Poetry Review: Lawrence Joseph’s “A Certain Clarity” — Poetry and Justice

By Ed Meek

Lawrence Joseph makes the case that representing violence in verse is necessary because of poetry’s value as art: to concisely capture these deadly events.

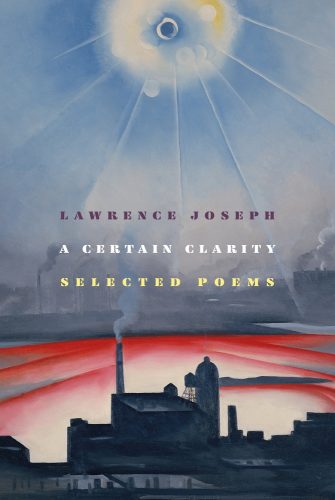

A Certain Clarity: Selected Poems by Lawrence Joseph, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 208 pages, $28.

Born in 1948, Lawrence Joseph writes from a unique perspective. His Catholic Lebanese grandparents emigrated from Syria to Detroit, where he grew up. He became a lawyer and then a professor of law who writes poetry. He synthesizes those elements of his life and career in intense poetry that includes concrete, often violent details, and abstract ideas. For the most part, his vision of the world is dystopian. His poems have echoes of Philip Levine, who also wrote verse about Detroit. Joseph’s poetry, which focuses more intently on language, is more complicated than Levine’s and less dewy-eyed, although not always as powerful. Of course, as a lawyer who writes verse, Joseph is very concerned with the issue of justice.

In his Selected Poems, we can trace Joseph’s development as a poet and see how his verse grows more complex and meaningful both in terms of what he writes about the world we live in today and what he says about the role of poetry in our lives.

“It Will Rain All Day” is from Joseph’s first book, 1983’s Shouting at No One. It begins:

Breakfast at Buck’s Eat Place;

a portrait of Henry Ford,

two eggs, hash browns,

sour coffee. Afterwards

I walk out on Vernor Avenue,

“looks like a river in the rain,”

And later in the same poem:

I pass the bar with “Fight Poverty—

Drink & Dance” scrawled in white paint

across its windowless front,

and then a block-long building,

windows knocked in, wires ripped

from the walls, toilet bowls

covered with dirt and spiderwebs.

It will rain all day.

So, Joseph is a poet who draws on concrete details to recreate a sense of what it was like, for him, to live in Detroit during the 1980s. It is understated but concisely descriptive, leading us to the rain metaphor. Compare this to Levine writing a decade earlier in They Feed They Lion. This is from “Detroit Grease Shop Poem.”

Four bright steel crosses

universal joints, plucked

out of the burlap sack—

“the heart of the drive train”—

the book says, Stars

on Lemon’s wooden palm,

stars that must be capped,

rolled and anointed,

that have their orders

and their commands as he

has his.

Under the blue

hesitant light another day

at Automotive

in the city of dreams.

Levine may identify a little more closely with the working class and he is somewhat sentimental about that attachment. “We’re all there to count / and be counted, Lemon, / Rosie, Eugene, Luis, / and me, too young to know / this is for keeps…” “I am the poet of my city,” Joseph says. Levine would make the same claim. Like Levine, Joseph attempts to record for us his vision of America from the vantage point of Detroit, the city of dreams.

Joseph’s second book, Curriculum Vitae, came out five years later. Here is the first line of “An Awful Lot Was Happening:” “When you come down to particulars everything’s more complicated…” Joseph is expanding the parameters of his poetry; he is using more abstract language to express his responses to life around him. Later, in the same poem, he is back in Detroit:

What was I supposed to do when I heard you could be beaten or worse

in the neighborhood in Detroit between Linwood and Dexter,

the color of your eyes wrong. These are facts.

“There I Am Again” has more echoes of Levine.

Today again, in the third year of unlimited prosperity,

the Sunday night the city burns

I hear sirens, I hear broken glass, I believe…

Today in a place the length of a pig’s snout…

There I am again: always, everywhere…”

One of Levine’s books is entitled Not This Pig: Poems. In it, he writes that “We burn this city every day.” In Joseph’s third book, Before Our Eyes, he explores the role of poetry. In a number of his pieces, he makes use of elevated language and tonal colors. Here’s the beginning of the title poem:

The sky almost transparent, saturated

manganese blue. Windy and cold

a yellow line beside a black line,

the chimney on the roof a yellow line

behind the mountain ash on Horatio.

