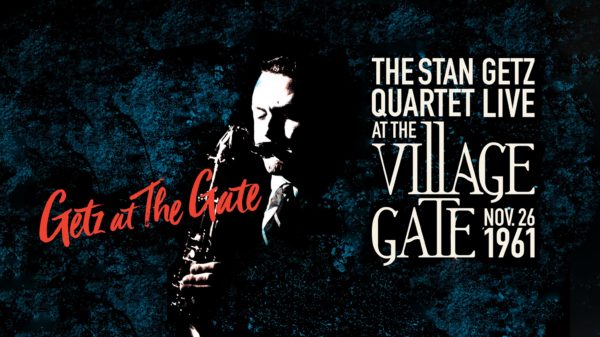

Jazz Review and Perspective: Stan Getz (and Everyone Else) in 1961 – “Getz at the Gate”

By Steve Elman

Saxophonist Stan Getz knew whom to listen to and whom to borrow from, and the repertoire for the 1961 Village Gate gig was particularly satisfying.

I have an abiding time travel fantasy. I want to be transported to New York City in December 1960 with about twenty grand in late-1950s currency in my pocket and a letter of introduction to Neshui Ertegun, who was then producing nearly all of Atlantic Records’ jazz sessions.

I’d get Ertegun to let me sit in the Atlantic control room on December 21 to hear Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Don Cherry, Freddie Hubbard, Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, Billy Higgins, and Eddie Blackwell record Free Jazz. I’d get Ertegun to introduce me to critic Nat Hentoff, and on January 10 of the new year, I’d worm my way into the Nola Penthouse Studio where Hentoff was producing Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp, Steve Lacy, Roswell Rudd, and Clark Terry in a session that would become known as New York City R & B. On February 9, I’d be at the Museum of Modern Art to hear Dizzy Gillespie’s quintet play the set that would eventually be released as An Electrifying Evening. On March 4, I’d be in Carnegie Hall, listening to Dizzy perform with a big band. In April, I’d use some of my precious cash to fly out to San Francisco to hear Miles Davis at the Blackhawk with Hank Mobley, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers, and Jimmy Cobb.

Back in New York in May, I’d wangle my way into producer Orrin Keepnews’s graces to sit in the booth at the recording session for George Russell’s Ezz-thetics. A bit more than a week later, I’d be in Carnegie Hall again to hear Miles with an ensemble led by Gil Evans, and the next night, I’d be at the Village Gate to hear Horace Silver’s quintet with Blue Mitchell and Junior Cook, listening to music that would eventually come out as Doin’ The Thing. Three days later, I’d use my hard-won behind-the-scenes credentials to be at Rudy Van Gelder’s studio to hear John Coltrane record Africa / Brass.

Stan Getz, BB (before bossa nova), Photo: Verve Records.

In June, I’d be at the Village Vanguard to see Bill Evans, Scott LaFaro, and Paul Motian in the groundbreaking trio performances that would become milestones in Evans’s career. In July, I’d be at Columbia’s 30th Street studio to hear the Duke Ellington Orchestra and Count Basie’s band make their only recording together. A little more than a week later, I’d be at the Five Spot to hear Eric Dolphy’s band with Booker Little. In early August, I’d get into the sessions that would become Max Roach’s Percussion Bitter Sweet, with Abbey Lincoln and Mal Waldron.

In the fall, I’d talk myself into visiting Lennie Tristano and listen as he recorded The New Tristano in his living room. In the first week of November, I’d be back at the Vanguard to hear John Coltrane’s quartet – yes, with McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison, and Elvin Jones, plus Eric Dolphy and Reggie Workman – in performances that would become just as legendary as Bill Evans’s during the summer. A week later, I’d be in RCA’s studios to hear Ran Blake and Jeanne Lee record together for the first time. A little after that, by now a good buddy of Neshui Ertegun, I’d be back at Atlantic to hear Charles Mingus record Oh Yeah.

Late in December, just about a year after my arrival in the past, I’d be back at Van Gelder’s studio to hear Grant Green and Sonny Clark record together, making some of the most important music in either man’s career. Then I could come back to the present, knowing I’d lived through one of the greatest years in music history.

Until a couple of months ago, I figured I’d have a free weekend after Thanksgiving in 1961. But then Verve released Getz at the Gate, and I knew where I would have had to be on November 26.

