Book Review: “Lampedusa” — Writing “The Leopard”

By Roberta Silman

Steven Price creates a mid-20th-century world that is filled with the same kind of conflicts that Lampedusa himself confronted in writing The Leopard, his great novel about 19th century Italy.

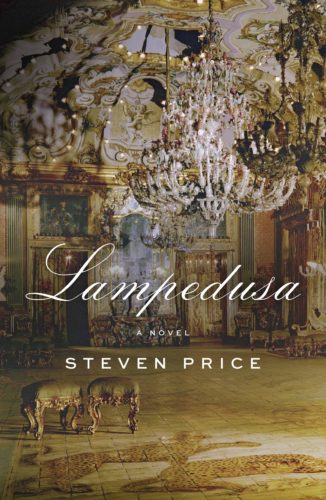

Lampedusa by Steven Price, Farrar, Sraus & Giroux, 336 pages, $27.

This review begins with a story that warms my heart, that will warm any writer’s heart. In 1958 Prince Giuseppe Tomasi de Lampedusa, a minor noble of Sicily, started writing a novel about the Risorgimento, which means “resurgence” in Italian but actually refers to the Unification of Italy in 1871. The Lampedusa Palace in Palermo had been bombed by the Allies during World War II and was now a ruin. Although married quite happily, Tomasi was also depressed at the thought of leaving nothing meaningful behind, so he decided it was time to write the book he had been thinking about for years: a novel based on his great-grandfather, Don Giulio Fabrizio Tomasi, another Prince of Lampedusa. When he was nearing the end of this project Tomasi approached, through intermediaries, the two most famous and prestigious Italian publishers — Mondadori and Einaudi — about getting his novel, Il Gattopardo, into print. Both houses rejected his work. Before putting the finishing touches on it, Lampedusa died of chronic lung disease at the far too young age of 61 in 1957, thinking his novel would never see the light of day.

Although he did not know Lampedusa personally, Giorgio Bassani, the Italian Jewish writer from Ferrara whom we know as the author of the immensely popular Garden of the Finzi-Continis and who was famous in Italy for many other novels and short stories and plays, read Lampedusa’s book and admired it enormously. Since he was also an editor at Feltrinelli (which, incidentally, had just published Dr. Zhivago to great acclaim) Bassani persuaded his colleagues to publish the novel and even edited it to completion. Although initial reviews were not good, Il Gattopardo was widely read and won the Strega Prize in 1959. It was translated into English as The Leopard and made into a movie in 1963 by the great Italian director Luchino Visconti, starring Burt Lancaster and Claudia Cardinale. As its readership grew, it was recognized as one of the great novels of the 20th century.

Reading this story, I was reminded of a professor of mine at Cornell whom I visited after I started writing short stories. “The work will find its way,” he told me. I’m not sure we can say that with confidence in this crazy age we now live in, but it was certainly true when The Leopard achieved its reputation. So, although he never knew it, Lampedusa had the last word.

And now we have a lovely, quiet, yet compelling novel based on Lampedusa himself and called Lampedusa. It is by Steven Price, the Canadian poet and novelist who is married to Esi Edugyan (whose novel Washington Black I reviewed recently); they met as students at the University of Victoria and have two children. What struck me while I read his book, besides imagining what their conversation might be like, was the great empathy I felt in both books.

There are many parallels and allusions to The Leopard in Lampedusa, but this new novel can be read on its own as an homage to the great Sicilian writer, to his country still recovering from the Second War World War, to the power of the knowledge of impending death, and to the yearning to leave what some people call “a mark in the world.” In the book, as in life, Giuseppe is married to Licy, an academic and a psychoanalyst who belongs to the Latvian aristocracy. Their marriage was clouded by Giuseppe’s extreme, almost pathological devotion to his mother, which results in arrangements that keep him and Licy apart for years and a childless marriage.

Author Steven Price. Photo: Penguin/Random House.

