Jazz Preview and Appreciation: Cécile McLorin Salvant Is Coming to Jordan Hall

By Steve Elman

Singer Cécile McLorin Salvant understands that she is heroic.

Singer Cécile McLorin Salvant — one of the greatest experiences your ears can have is hearing one of the smartest jazz singers singing the smartest music.

The late composer and critic Ned Rorem created this formula for The New York Times in 1975: “Singers, like music, fall into two categories — ‘smart’ and ‘dumb.’ [Joan] Sutherland is a dumb singer of dumb music. [Beverly] Sills is a smart singer of dumb music. [Phyllis] Curtin is a smart singer of smart music.”

It’s simple enough to broaden the formula beyond classical singing. We’ve all heard dumb singers singing dumb music. Sometimes dumb singers even try to do smart music, like that of Noël Coward or Stephen Sondheim, with painful results.

But I think Rorem would recognize that the great jazz singers are all smart singers, and the very best of them are among the smartest singers of any music in any genre. By necessity or choice, a lot of them have taken on some very dumb music and made it sound a lot smarter in the process (Example: Billie Holiday singing “What a Little Moonlight Can Do”).

However, one of the greatest experiences your ears can have is hearing one of the smartest jazz singers singing the smartest music. Right now, as I see it, our smartest singer of smart music is Cécile McLorin Salvant. On February 7, she comes to Jordan Hall in a concert sponsored by the Celebrity Series of Boston. If great song interpretation thrills you, and if you do not already have your ticket, do not delay. You must be there.

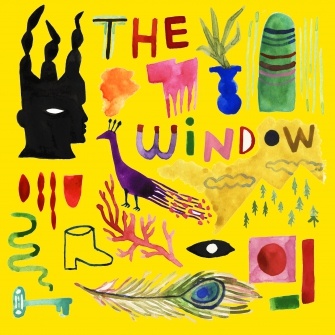

McLorin Salvant (whom I will initialize as CMS from now on) has had a remarkable journey. Her classical study, along with a broad examination of many other genres of music, led to a decision to concentrate on jazz. And then the kudos began: top prize at the Thelonious Monk International Vocals Competition in 2010; Jazz Album of the Year in 2014 from the DownBeat Critics’ Poll for her second CD, WomanChild; Grammy Awards for Best Jazz Vocal Album for each of the CDs she’s recorded after WomanChild (For One to Love, 2016; Dreams and Daggers, 2018, The Window, 2019).

Each step forward in popularity and acclaim seems only to have deepened her commitment to art. She turned 30 last year, but it seems to me that she has already reached a level of artistic maturity that it usually takes a singer many more decades to achieve.

Reviewing all of her recorded work in succession, as I did in preparation for this piece, demonstrates how she has focused and refined her craft, from the early promise of 2010’s Cécile to last year’s glorious The Window. But, good as those CDs are, they cannot prepare you for the experience of hearing her in live performance. I was lucky enough to attend her recital in November last year at Barbican Hall in London, a highlight of the 2019 London Jazz Festival. There were moments during that concert that I was afraid to breathe for fear I would miss something magnificent. Her work that night made me want to open the lockbox of superlatives in search of a new word that could adequately describe what I’d heard.

Obviously, she has perfected the basic elements of vocal performance. She is always on pitch. She always sings the notes she intends to sing. She sings every word clearly. She finds the best songs. She owns their melodies. She stays laser-focused on the message of the words as she sings them. She assembles her programs so that the songs resonate with each other and speak to one another.

Then she digs more deeply. She purges her presentation of anything artificial or extravagant. She conveys the heart of each song as if she has just discovered it. She earns every emotional peak, building to it second by second, putting one great idea after another until that peak is inevitable. When she wants to, she sings substitute melodies with complete conviction. With each new song, she conveys the why behind her decision to sing this particular song . . . and she tells you something important about herself.

I’ll hold further rhapsodizing for the end of this essay, but first, a detour to talk about some examples of ways in which she makes dumb music wonderful and smart music glorious.

It’s hard to think of a dumber song on paper than “The Trolley Song,” written by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane, and given immortality by Judy Garland in the film musical Meet Me in St. Louis (1944, directed by Vincente Minnelli). It has everything (wrong): a hackneyed theme (love at first sight), tediously predictable action, inconsistency for the sake of rhyme (the lovers are seated when they meet and are standing at the end without any explanation), and worst of all, dreadful onomatopoeia (“Clang clang clang went the trolley,” followed by a stupider “Bump bump bump went the brake,” all the way down to an incomprehensible “Pop pop pop went the wheels”). Martin and Blane had one great inspiration, and they saved it for the end, where it has maximum impact — a seven-shot salvo of “and” rhymes that provides the only real reason to sing the tune: “As he started to leave / I took hold of his sleeve / With my hand / And / As if it were planned / He stayed on with me and / It was grand / Just to stand / With his hand / Holding mine / To the end of the line.”