A circular cut of pink flesh hanging

in the shop. Fish, flattened, copper,

heads chopped off. The point is to bring

depths to the surface, to elevate

sensuous experience into speech

and the social contract…

Joseph is now writing in the early 1990s—the period when academia became obsessed with omphaloskepsis and deconstruction. Later in the same poem:

…but poetry

I know something about. The act of forming

imagined language resisting humiliation.

fading brown and reds, a maroon glow,

sadness and brightness glorified.

Voices over charred embankments, smell

of fire and fat. The pure metamorphic

rush through with senses, just as you said

it would be. The soft, subtle twilight

only the bearer feels, broken into angles,

but kept to oneself. For the time being

let’s just keep to what’s before our eyes.

Joseph here is pushing into the realm of commentary on poetry and how it filters our experience. He’s moving between the abstract and the concrete, almost like John Ashbery, except that he wants to make sense out of the tension rather than skip into the irrational. The last line seems ironic, and casts us back on the content of the poem, as at the end of Robert Frost’s great poem “Directive.” “Here are your waters and your watering place./ Drink and be whole again beyond confusion.” Like Frost, Joseph isn’t saying what he seems to be saying. Instead, both poets are telling us to take another look at what is in their verse.

Joseph’s fourth book, Into It, came out in 2005. In “I Note in a Notebook,” he proclaims, “The technology to abolish truth is now available.” In the poem “Inclined to Speak,” Joseph continues to critique our post 9/11 world.

I saw that. One woman, her personality

and appearance described as lovely,

while performing her predawn prayers,

watched the attackers shoot to death her husband,

her seven-year-old son, three of her brothers,

as they grabbed her four-year-old son from her arms

and cut his throat, taking her and her two sisters

away on horses and raping them. Of course, it’s genocide.

And yes, it brings to mind, Brecht’s point, to write about trees—

implicitly too, to write about pleasure—

in times of killing like these, is a crime;

and Paul Celan’s response, that for Brecht a leaf

is a leaf without a tree, that what kinds of times

are these when a conversation—Celan believed a poem

is a conversation—what kinds of times are these

when a poem is a crime because it includes

what must be made explicit…

the immense enlargement

of our perspectives is confronted

by a reduction in our powers of action…

Joseph is working on a number of levels here. He’s confronting the horrific action which follows a lullaby opening, looking at the violence and then commenting on how the barbarity challenges the role of the poet, how poetry is, as Celan believes, a dialogue between the poet and the audience. He then insists that poetry has a role in our time: to witness, by capturing in words, the violence in our world. Yet, as he says, despite the fact that we now have access to all this information, there isn’t much we can do about it. In fact, we are all, to varying degrees, powerless. Yet Joseph is making the case that expressing these horrors in verse is valuable because of poetry’s value as art: to concisely capture these deadly events.

So Where Are We?, Joseph’s fifth book, came out in 2017. In it, he continues to grapple with the furies of contemporary life. The title poem begins with a reference to 9/11:

So where were we? The fiery

avalanche headed right at us—falling,

flailing bodies in mid-air—

the neighborhood under thick gray powder—

on every screen. I don’t know

where you are, I don’t know what

I’m going to do, I heard a man say;

the man who had spoken was myself…

Asset and credit bubbles

about to burst. Too much consciousness

of too much at once…

Like it or not, a digital you is out there.

It’s complicated, isn’t it? Navigating the world today? Joseph’s poetry distills our puzzlement at a society that is increasingly baffling. We don’t know what we can do about the growing onslaught of violence and irrationality, particularly now, when our country is led by an immoral con man who doesn’t even understand the world around us, but who is influencing it to ill effect.

In a letter to the editor of Poetry in 2005, Joseph asks “Does the existence of the present-day, expanding ‘bureaucracy of poetry’ make it more difficult for genuinely bold and vital poetry to achieve recognition today and in the future?” He writes poetry that is genuinely bold and vital and that deserves a wide audience. There is a long-standing argument in poetry. Does poetry matter? Joseph is making the case through his writing that poetry does indeed matter.

Ed Meek is the author of Spy Pond and What We Love. A collection of his short stories, Luck, came out in May. WBUR’s Cognoscenti featured his poems during National Poetry Month in 2019.