Visual Arts Review: The National Academy of Design — Another New Chapter?

By Peter Walsh

This fascinating exhibition surveys the entire history of the National Academy membership and, almost incidentally, provides a potent cross-section of the history of American art and its discontents.

For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design on view at the New Britain Museum of American Art, 56 Lexington Street, New Britain, CT through January 26.

William Merritt Chase, The Young Orphan, n.d., oil on canvas. National Academy Museum, New York.

Just what is American art, anyway? If you were an artist in the early American Republic, the answer was far from clear.

For the first generations after the Revolution, the American art infrastructure was very thin. The leading art patrons of Europe—royalty, aristocracy, and the Catholic Church—weren’t available. In Calvinist early America, lavish displays of wealth were frowned upon, and church decorations were banned. There were no art schools, no public art museums, and the few, scattered colleges were provincial, small, and mediocre. Art wasn’t on the curriculum.

For working artists, things were tough. Painters, often self-taught, made an itinerant living, moving from place to place with the market, making portraits of prosperous merchants, craftsmen, and scholars, and occasional murals. The most accomplished painters—John Singleton Copley, Benjamin West, Washington Allston—were drawn, almost inevitably, to Europe for training and patrons. Some never returned.

Few artists were more frustrated by this situation than Samuel F. B. Morse, known to generations as the inventor of the telegraph and Morse code. Now that those inventions are fading from collective memory, Morse is increasingly remembered for his earlier reputation, as the leading American portrait painter of his generation. Aware of the elaborate institutions that supported artists in Europe, in 1811, Morse traveled to England with the young Allston to study with West, and later at the Royal Academy. He spent three years in Europe.

Back in the United States, Morse painted leading figures of the Revolution and early Republic, including Presidents John Adams and James Monroe and the Marquis de Lafayette. But, despite his best efforts, financial success eluded him. He remained deeply frustrated by his country’s unprofessional and provincial art institutions, especially New York’s stuffy and unsympathetic American Academy of Fine Arts, controlled by politicians, businessmen, lawyers, doctors, and the tyrannical John Trumbull, the aging “Painter of the Revolution,” who served as its president.

Morse and a small group of like-minded students broke off to form an alternative branch, modeled on his experience with the Royal Academy. Efforts to reconcile with the American Academy failed, and eventually, in 1825, Morse and his friends formed a new institution that came to be known as the National Academy of Design. The American Academy folded in 1841 but the National Academy survives to this day.

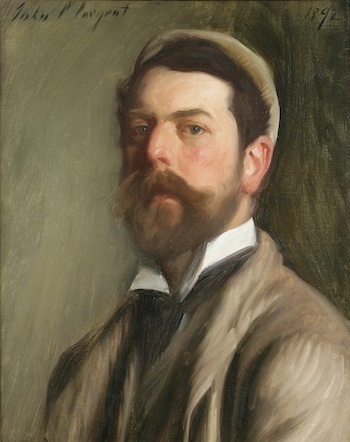

John Singer Sargent, Self-Portrait, 1892. National Academy Museum, New York.

A fascinating exhibition organized by the present-day institution, For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design, on view at the New Britain Museum of American Art, surveys the entire history of the National Academy membership and, almost incidentally, provides a potent cross-section of the history of American art and its discontents.

Those artists invited to join the Academy, many of them former students there, were asked to submit a characteristic work for its collections and, up until 1994, a self-portrait or portrait painted by a fellow artist. The exhibition is drawn from the submissions of a selection of the Academy’s many members since Morse’s day.

Things begin grandly, with works by the leading American painters of the early 19th century: Morse, John Frederick Kenneth, Asher B. Durand, Albert Bierstadt, Frederick Church, Eastman Johnson, and Winslow Homer. Many of these were part of the group of landscape painters known as the Hudson River School, the first to paint in a truly American idiom. Highlights include Morse’s dignified portrait of his teacher, Benjamin West, painted about 1811 during his stay in England; his own early self-portrait (about 1809); Kensett’s The Bish Bash (1855), a study of a lively waterfall in the woods near the Massachusetts border; Bierstadt’s grand and moody Wyoming landscape On the Sweetwater near Devil’s Gate (1850;, and Church’s panoramic Scene among the Andes (1854), from the artist’s South American sojourn. Homer’s Croquet Player (about 1865) and George Inness’s Landscape (1855) hint, with their undramatic, domesticated scenery and off-center compositions, at the aesthetic changes soon to appear in American painting.