Garland gave this ridiculous ditty a surprising sensuality. Will Friedwald, the great sage of American popular song, praised her performance with a quote from the lyric and a wry comment: “She tells us she ‘knows how it feels / When the universe reels’ (if that’s not a euphemism for an orgasm, I don’t know what is.)”

But that’s not the CMS way. On stage in London, she didn’t need a costume to take on the character of a woman of the 1890s; she did it with tiny inflections that emphasized the prison of convention in which the singer finds herself. She made all the onomatopoeia sound unimportant, inserting pauses that turned the annoying clangs and bumps into background noise for the emotions of her persona. “From the moment I saw him I fell” sounded swoony. “I couldn’t speak because he scared me half to death” sounded agonized and helpless. “When the universe reels” wasn’t about orgasm; it was about a desperate sense of impending loss. “As he started to leave / I took hold of his sleeve” became the triumph of the woman’s courage over social convention. And all those “ands” became a ladder to victory.

By way of contrast, she chose one of the smartest songs for her London encore. It wasn’t one of those flag-wavers that other singers use to knock ’em dead and leave ’em screaming. Instead, CMS sang one of the darkest songs ever written, Kurt Weill’s “The Black Freighter,” known in many versions as “Pirate Jenny,” from The Threepenny Opera, with English lyrics by composer Marc Blitzstein. The singer takes on the persona of a washerwoman named Jenny, portraying her exploitation and abuse at the hands of the men in a “crummy Southern town,” and then giving spectacular free rein to her fantasies of revenge. This is classical repertoire, and CMS didn’t compromise her interpretation by popping it up — or by overplaying the drama. Instead, she reached deep into the story and took the audience deeper and deeper, for a harrowing ride.

There were other choice moments in her London show. She effortlessly turned two smart Bob Dorough songs into a medley, singing the difficult intervals of “Nothing Like You” (which even challenged Dorough in the original recording) flawlessly and editing out the self-indulgent coda he always tacked on to “I’m Hip,” making it even hipper.

At another telling moment, she transfixed the audience with her own keening torch song, “Left Over.” Few singers would risk such desperate words as “Sometimes I wish to hold her near / To press her cheek with gratitude / Saying ‘Thank you for his smile’” and still leave you with pity for the character. Then, immediately after this abject pathos, she restored the balance in her program, calling on Bessie Smith’s repertoire for “Easy Come Easy Go” (“Nothin’ ever worries me . . . I’ll get someone to love me anytime I want.”)

Throughout, it was a joy to hear her interact with Sullivan Fortner, the pianist who worked with her on The Window. He is such a profound player that he deserves many paragraphs, but I’ll simply say that he is gifted with technique comparable to that of Oscar Peterson and grace comparable to that of John Lewis.

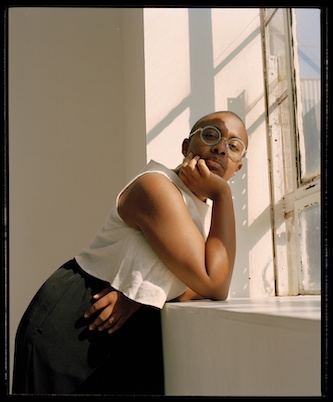

CMS at her most dramatic. Photo: Mark Fitton.

In Boston, the man on the piano bench will be Aaron Diehl, but that is not a reason for disappointment. Diehl is a comprehensive talent on piano, dexterous, powerful, and just as smart as CMS, which is very smart indeed. He also is a player who knows every style of piano; he can conjure any era needed, no matter what the song calls for. And CMS has worked with him longer than she has worked with Fortner, so he knows her whole songbook. The Jordan Hall show will be special for one more reason: since none of the recordings they have made together feature them in this elegant duo format, it will give Bostonians their first taste of their undiluted rapport.

Seeing and hearing CMS is an experience of the first rank. You will be glad you attended this upcoming show, and the memory of her performance will stay with you. But before I let you go to buy your tickets . . .

Cécile McLorin Salvant understands that she is heroic. She knows that she is the youngest in a long line of heroes — Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Betty Carter, Nina Simone, Abbey Lincoln — singers who blazed their own trails, who did what they did because they couldn’t do anything else, people who weren’t capable of compromising their own selves. All of those ghosts are there when CMS sings. She reinvigorates Bessie Smith’s repertoire. She never imitates Holiday, but every once in a while, she draws on a nasal quality that brings Billie back to life. She isn’t as free over the beat as Carter was, but occasionally she strays from the pulse in a manner that is unmistakably Betty. In her writing, she eschews easy structures — not quite in the way Lincoln did, but clearly honoring Abbey’s way.

