Film Interview: Talking to Autumn de Wilde and Anya Taylor-Joy about “Emma.”

By Tim Jackson

A comical version of Jane Austen is coming our way via Autumn de Wilde’s Emma.

Emma., directed by Autumn de Wilde and starring Anya Taylor-Joy. Now screening at the Kendall Square Cinema, AMC Boston Common 19, and other theaters around New England.

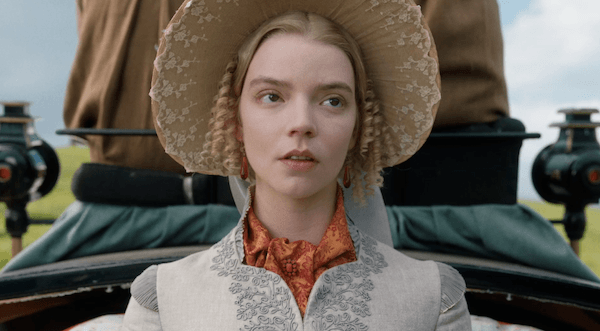

Anya Taylor-Joy as Emma Woodhouse in Emma.

Jane Austen’s novels regularly find their way to the big and small screen, though the adaptations are usually earnest, sometimes lifelessly so. Now a more comical version of Austen arrives via Autumn de Wilde’s Emma. (The title includes a period.) In 1996, a young Gwyneth Paltrow played Emma Woodhouse as a likable busybody. It was followed a year later by Kate Beckinsale in Jane Austen’s Emma. In 2009, a four-episode miniseries produced by BBC and WGBH featured Romola Garai. This year’s Emma is embodied by Anya Taylor-Joy (The Witch, Split) as a not particularly likable heroine who may or may not learn the error of her ways. The actress’s bewitching looks mask the machinations of a pampered busybody and an uncertain young woman. Emma is a devoted matchmaker but, ironically, has much to learn about the vicissitudes of love and of her own heart. The woman’s matchmaking schemes are serious and ludicrous, as are the manners and conventions of Austen’s provincial upper-class families. De Wilde emphasizes the foolishness of it all.

De Wilde, a successful L.A. photographer, has directed some enchanting music videos (Different Names for the Same Thing by Death Cab for Cutie and Rise Up (with Fists) by Jenny Lewis are my favorites). De Wilde has a knack for creating imaginary worlds through a quirky style that is well suited for a playful interpretation of the Austen novel. Emma. is full of stolen glances and painterly landscapes. The sumptuous interiors are crammed full of beautiful tapestries, extravagant portraits, and marble busts. The stunning Yorkshire countryside and its examples of majestic architecture threaten to overwhelm the players; in the same way, Alexandra Byrne’s extravagant period costumes constrain and contain their wearers. The music swings between classical and folk, elements in a lush score by Isobel Waller-Bridge (Fleabag). Cartoonish intertitles comment on the action and identify the players.

I sat with Autumn de Wilde and Anya Taylor-Joy to discuss the adaption of the novel and their collaboration.

On Character:

Anya Taylor-Joy and Autumn de Wilde

Autumn de Wilde: I pitched my version of the film with Anya as part of what I wanted. They had seen my photo work, music videos, and Prada videos. My fantasy cast was part of my pitch — they showed the overall quality I was looking for, and the qualities the characters were going to have. In Anya’s work in The Witch and Thoroughbreds she does this 180 turn like a little clockwork piece. I saw these as complex characters that she did justice to. I thought she was the perfect person to play Emma. We never disagreed, but discussed the character a lot. She is such an iconic character we felt we could keep adding alterations. She’s representative of the human condition, male or female, the “I didn’t mean to hurt” kind of person, someone we all suffer from having to deal with.

Anya Taylor-Joy: Emma’s not a snob so much as she hasn’t been trained to be anything different. When we meet her, she has only been around a very few select people and in a very specific setting. So in the film you’re seeing her first foray into meeting new people and being in the world. She comes to an understanding of her moral code as she goes along.

Collaboration

Taylor-Joy: It’s wonderful to work with directors who pick people who can do the job and trust you to do the job. Autumn doesn’t just cast actors; she casts the heads of departments. These people know what they’re doing, and then she steps back and makes sure everything is going in the right direction. She’s a master collaborator who never makes anybody feel they’re not important on the set, that their opinions aren’t valid. They’d show up during filming and say, “I thought about this and I want to do it this way.”