When Giuseppe discovers he has a terminal disease, he is propelled into writing the book he has thought about for years, the book that we know as The Leopard. So here we have a complicated man reluctant to reveal his situation, even to his wife and to his young friend Gioacchino, who has become like a son to him. A man who is determined to face himself and his flaws and the history of his family — especially his mother’s fraught past — with the kind of rare courage required of a writer when he is grappling with the anxiety that he may lose the fight against time. Here he is, about midway through the novel:

Some nights . . . he would lie awake and wonder at the hidden places inside him, the crevices and unswept corners of his self, and what lay within these. . . What surprised him was the nature of the fear inside him, how little it seemed to have changed. He supposed fear must be the one constant in his life. He could think back with great clarity to those fears of his childhood and see in them the seeds of the man he had become. It was fear that led to his shyness, fear that led to his voracious reading. And, too, it had been fear that led to the writing of the novel. He had been afraid as a young man in the artillery and afraid also in the prisoners’ camp at Szombathely. Fear had driven him to attempt to escape and fear, too, had drawn him to seek out the new friendships he had kept. He could find inside himself several of his earliest memories, loaded as they were with his fears, and he wondered now at all those others, those that were hidden from him and which he would not ever exhume. They too were a part of him. He did not want to die.

What is most remarkable in this novel, which has hardly any plot, is how Price develops his characters and their situation into a work filled with tension and surprises and hope, as well as fear. There is a lot here based on facts; but the internal thoughts of the characters are fiction, and some of the events may be fictional, as well. It doesn’t really matter because it all rings true. And the setting is so palpable we can feel the Sicilian dust and shabbiness, the smells, the heat, and the evening haze, as we watch this man complete the work he was meant to write, reinvigorate his love for his wife, face the pettiness of his relatives once and for all, and then, in a gesture of unexpected affirmation, welcome young people into his world so thoroughly that he and Licy end up adopting one of them.

Giuseppe also takes the reader into his confidence, so this book becomes, as many wonderful novels do, a work about the writing of the novel, about how a writer struggles daily to organize his thoughts to shape a work of art.

He still wished his life might resemble a novel. He was still young enough for that. He had wanted, he thought now, not only for a purpose, but most especially for a shape that might manifest itself; he had wanted for a sense of movement, of direction; he had outlived his beginning and desired whatever came next. He wished for what he had known in his childhood, but made richer, developed, brought to risk. No one is the narrator of their own life, he had observed once to Licy. A life is not a book, she had replied. Perhaps; but it seemed to him now that there were shapes, patterns, echoes in some lives that could nevertheless be drawn out, made sense of, and in this way a kind of insight might be attained. That was what he wanted. It could not be managed in the moment, only later, in just the way a narrative is shaped in a novel, by sifting through and selecting certain threads.

Thus, Price creates a mid-20th-century world that is filled with the same kind of conflicts that Giuseppe himself confronted in writing his novel about 19th-century Italy: between the old and the young, the aristocratic and the common people, the learned and those who still have much to learn.

Prince Giuseppe Tomasi de Lampedusa.

But at the end, in a witty twist, Price also presents us with his own gift: an afterword to the novel in the form of a final chapter called Relics (exactly as The Leopard ends), which takes place in 2003 from the point of view of Gioacchino, Giuseppe’s adopted son. In it, questions touching on autobiography and adaptation are addressed. There is also a letter from Giuseppe, which may or may not be real, and a brief summary of what happened after Giuseppe died.

In this final chapter Price reminds us that we each have our own desires, our own yearnings, our own stories. And that they are all of value, those of the famous and the ordinary, the rich and the poor, the gifted and the not so talented. Dependent on where we were born and where we live, because place may be far more important than we ever imagined. So may time. And our physical selves. And the dead whom we continue to love long after they are gone. Thus the end may be only a beginning. We are all part of the longer story as we are told in the last sentence of this impressive, beguiling book: “Our bodies are all doors [Gioacchino] thought to himself, and whether they are opening or closing is not for us to say.”

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Thank you Roberta.

I look forward to reading it.