Ultimately, she transports you from the mundane. She reminds you that love can be bitter, but always redeems. She reminds you that creating is always better than destroying. She reminds you that real heroism is the commitment to defeat the dragons of despair and futility every day. She reminds you that understanding one another is one of the most important responsibilities we have.

Go hear her, and be enlightened.

More:

If you have not yet heard Cécile McLorin Salvant, or if you know only a few of her recordings, here are some remarkable performances from her CDs that you can access via YouTube or Spotify. Whether or not you are in Jordan Hall on February 7, these tracks will show you why she is one of the best singers working today:

Her first two CDs have some fine moments, but these two stand out:

“Moody’s Mood for Love” (from Cécile, self-released, 2010). This song is the quintessential example of vocalese, the weird little subgenre in which a smart singer puts words to a previously recorded jazz solo. In this case, King Pleasure lyricized a James Moody tenor sax solo on the ancient standard, “I’m in the Mood for Love,” building a little drama in which an ardent male tries to talk the object of his affection into loving him, only to find out that she’s already very much in the mood.

Pleasure’s original has been covered many times, and CMS shows real courage in taking it on. First of all, it’s not easy to get around all the twists of what began as an instrumental piece, but she says every word clearly and makes the jumps sound easy. Second, the song calls for the singer to play both the male and female roles, which usually means some falsetto burlesque for the woman’s part; but CMS doesn’t need any jokiness to make both of her characters real, and the woman character has more dignity than she does in any of the other versions I’ve heard. Finally, “Moody’s Mood” tempts the singer to rush things, to get to the point where the woman’s voice comes in, but CMS takes her time and defines the words with tiny elisions and rests. A very smart performance, but not by any means as good as she gets.

“Jitterbug Waltz” (from WomanChild, Mack Avenue, 2013). This is an impossible song, written by Fats Waller as a vehicle for his virtuosity and his impeccable sense of rhythm. It rocks back and forth in a jerky 3/4 time, proving tough even for instrumentalists to play convincingly. Paradoxically, you have to respect its kinks; if you smooth it out too much, it loses its essential character. CMS draws her vocal version from Abbey Lincoln’s book, using clever lyrics written by Charles Green and Maxine Manners. She finds real heart in what is essentially a novelty song, making the most of the scenario, with two dancers almost too tired to continue . . . and yet sparked by their love to stay out on the floor. Does CMS have a little too much fun with it in her last chorus? Maybe, but she makes everything right in the way she sings the last lines (“You’d stay up half the night with me if I would let you / So come, let the waltz play again”).

Her third CD shows real confidence, and has many gems, including a version of “The Trolley Song.” Here are three more:

“Wives and Lovers” (from For One to Love, Mack Avenue, 2015). If one performance could be said to have “made” Cécile McLorin Salvant, it’s this one. The original song was a gigantic misstep for the veteran song team of Burt Bacharach and Hal David, so misogynistic that it actually offended some mainstream listeners when slick crooner Jack Jones (talk about dumb singers . . .) had a huge hit with it in 1963. It purports to be advice to the “typical” suburban housewife about her duty to be attractive to her hard-working husband, but it manages to turn both woman and man into pathetic objects. Why would a smart singer even consider such a tune? Listen and be amazed. Suddenly, the “advice” is barbed with menace, as if the singer of the song is not some patronizing man, but the sophisticated Other Woman who can’t wait to get the husband away from his one-dimensional wife — and that’s just the beginning of the richness here. This is one of CMS’s great triumphs, and a performance that earned her broad recognition.

Dreams & Daggers cover art.

“Growlin’ Dan” (from For One to Love, Mack Avenue, 2015). This is a tune associated with Blanche Calloway, so by reviving it, CMS casts a bit of limelight on Cab Calloway’s lesser-known sister. But it isn’t a nostalgic look back; if anything, CMS gives it a freshness that shows reverence for the ebullience of the swing era. The title and CMS’s singing provide a great musical pun — the eponymous “Dan” is a master of the style called “growl trumpet” back in the day, so CMS draws on her own vocal growls to pay it off. Only with a lot of care and discipline could a singer create a performance that feels so free.

“Stepsister’s Lament” (from For One to Love, Mack Avenue, 2015). What, the song from Cinderella? The one that’s supposed to provide a bit of sympathy for the heroine’s “ugly” siblings? Yes, and behold the definitive version of a Rodgers and Hammerstein tune that needed a champion. It’s supposed to be comic, and CMS gives it a smile, but along the way she makes it into an anthem for all the supposedly plain girls who get outshone by the Homecoming Queens and Miss Universes of the world.