De Wilde: When people call other artists control freaks, I think it’s very shortsighted. It often means that they are working with people who cannot fulfill the concept that they are putting forward. They don’t have the right people to communicate with. It can also be a dirty word for someone who cares about quality. There is never anything wrong with that.

Music

De Wilde: I love Carl W. Stalling, who did Merrie Melodies, and Disney, too. I also love live-action music, Pollyanna with Haley Mills, and how the music signaled events in an interesting way. I want the orchestra to feel as if it is a character in the film, and close to the actors (even though it wasn’t). Isobel Waller-Bridge, who wrote the score, conveys a natural sense of humor in her music. She is classically trained and understands the tight swing between heartbreak and hilarity. I wanted a Peter and the Wolf [Prokofiev’s symphonic fairy tale for children] strategy regarding character themes. I wondered if it all was going to work together and for me, it really did. The folk music here has such a wonderful way of grounding the emotions, a way of signaling heartbreak.

Cinematography

De Wilde: Barry Lyndon [Kubrick] is, of course, inspirational. I decided when I started directing that I didn’t want to shoot it myself. I like to have a great collaboration with a project’s cinematographer, and Christopher Blauvelt (First Cow, Bling Ring) is a great collaborator. Cinematography is such a solitary task. When I do photography, I like to walk around and take a break. Here I wanted to have a partner and to be the person stepping back to watch.

Acting Emma

Taylor-Joy: I have always been a person who has to feel their own way into a role. Anytime I’ve tried to do something in imitation, because I’ve seen other people do it, it has never felt good or right to me. Regardless of genre or time period, I ask about a character, “Is that person speaking to me, and am I speaking back to them. Can I inhabit their skin?” I always come back to one thing: what is their resting face? What does their face look like when nobody is around, when they’re not being watched? When I can visualize that, they become real people to me. I care about their struggles.

As I understand Emma, if you dive beneath her exterior, she’s very lonely. She’s really only had one true friend — Harriet. Another companion is slightly older, an employee who is being paid to be there. Harriet is like a new puppy to Emma. My feeling was that Emma herself is a puppy, and she’s never had another puppy to play with. So she pretends she knows so much more than Harriet, but she doesn’t really. She knows about rules and how to comport herself, but she doesn’t really know anything more about life. Harriet actually knows something about companionship because she grew up with a bunch of girls. Emma never had that, which is why whenever she walks into the boarding house, it’s like “what are these alien creatures, these rituals they’re performing?” In Harriet, she has found her soul mate. When they break up, it is THE break-up — no offense to Johnny [Flynn, who plays George Knightley, her eventual love interest]. She’s desperate. I think it’s reductive to say Emma only enjoys matchmaking: after all, she only makes one successful match. The only reason she matches Harriet with Mr. Elton is that he is of a class that will raise Harriet to her own class, so Emma will be allowed to be her friend. In the book, she keeps Harriet in the house!

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tim, were you at the advanced screening of Emma at the Coolidge Corner Theater on Tuesday? We were there but did not see you. Dick also saw the Gwyneth Paltrow version and the mini series as well, and he agrees this version was more comical. This portrayal of Emma was more unlikable than the other two versions which was an adjustment for him. I agree that Emma was lonely in a very stuffy upper crust world. I appreciated the audible gasp in the crowd when Emma insulted the older lady at the picnic.

[…] https://artsfuse.org/196808/film-interview-talking-to-autumn-de-wilde-and-anya-taylor-joy-about-emma… […]

I love the movie but Anya is all over the place about Harriet not only in the book but honestly even in the movie she is in. Objectively, Harriet isn’t Emma’s friend at all – that which Austen shows because they don’t really know each other and Harriet would never be Emma’s equal, nor someone Emma considers her equal. There is nothing Harriet does for Emma as a friend. Even when the scene where she confesses loving Mr Knightley is changed compared to the book, for Harriet realizes Emma loves him too here, she becomes arrogant with Emma demanding her to give up aboit her feelings to let her have the guy for herself. I don’t think that’s the moment when Emma really does something wrong. The movie overrates Harriet and is nicer about their relationship than Austen truly is because in the book, Emma actually is glad the girl is too busy with her new husband to be her ‘friend’ anymore. They move on separate ways. Truthfully, Harriet represents Emma’s immaturity and her vain side so making them best friends forever wasn’t at all Austen’s goal. None of the adaptations really get that dynamic.