In November 1961, Verve’s producer Creed Taylor hadn’t yet introduced Stan Getz to Charlie Byrd or Joao Gilberto, and he probably was only marginally familiar with the words “bossa nova.” A month earlier, he had taken a major step forward in his career by recording saxophone improvisations over pre-recorded compositions for strings by Eddie Sauter – music that would eventually be released as Focus.

But when he took a post-Thanksgiving gig at the Village Gate that year, Focus hadn’t yet appeared in the record stores. Getz was considered a solid post-bop saxophonist, a more conventional rival to John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins (who was still in a self-imposed creative hermitage at the time). Even so, he was an astonishingly consistent performer, boldly advancing the ideas of Lester Young and Charlie Parker into the hard bop era.

So, when hip New Yorkers heard about this date, they would have expected Getz to program jazz standards and classic pop songs. He would have been expected to bring along some of Manhattan’s best musicians, and more than likely choose some young talent to spotlight. And the fans knew he would play superbly.

All of those expectations would be fulfilled. Getz knew whom to listen to and whom to borrow from, and the repertoire for the Village Gate gig was particularly satisfying. He programmed beautiful neglected standards – “When the Sun Comes Out,” “It’s You or No One,” “Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most,” and even an obscure Alec Wilder song, “Where Do You Go?”

He worked up Rollins’s “Airegin,” which in turn looks back to Lester Young’s “Tickle Toe.” He programmed Coltrane’s “Impressions,” at that time a very new tune – though it was based on “So What,” which Coltrane played with Miles Davis, and almost everyone in jazz knew its modes. He programmed Gigi Gryce’s “Wildwood” and Thelonious Monk’s “52nd Street Theme” – not planned as a throwaway for the Gate, but given a big stretchout, played loosely and uptempo, with everyone in the band getting a substantial say.

Pianist Steve Kuhn, still standing 58 years later. Photo: ECM Records.

As Bob Blumenthal so effectively describes in the CD’s notes, the bassist at the Gate might have been Scott LaFaro, whom Getz had employed regularly – but LaFaro had died just a month after his Village Vanguard date with Bill Evans. So Getz called on the bassist who had filled in for LaFaro in the Focus sessions, a Bostonian named John Neves.

Some of us were lucky enough to hear Neves after he returned to Boston and settled down, and we all knew he could have been much better known if he’d chosen the life of the itinerant jazzman. For us who knew him here, this release is a thrill – John Neves is alive again, beautifully recorded, in the prime of his career, supporting an artist of the first rank, contributing elegantly and forcefully.

On piano, Gatz had one of the guys everyone was talking about – Steve Kuhn, who had been part of Coltrane’s band earlier in the year. He draws on all of his resources when working with Getz – Bud Powell, Lennie Tristano, classical impressionism, and his own inner fire, standing stylistically almost exactly between Bill Evans and McCoy Tyner. In these 1961 recordings, he frequently employs a technique that in 2019 he uses more sparingly – long, fluid single-note lines in his right hand juxtaposed against percussive stabbing in his left, setting up a tension of approach that other pianists would find very hard to sustain.

And then there was the drummer – the ageless Roy Haynes. He was the old man of the group – at 35, he was one year older than Getz, four years older than Neves, twelve years older than Kuhn. He brought the authority of an original bebopper to the stand, along with the creativity of a restless intelligence that always sought new sounds and different percussion colors.

Haynes is still playing today, with even more ingenuity than he showed with Getz at the Gate.

Who would have thought that the oldest and the youngest guys in that band would be the only ones left standing 58 years later? Who would have thought it would take 58 years for this excellent music to be heard by people who never had the chance to get to the Gate that night?

Richard Seidel, a great and indefatigable jazz producer who continues the traditions established by Ertegun, Keepnews, and other dedicated predecessors in the booth, extricated this session from the Verve vaults. Thanks to him and his colleagues Zev Feldman and Ken Druker, we can all ride in the time machine again and sense what it was like to be there, back in the halcyon year of 1961, when nothing seemed like it could ever go wrong.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Tagged: Getz at the Gate, John Neves, Stan Getz, Steve Elman, Steve Kuhn

Hello Mr. Elman, you are very knowledgeable about those jazz greats of the ’50s. I was wondering if you have heard of or have any information about the drummer Art Mardigan who played with Getz, Woody Herman, and others?

Marcie – thanks for reading the piece, and for your question. I know Art’s work only from his recordings.

You may have seen his Wikipedia entry, which has more info than I had before reading it – for example, that his real last name was Mardigian. Link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_Mardigan

I also did not know that he was a Detroiter – born there and lived the last 20 years of his life there.