Her fourth CD, a two-disc set, threw down the gauntlet from its very cover: this is Serious Time. Mark Fitton’s cover photo was surreal and enigmatically symbolic: a stark floor of black and white tiles, its regularity broken by a piece of an orange pile carpet; over this background, CMS’s arm jutting powerfully at a sharp angle, her hand holding a circular mirror; in that glass, part of her face reflected, with one eye shaded white, the other shaded close to her natural skin tone. The substance of the CD was just as serious — a luminescent set of live recordings juxtaposed with a group of her own poetic compositions recorded in a studio with a small string section. Such ambition could have been a grand miscalculation, an overreach for an artist getting too arty. But the result is as rich as its promise, with a great selection of tunes by composers as diverse as wise-guy Bob Dorough and super-serious Kurt Weill. It’s shot through with great performances, from which three stand out to me:

“Never Will I Marry” (from Dreams & Daggers, Mack Avenue, 2017). This Frank Loesser song was written for a male singer in the 1960 musical Greenwillow but, when Barbra Streisand recorded it in 1964, it sounded like an independent woman’s rejection of the sterile world portrayed in “Wives and Lovers” from the previous year. Streisand made it into a mini-aria. CMS takes a lighter touch, and turns it into a swinging romp, showing off her chops and suggesting that the singer doesn’t really reject men — the girl just wants to have fun.

“Somehow I Never Could Believe” (from Dreams & Daggers, Mack Avenue, 2017). Kurt Weill’s music, with a lyric by Langston Hughes, from the opera Street Scene (1946). Here are all the great themes that CMS likes to explore – the loneliness of life, dreams deferred, woman striving, class injustice, a yearning for a better tomorrow — in a single exquisite package. And she is magnificent throughout, using her upper and lower registers and all her “characters” — opera singer, child, Pollyanna, world-weary woman — to illuminate every word. Aaron Diehl’s kaleidoscopic arrangement is perfect.

“I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” (from Dreams & Daggers, Mack Avenue, 2017). Here’s a Richard Rodgers – Lorenz Hart tune that CMS loves. Like many other tunes she favors, this one has a twist at the end. The persona is so dizzy with love that she can’t even look at her watch but, in the last line, she says she’s finally got her feet on the ground (“I’m wise and I know what time it is now”). CMS has recorded it twice — this live version comes four years after the first go-round, on WomanChild. (I also heard her sing it in London.) The clever arrangement — probably Aaron Diehl’s idea — inserts little stop-time effects into the last chorus that point up the words. This version tops the original because CMS sings an alternate melody in that last chorus and makes it completely her own.

Aaron Diehl’s playing has all the elegance of his photographic persona, plus a lot of style and swagger. Photo: NEA.

Her most recent CD foreshadows the current tour — it was a set of duo performances with Sullivan Fortner, some recorded live. There are too many great moments to catalog here, but I’ll just point to two:

“I’ve Got Your Number” (from The Window, Mack Avenue, 2019). This bouncy, confident tune is from Cy Coleman, a composer CMS has been exploring recently. (She sang two lesser-known Coleman tunes, “You Fascinate Me So” and “With Every Breath I Take” in London, and we can hope for her to do them again when she comes to Boston.) The lyric here (by Carolyn Leigh) isn’t quite predictable — the singer starts by taking the object of her affection down a peg or two, but gradually reveals that she’s just as vulnerable as he is — so “why should we not combine?” CMS sings this with such lovely forward motion that you think you know just where it’s going, only to be delightfully surprised by the way she adds nuance to every line.

“The Peacocks” (from The Window, Mack Avenue, 2019). This is the ringer on the CD — the only tune where the CMS-Fortner duo is augmented by a third player, the bright and talented Argentinian tenor saxophonist Melissa Aldana. Pianist Jimmy Rowles wrote the music, and singer-poet Norma Winstone put words to Rowles’s melody, creating a reverie of suspended animation that justifies the alternate title it’s often given — “A Timeless Place.” Winstone’s poetry (as I’ve noted in a previous post) has returned again and again to a theme she explores beautifully here (“Beauty’s only an illusion . . . a mirage is all it’s ever been”) and CMS gives the lyric a supremely sensitive interpretation. Ultimately, even as she recognizes the evanescence of existence, Winstone is positive, and her advice to the listener is the essential message of almost everything Cécile McLorin Salvant sings: “Find a quiet place inside / Where you can listen to the things your heart is saying.”

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Great piece. I cannot wait to see her next month.

This is an excellent, cogent survey of Ms Savant’s work. She is certainly deserving of your elloquent praise. I have seen her in performance and she is thrilling on a par of an operatic diva, hence your insightful introduction. (Mr Diehl is my favored accompanist, having seen him perform many times.)