Visual Arts Review: The Legacy Museum — An American Inheritance

By Kathleen Stone

The Legacy Museum draws on a passionate and visceral mix of architecture, graphics, text, art, music, video, and spoken word to prove that — ever since the time of slavery — white views on race have distorted the presumed fairness of our legal system.

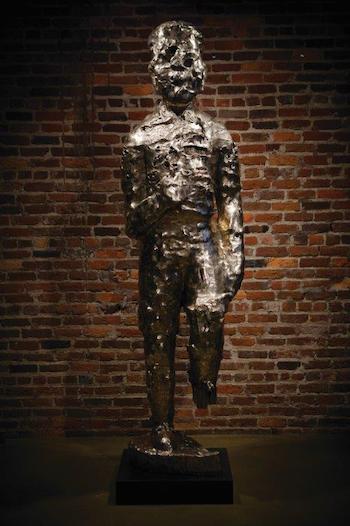

“Doubt” by Titus Kaphar. Photo: Equal Justice Initiative/Human Pictures.

The story starts on the outside of the building. Photographs, large and color saturated, cover The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration’s façade. In one corner is a group of enslaved persons; opposite is a lineup of young black men wearing orange jumpsuits. Between these images are pictures of a slave auction, a public lynching, a fire hose spewing water at a black body. Also a woman’s hands, resting gently on a man’s shoulder. The color photos express the narrative at the museum’s core: the end of slavery gave way to prison labor, lynchings, and segregation. Which led to the misery of today’s mass incarceration.

Inside the museum the story is taken up again, beginning with a lesson about the slave trade as it existed in the 1800s. In a dim room, set against black walls, small red lights pulse against a map of the United States; the lights mark the routes along which persons were trafficked after 1808. That year an international ban on transatlantic trafficking was enacted and traders – theoretically banned from new imports of enslaved human beings – moved those already in the country from the mid-Atlantic into the deep South. The dots blink most ferociously around Montgomery, Alabama — it was the epicenter of the domestic slave trade. Also, by 1860, home to the fledgling Confederacy.

It is no coincidence that the Legacy Museum was built in Montgomery and in a building that once warehoused human beings. The museum and its companion, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (often referred to as the “lynching memorial”), are the work of the Equal Justice Initiative, a legal services organization led by attorney Bryan Stevenson. When he began the EJI, Stevenson’s primary mission was to represent inmates on death row. Alabama not only has the death penalty but the state boasts the highest rate of execution per capita in the country. In the 30 years since its founding, EJI has expanded its portfolio of cases, but the museum and the memorial, both opened in 2018, quickly catapulted EJI into the national conversation about criminal justice.

As with any well-prepared legal case, the museum draws on evidence to persuade. But, unlike courtroom proceedings, where rules of logic govern what evidence is admitted, it draws on a passionate and visceral mix of architecture, graphics, text, art, music, video, and spoken word to prove that — ever since the time of slavery — white views on race have distorted the presumed fairness of our legal system.

From the room with the red dotted map, a ramp descends to a lower level where the bulk of the museum’s exhibits are located. On the way down, next to the ramp, sit jail cells where holograms project images of captured slaves. A soundtrack gives us the words of the incarcerated: the most haunting are pleas of the imprisoned to see their families again.

The walls of one of the large rooms at the center of the museum are covered with black-and-white photographs. One is of Private Gordon, an enslaved black man who fled to the safety of a Union Army camp in 1863. The jagged ridges on his naked back, the residue of repeated whippings, resemble the mountains on the papier-mâché maps children make in school. Another photo displays emaciated men on a British ship who had been rescued from East African slave traders, 60 years after the supposed ban on transatlantic trafficking. A 1919 photo is testament to a public lynching, the result of releasing a black man awaiting trial to a mob. The governor claimed he was powerless to stop what happened next. Ten thousand people gathered, as though at a carnival, to watch and cheer as the man was hanged, shot, and burned.

The next room features signs. They announce auctions and offer rewards for runaways, texts that include precise details about the persons to be sold or recaptured, including names, identifying marks, and locations where last seen. The black letters on white (though sometimes the ghostly reverse) are stark in their graphic simplicity. As I stand in front of the signs taking notes, an African American woman approaches me and asks for a piece of paper. “I think I’ve just found my family,” she says.

The 19th century gives way to the 20th, and more photographs. Prison laborers. Lynchings. Ozie Powell, one of the so-called “Scottsboro Boys,” hunched over in a courtroom seat. A convict strapped into an electric chair.

Two strands of color intrude into the black-and-white motif of these rooms. One is a set of shelves with glass jars filled with powders that look like turmeric, cardamom, and oregano. But no. This is dirt, from red clay to black alluvial silt, gathered from lynching sites, earthy reminders of crimes in the American landscape. The second bolt of color comes from a statue titled Doubt, by artist Titus Kaphar. His statue presents a black man clutching a piece of fabric with colors, ranging from luminous gold to sea foam green, blood red to ocean blue, that fade to rusty brown. It’s a vision of anguish grasping at hope. Or maybe at an illusion of hope.

More recent history comes next. There is the 1957 photo of Elizabeth Eckford, then a teenager, standing outside Little Rock’s Central High School. On the first day of what was supposed to be an integrated school year, she was greeted by white students screaming and the Arkansas National Guard blocking her path. Nearby, an audio track plays a male voice ranting: “I don’t want Negroes to control the making of laws that control me. I would feel better if all Negroes were removed from the voting rolls.” This is the voice of Tom Brady, a judge on the Mississippi Supreme Court, also a member of a white Citizen Council formed to resist desegregation in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. Then there’s another voice, this one shouting: “Segregation now. Segregation tomorrow. Segregation Forever.”

