Film Review: “Parasite” — Notes from the Underclass Underground

By Neil Giordano

Parasite’s powerful vision of the existentially downtrodden offers equal nods to Karl Marx and Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

Parasite, directed by Bong Joon-ho. Screening at Coolidge Corner Theatre, Landmark Kendall Square Cinema, and AMC Boston Common.

Park So Dam and Choi Woo Shik in “Parasite.”

Rarely has there been a cast of characters as simultaneously loathsome and endearing as those in Bong Joon-ho’s quasi-satirical Parasite, which manages quite a hat trick. It is a laugh-out-loud comedy, a compelling tale of intrigue and deception, and a humane examination of the inequities of social class. (It also won this year’s Palm D’Or at Cannes.) Given that Parasite borders at times on farce, you might expect broad caricatures of the greedy rich and the bedeviled poor. But no, Bong is not interested in easy answers. He gives us two sympathetic families on opposing sides of the class divide — and neither group can be easily pigeonholed.

The protagonists, the Kims, struggle to make ends meet, living below street-level in a Seoul neighborhood where their daily entertainment includes chasing away a drunk who urinates outside their window. They can’t pay their cell phone bills, so they are forced to acrobatically contort phone-laden arms in order to scrounge WiFi from the neighbors. At one point, the Kims scrape together some easy cash by folding pizza boxes for a corporate chain. But a pizza company rep doesn’t like the quality of their work and warns them “We can always get someone else.” They represent the desperate underclass, struggling to survive in a cold capitalist society. Stable, well-paying jobs are always out of reach. Yet the Kims are not completely salt-of-the-earth: they are flawed and fallible figures, far from liberal emblems of the noble or despairing poor. Kim Ki-taek, the father, is an unemployed chauffeur; he wards off the family’s shabbiness with good humor and works at keeping the peace. His two twenty-something children, Ki-woo and Ki-jeong, are determined to escape their underground existence. All they need is an opportunity. . . .

Enter the Parks, spiritually and materially the inverse of the Kims. The Parks are a Gangnam-style Ozzie and Harriet, lovely beings who have lots of money to spend. Mr. Park is a handsome tech pro, Mrs. Park a status-conscious but well-meaning stay-at-home mom. She watches over their two children, the beautiful and amiable teenager Da-hye and young Da-song who, wearing a feathered headdress, enjoys shooting toy arrows at people. They live in a sumptuous house right out of Architectural Digest (literally). They lack for nothing because of the large paychecks Mr. Park brings home.

These are not evil people. If this is an eat-the-rich satire, as the title implies, the Parks do not deserve to be chewed up. They are “nice,” a word uttered often in their favor so that we will not dislike them. Yet they are also flawed, and betray an ominous unease with their lives. Mr. Park revels in playing with his son, but the odd boy has a damaged past (revelation of which is a major plot point). Likewise, Mr. Park adores his wife but he cannot quite admit he’s in love with her. But this family’s flaws can be smoothed over with money, as Mrs. Kim pithily observes. The Parks’ big bank account gives them the material comforts necessary to ignore or bury their underlying personal problems.

The plot is set in motion when Ki-woo, with the help of sister’s forgery skills, finagles his way into the Park household as a tutor to Da-hye. Soon, the Kims’ trickery brings in Ki-jeong as an “art therapist” for Da-song — without anyone knowing they are brother and sister. The real fun begins when Mr. and Mrs. Kim join the staff as driver and housekeeper. All four serve their respective Park counterparts, each assumes a fraudulent identity along with a manufactured personality to match. The Parks live in blissful ignorance, too content with the new “help” to notice that anything out of the ordinary. Only young Da-song, as a child would, begins to sniff out something rotten. Initially, the Kims’ antics are pure Machiavellian farce — and hilarious at that — as they nimbly choreograph their fraud, a scam that provides them the prosperity they desire — or at least a simulacrum that is close to reality.

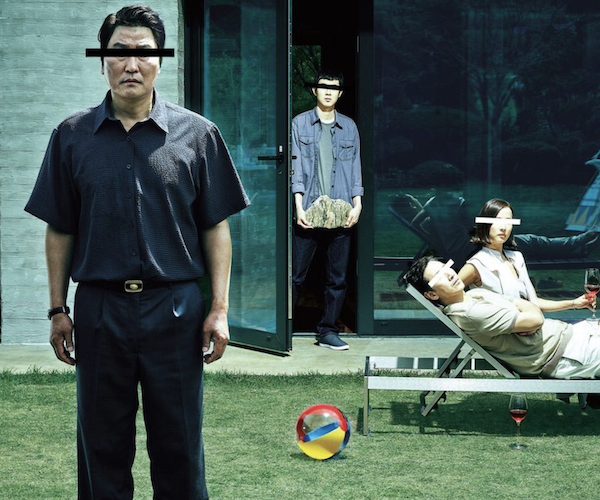

A scene from “Parasite.”

But the fun can only last so long, and Bong’s taut script cuts off the humor abruptly. The return of the Parks’ former housekeeper — who was unceremoniously set up by the Kims to be fired by Mrs. Park — reveals who the film’s titular parasites are. The Kims are not only sucking the Parks dry, but also setting up morally questionable schemes with other members of the underclass. The second half of Parasite is rife with unexpected plot twists and warped instances of violence that dramatize how tensions between the haves and the have-nots distort notions of good and evil.

Bong also nimbly uses visuals to infuse political commentary into Parasite. The color design of the two homes reflects the gaping chasm between the families: the Kims’ apartment is all darkness and greys, the Parks’ gorgeous home is a vision of light, with its floor-to-ceiling windows and stunning view of mountains and lush greenery. A masterful third-act sequence, in which the Kims must slink away from the Parks’ manse, alludes to Adam and Eve shamefully exiled from Eden. An image of downward motion is masterfully conveyed: the Kims trudge down endless stairways through a torrential downpour — only to find that their apartment is underwater. The sequence underlines that the Kims live a truly “underground” life. In this powerful picture of the existentially downtrodden there are equal nods to Marx and Dostoyevsky.

Recently, issues of social class have been getting their moment on the big screen. Last year’s Burning, directed by Bong’s countryman Lee Chang-dong, painted a sardonic vision of hard-pressed people yearning for a higher station in life, attracted to the gleaming status and accoutrements of a carefree upper class existence, but worried about what attaining it might cost them — morally and spiritually. Bong’s 2015 Snowpiercer, a dystopian tale of class warfare, can now be seen as an ultra-violent harbinger of Parasite. In the earlier film, the have-nots rise up to claim a modicum of dignity, if not prosperity. In Parasite, Bong’s approach is subtler and darker, a tragicomic exploration of the vicissitudes of existence on the margins — and how deeply people become dehumanized.

Neil Giordano teaches film and creative writing in Newton. His work as an editor, writer, and photographer has appeared in Harper’s, Newsday, Literal Mind, and other publications. Giordano previously was on the original editorial staff of DoubleTake magazine and taught at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.