The Hudson River School already seemed old fashioned to the painters of the Gilded Age, hung a gallery away. Both the artists and their American collectors were now traveling regularly to Europe, where they picked up fresh ideas of Realism and Impressionism. Painted when artists were reaping the benefits of a booming economy and an increasingly sophisticated group of wealthy art collectors, many of whom were artists and even Academy members themselves, many of these works celebrate wealth, fashion, and cultivated leisure. It is as if the smoke, dirt, and poor immigrant workers of the post-Civil War industrial revolution were confined to another continent.

John Singer Sargent’s dashing Self-Portrait (1892) shares space with William Merritt Chase’s languid young female model in The Young Orphan [or] An Idle Moment [or] Portrait (1884). She is a real orphan Chase found in an asylum, but her pose, red velvet chair, luxurious hair, and classical features could easily be those of a millionaire’s daughter, a more common Chase subject. The soft-focus pastels of Frederick Carl Frieseke’s Hollyhocks (by 1911) and Childe Hassam’s The Jewel Box, Old Lyme (1906) suggest the influence of the French Impressionists, by now increasingly popular with American collectors, on the so-called “American Impressionists,” who avoided the shocking subject matter and social commentary of their French namesakes. Sargent’s Claude Monet (1887) shows how Americans were now being accepted on the wider stage of world art. Robert Frederick Blum’s mildly satirical Two Idlers (1885-89) barely hints at the coming storms of the 20th century.

In 1913, the watershed “Armory Show” opened in New York City’s vast 69th Regiment Armory. Organized by a group of American artists who wanted to broaden perspectives and opportunities for American art, the show, which included some 1300 paintings, sculptures, and decorative arts by over 300 American and European modern artists, was a major succès de scandale. It drew huge crowds and outraged comments about “insanity” and “quackery,” particularly for the Fauve and Cubist works in the show, which had never before been seen in public in the United States. President Theodore Roosevelt exclaimed “That’s not art!” When the show moved on to Chicago, the uproar reached the state government in Springfield, where the legislature’s “white slavery commission” threatened to investigate the “many indecent canvasses and sculptures” on display.

Andrew Wyeth, Self-Portrait, 1945, oil on canvas. National Academy Museum, New York.

The Armory Show was considered a direct confrontation to the National Academy of Design and its ideas about American art. It touched off a fierce, if now largely forgotten, civil war in the American art world that raged for decades. Often tinted by American nationalism and xenophobia, attitudes toward the alternate world of what is now considered early American modernism continued to be hostile. Prominent New York art critic and antimodernist Royal Cortissoz lumped all the immigrant trends together as “Ellis Island Art.” Huntington Hartford, art patron, collector, and heir to the A & P fortune, decried “the ice age of art” that was freezing out the great traditions of painting and sculpture: the “beatnik, the Existentialist, the juvenile delinquent, the zaniest of abstract art, the weirdest aberrations of the mentally unbalanced, the do-nothing philosophy of Zen Buddhism” that, for him, the new American art came to represent.

That civil war is largely off-stage in the remaining galleries of the New Britain exhibition. At first, the artists on view still represent what most Americans considered at the time to be the mainstream of American art: Robert Henri, N.C. and Andrew Wyeth, Reginald Marsh, George Bellows, John Steuart Curry. But, increasingly, the artists not represented become as significant as those on view: no Georgia O’Keeffe, no Marsden Hartley, no Stuart Davis, no John Marin — all those who embraced, in different ways, the new “isms” out of Europe.

Robert Frederick Blum, Two Idlers, 1888-89, oil on canvas. National Academy Museum, New York.

In 1942, the National Academy moved to a fortress-like granite mansion donated by philanthropist Archer M. Huntington, far up Fifth Avenue at 89th Street, well north of the the original locations of rising new art institutions further downtown—like the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and the Guggenheim—which embraced very different ideas about what American art could and should be. The focus of the Academy had also shifted from New York, where avant-garde art was becoming dominant, to a more conservative national membership that not only embraced regional artists and art centers but also included increasing numbers of women, African Americans, and other minorities.

Not long after, postwar American art triumphed on the world stage. New York City became the undisputed center of the art world. What better result could Morse have imagined back in 1825? Yet the artists that above others created that victory—Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Andy Warhol, artists who had finally broken free of European art and created a truly American school—are nowhere to be found in these later galleries. Though there are important artists and much of interest to be seen from the postwar decades, the art in the New Britain show remains resolutely representational, avoiding abstraction and most of the foreign isms to the very end.

Over the almost two centuries of its life, the National Academy of Design had gone from being the dominant art institution of New York to being one of the most obscure. Yet life went on up in the refuge at 89th Street, sometimes rocked by the administrative upheavals and controversies that have disrupted other older cultural institutions in the city. This exhibition is a bid, perhaps, to open yet another new chapter.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than eighty projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.

Tagged: For America: Paintings from the National Academy of Design, National Academy of Design