“BAM (for Michael)” by Sanford Biggers. Photo: Equal Justice Initiative/Human Pictures

These are the words of George Wallace, being inaugurated as Alabama’s governor in 1963. He presided in that position from the state Capitol building, situated at one end of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue, the main thoroughfare that cuts through the city. Next to the Capitol, on the rear lawn, is a large Confederate memorial, its cornerstone laid by Jefferson Davis himself, in 1888. At the other end of Dexter Avenue is Court Square, site of the 19th-century slave market. Between these stark reminders of Montgomery’s history stands the Alabama Judicial Building, home of the state Supreme Court. Here former Chief Justice (and current candidate for the U.S. Senate) Roy Moore installed a monument engraved with the Ten Commandments. The monument is gone now, but if you were to visit the chambers of the present Chief Justice, you will see Biblical scripture on the wall: “But let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

The Alabama Supreme Court devotes a significant amount of its time to death penalty cases. Lawyers in those cases have 30 minutes to address the court, instead of the usual 15. “We take these cases seriously,” one judge tells me during my recent visit. “You must have confidence in the system to impose a penalty so final,” I say. “Yes,” he answers, “we do.”

EJI’s website is filled with information about the death penalty. In Alabama, a jury’s death verdict need not be unanimous. Until recently, a judge had the power to impose the death penalty, even when the jury voted merely to imprison. Regarding the possible permutations of victim and defendant, the most lethal combination, statistically, is a black defendant and a white victim. For an outsider, such facts tend to undermine confidence in the system.

The museum’s display of legal texts makes clear that throughout American history federal and state courts have been complicit in upholding and perpetuating slavery and segregation. Among the country’s most notorious cases is one that involved a man named Dred Scott. In 1857, the United States Supreme Court denied Scott’s petition to be freed from slavery. According to Chief Justice Taney, who wrote for the majority of the court, blacks, even if they were born in this country, were not entitled to the privileges of citizenship because blacks were a “subordinate and inferior class of beings.” Forty years later, the Supreme Court decided another infamous case, this one involving Homer Plessy, a passenger on a train in Louisiana. Because he was of mixed race, Mr. Plessy was assigned to sit in the “colored” car. When he challenged the state law that segregated passengers according to race, the U.S. Supreme Court found that nothing in the federal Constitution prevented segregation.

A flood of restrictive legal codes ensued, from the late 19th into the 20th century. In Alabama, for instance, white female nurses were prohibited from tending to black male patients. Businesses open to the public had to maintain separate entrances. In restaurants, black and white patrons were physically separated: walls were required to be seven feet high or more. Racially mixed groups were forbidden to play games of cards, dice, dominoes, or checkers.

And today? Here the museum pulls no punches. Civics classes teach that every defendant is presumed innocent until proven guilty. But, in words printed on the wall, the museum asserts that this presumption of innocence does not apply to African Americans. To the contrary, they are presumed to be guilty and dangerous, and that often leads to an unfair administration of criminal justice. In truth, lawyers, judges, and criminologists examine a number of different factors that lead to crime and incarceration, including such nonracial factors as poverty. But the Legacy Museum forces viewers to acknowledge that race has indeed played a major part in shaping our beliefs, laws, and actions.

In the final corridor walls are hung with artwork. Facts give way to artistic epiphany. A linoleum print by Margaret Burroughs, Cotton Pickers in Texas, shows farm hands dragging long bags stuffed with cotton through the fields. Contemporary Cubicle, a drawing by James C. McMillan, depicts a man’s body compressed within a cube – an acute image of physical and psychological claustrophobia. In BAM (for Michael) a bronze male figure is seen taking apparently strong and vigorous strides. But that’s not so. This is a tribute to Michael Brown, after all. Artist Sanford Biggers sculpted the figure in wax, shot the work up with bullets, and then recreated it in metal. What should have been a healthy young man is a mortally wounded body, preserved in bronze.

At the door is a compilation of videos. Andra Day sings a haunting rendition of “Strange Fruit.” Lil Buck and Jon Boogz dance the roles of inmates in Am I a Man. Alvin Ailey’s troupe performs to Wade in the Water, the performers embracing the fluidity of emotion. The color, sound, and movement of these final videos provide an exhilarating release from the stark exhibits that have come before.

Much of what one sees in the Legacy Museum – vintage photographs, signs, legal codes, court decisions – is black-and-white. This dual color scheme makes for striking graphics, but it also conveys the continuing weight of our country’s racial history. It reminds viewers that this legacy has been inherited by us all. And it suggests that, if we are to make a future together, we must understand our shared, twisted history.

Kathleen Stone lives in Boston and writes critical reviews for The Arts Fuse. She co-hosts a literary salon known as Booklab and is at work on several long projects. She holds graduate degrees from the Bennington Writing Seminars and Boston University School of Law, and her website can be found here.

I’ve been to the The Legacy Museum twice and found it, of course, profound and moving. I’m incorporating my visit into a short story and in working on it have read a number of reviews. This is a very difficult and complex subject for any writer, particularly a white writer (in my opinion). Your review is by far the most sensitive and thoughtfully drafted. Well done. And thank you.