, lost land, but through the bar fights, run-ins with girls, rodeos, accidents with chainsaws and hay balers, August soldiers on, and life continues. The novel winds down with August and his mother heading back to the Michigan homestead where it began, as his father prepares to sell it and move away with his second wife. Somehow it’s all part of the larger picture, if one that can’t be easily explained. Or, as August thinks to himself, “living is just the act of trying to decipher, after the fact, what in the hell had happened.”

A synopsis of Wink’s book may also lead one to wonder what in the hell happened; there is plenty of time and room while reading it to observe that not a great deal does. Initially, you may find the understated nature of this character and his world to be perplexing, possibly dull: drama is portioned out into increments, and many episodes end quietly. But August is funny in a way — over time its small-scale rhythms and monosyllabic reactions generate a comforting beauty that settles in. You develop an ease with its pace, and a curiosity in the ordinary. Montana especially is strongly evoked; I found myself looking up the one-horse towns, rivers, and reservoirs appearing here on Google Maps. In the end, Wink provides some palpable satisfaction, enough so that it’s fair to think that the book is a worthy entry in the tradition, and deserving of the time spent with it.

Drew Hart is from Santa Barbara, California.