Classical Album Review: A Splendid Introduction to the Music of Alberto Ginastera

By Susan Miron

Alberto Ginastera’s innovative style often draws comparisons to Bartók and Stravinsky for the artful ways in which he integrated folk music and dance forms from his native country into a striking, modernist musical language.

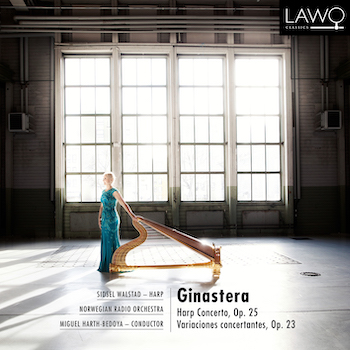

Norwegian harpist Sidsel Walstad. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

During her 16 years as harpist of the Philadelphia Orchestra (1930–46), Edna Phillips (its first female member) commissioned many pieces for harp, but none came close to achieving the success of the Ginastera Harp Concerto. Ms. Phillips (my harp teacher during college) and her husband Sam Rosenbaum became quite frustrated at the time it took Alberto Ginastera (1916–1983) to complete this concerto. She told interested parties, “After Ginastera accepted our commission in 1956, we hoped it would be ready for the American Music festival in Washington, D.C. But, as we neared that date, I started getting letters from him in Argentina telling me about problems with Perón and his troubles with an opera he was writing and other difficulties. The harp concerto kept getting put off. It took forever, but what a triumph it turned out to be.” Note: Ginastera preferred the European pronunciation with a soft “g”- as in giraffe. Ginastera is a village in Catalonia, Spain, where the composer’s family lived before migrating to Argentina. This is how their name is pronounced in Catalonia.

During the time the harp concerto was on his desk, Ginastera was also working on the opera Phillips mentioned, along with his Piano Concerto No. 1, Violin Concerto, String Quartet No. 1, Piano Quintet, and Cantata para América mágica. Composed between 1956 and 1964, the Harp Concerto was premiered by harpist Nicanor Zabaleta with the Philadelphia Orchestra. It eventually became, by far, the most popular harp concerto of the 20th century. The piece sizzles with color, partly because of its enormous battery of percussion instruments: bass drum, bongo drums, claves, cowbells, crotales, glockenspiel, güiro, maracas, small triangle, snare drum, suspended cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, tenor drum, tom-toms, triangle, whip, wood block, and xylophone. Of course, credit must also go to the piece’s sustained moments of beauty and drama, melting lyricism, and ingenious sound effects (glissandos played with the nails, drumming on the soundboard, whistling sounds made by moving the palm upwards on the wire strings, pedal slides). As if that were not enough, there’s a stunningly long cadenza that moves into the thrilling third movement, which the harp, quite unusually, commands, stating melodies that are copied by the orchestra. The first movement features a vigorous Argentinian dance, a malambo, associated with gauchos, alternating 6/8 time with 3/4; the second movement will remind listeners of a Bartók night scene.

Ginastera’s innovative style often draws comparisons to the latter composer and Stravinsky because of the artful ways in which he integrated folk music and dance forms from his native country into a strikingly modernist musical language. Ginastera’s concerto has become standard fare in international harp competitions; in fact, most harpists use it in competitions against other instrumentalists who draw on more impressive, if standard, repertoires. And they often win. It’s that effective, that spectacular.

This new disc devotes itself to two of Ginastera’s well known pieces, the Harp Concerto and Variaciones concertantes. Norwegian harpist Sidsel Walstad performs the Harp Concerto well, though, oddly, she sounds considerably better on the composer’s Variaciones

This new disc devotes itself to two of Ginastera’s well known pieces, the Harp Concerto and Variaciones concertantes. Norwegian harpist Sidsel Walstad performs the Harp Concerto well, though, oddly, she sounds considerably better on the composer’s Variaciones

Variaciones concertantes was composed in 1953, during a difficult period for Ginastera because political conflicts with the Perón government forced him to resign as director of the music conservatory at the National University of La Plata. He supported himself by scoring films, as he had been since 1942, and accepting commissions such as the Variaciones, which came to him from the Asociación Amigos de la Música in Buenos Aires, where Igor Markevitch conducted the work’s premiere in June 1953. It has became recognized as a central work in Ginastera’s second stylistic period (“subjective nationalism”), an approach in which folkloric and traditional materials are idealized and sublimated in a personal way. One characteristic musical strategy: its harmony is derived from the open strings of the guitar, as heard in the harp under the solo cello statement of the theme at the piece’s beginning — and again, before the final variation. (These pitches – E, A, D, G, B, E – also supply material for the work’s variations and represent the main key areas for the entire composition.) Two interludes (the first for strings, the second for winds) are used to frame seven variations that spotlight different solo instruments with the orchestra — flute, clarinet, viola, oboe and bassoon, trumpet and trombone, violin, and horn.

Ginastera rounds this off with a reprise of the main theme, again accompanied by the harp, but this time with double bass taking up the melody. A final variation, for the full ensemble, is an ebullient malambo, the kind of gaucho-inspired dance that was a comforting staple for Ginastera. The steadily repeated notes represent tapping feet, which seem to welcome the arrival of virtuosic and jazzy instrumental flourishes. This CD is a splendid introduction to a gifted composer.

Susan Miron, a harpist, has been a book reviewer for over 30 years for a large variety of literary publications and newspapers. Her fields of expertise were East and Central European, Irish, and Israeli literature. Susan covers classical music for The Arts Fuse and The Boston Musical Intelligencer.

Tagged: Alberto Ginastera, Ginastera Harp Concerto, LAWO Classics, Norwegian Radio Orchestra, Sidsel Walstad