Book Review: “Rabbit’s Blues” — The Reserved Tenderness of Johnny Hodges

By Steve Provizer

Johnny Hodges was originally a Cambridge/Boston guy, and one of the most interesting sections of Con Chapman’s biography is his knowledgeable description of the local jazz scene in the 1910s and ’20s.

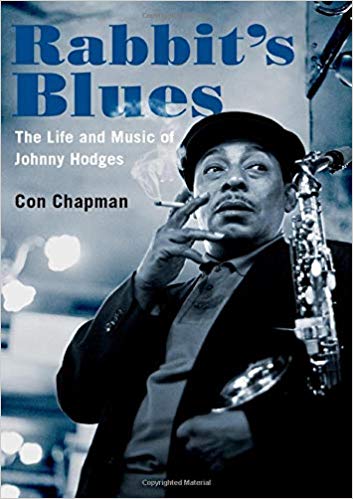

Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges by Con Chapman. Oxford University Press, 240 pages, $27.95.

Alto and soprano saxophonist Johnny Hodges was one of the most singular voices in jazz. He didn’t play the horn as much as sing through it. He made a large, long-term contribution to the music, both as a member of the Duke Ellington Orchestra as well as on his own. Hodges was also a somewhat inscrutable, taciturn, and quiet man, with a relatively uneventful personal life. This makes him a tough case for the would-be biographer, but author Con Chapman carries off the task well. Anyone who spends several pages just parsing out how Hodges got his nicknames (Little Caesar, Squatty Roo, Jeep, but mostly, Rabbit) has things under control.

This is not really a work that breaks a lot of new ground. There are no interviews conducted by Chapman listed in the footnotes, and it appears that the information has been pieced together from secondary sources. However, in putting together this biography, Chapman seems to have drawn on every source that offered even the smallest shred of information on Hodges. His authorial voice flows well; his interpretations of Hodges’s motivations, understanding of the man’s personality, and placement of his musical contribution in a wider context are viable.

Hodges, born in 1907, was originally a Cambridge/Boston guy. One of the most interesting sections of the book is Chapman’s knowledgeable description of the local jazz scene in the 1910s and ’20s. Hodges was a musical prodigy (and a natural truant). He picked up gigs as a pianist at rent parties at age 13, then started on the sax and began gigging on that horn soon after. In the early ’20s, he traveled back and forth in the “Boston-New York Pipeline,” finally moving to New York either in 1924, or 1925 — Chapman relates conflicting stories about this.

The biographer discusses what was a hot issue among musicians in the NYC jazz melting pot of the ’20s: the difference between “Eastern” style (New York City) and “Western” (everywhere else). This is an important discussion, one that potentially offers insights into the way jazz evolved. However, the musicians quoted here offer up contradictory descriptions of each style, and that ends up obfuscating more than it clarifies. I’m not suggesting that Chapman didn’t do his homework. This may just be a case of a problematic topic that is too complex and subjective to offer up neat conclusions

When he was a soprano sax–playing teenager, Hodges had the chance to see and even meet Sidney Bechet, who became an important early influence. Bechet later gave him a soprano sax that he kept throughout his life. Hodges took up the alto, and it was on that horn that he made his reputation. Interestingly, in 1940, after Hodges had been with Ellington for more than a decade, he stopped playing soprano in the orchestra. The reason? He wanted double pay for playing alto and soprano and Ellington wouldn’t give it to him. For many years, Hodges was the best-paid member of Ellington’s group, but their relationship, as depicted by Chapman, was complicated. One part of the difficulty was money. The other seems to have been sex and jealousy. Ellington was always surrounded by women and Hodges wasn’t. One could argue Ellington was successful with women because of his looks and status and/or because he bound his mistresses to himself by providing financial benefits. However one sees it, Hodges was (apparently) less successful. He was short of stature and less handsome than Ellington. Further, it galled Hodges that the deeply romantic quality of his playing provoked swoons — but not that much carnal activity.

It should also be noted that Hodges never became a great reader (sight reader of music) and he occasionally clashed with Ellington when he thought Ellington’s charts had strayed too far away from the blues, ballads, and the foundational style that made the orchestra famous.

Hodges’s sound gets full due in this biography, as it should. He was a great player at any tempo, but at slow tempos he shaped sound in a way that no one else ever has. Chapman makes a provocative conjecture that for many years the Ellington band was able to avoid having to hire a vocalist because the songlike playing of Hodges filled the emotional space that would have been taken up by a singer.

Hodges’s main competitor for primacy on alto sax was Benny Carter. It could be argued that their sounds were in the same “family,” although they were very different. In the late ’20s through the ’40s, most alto sax players (and some tenor sax players) modeled their playing after one of those guys — or possibly saxophonist Willie Smith. In all three cases, tone was the most valuable common denominator. A clear marker in jazz occurred when the influence of these players diminished — almost disappeared in fact — under the onslaught of Charlie Parker, who was less about a “pure” sound than about notes, harmony, and velocity. Parker’s influence grew during the course of the ’40s, until, by 1950, he had become “The Man.”

Saxophonist Johnny Hodges. Photo: Wiki Commons

John Coltrane spent half a year playing in a Hodges band in 1952, which gives Chapman the opportunity to devote pages to how Trane wrestled with his own sound. He notes how sweet tooth problems impacted Coltrane’s embouchure (Butter Rum Life Savers were the main culprit), and quotes Hodges saying that Trane was “having his teeth fixed all the time” and that Coltrane “came to fear the drill so much that it sometimes took two or more assistants to hold him in the [dentist’s] chair.”

Most jazz admirers will find this and a number of other incidents and anecdotes in the book fascinating. One such story concerns jukeboxes, which proliferated in the mid-’30s. Ellington had been recording for the Brunswick label, which charged 75 cents per disc. Competing labels charged only 35 cents retail and 19 cents wholesale. This priced Ellington’s music out of the market. Helen Oakley, a major if unknown force in jazz at this time, was hired by Ellington at the suggestion of his manager Irving Mills to put together sessions featuring subgroups from the Ellington band to record for the lower-priced Varsity Record label. These recordings made Ellington’s musicians a force in the jukebox trade and were also an aesthetic success.

A similarly intriguing incident deals with the effect of the imposition of the Cabaret Tax in 1944. This tax was levied on any NYC venue that served food, drink, and that allowed dancing. It was a 30-percent tax, which was then lowered to 20 percent — still significant. This tax was obviously an incentive for venues to hire music only for listening, not dancing, and this, in turn, paved the way for bebop music. One didn’t find any dancing joints on 52nd St.

On the debit side, there are times when I became frustrated by Chapman’s idiosyncratic approach to chronology, and that he does not attach dates to some events. (The volume contains an index and a list of sources that includes all the albums and CDs whose liner notes Chapman quotes from. There is not a complete discography.)

As I said at the top of the review, Hodges was a man of relatively few words, and many of those are contradictory. So, like a painter whose subject refuses to sit for long, Chapman is forced to limn Hodges’s personality in relatively few lines, and can only intimate what the hidden corners of the man’s emotional life might have been. However, Hodges’s music is what will chiefly concern most readers and, although lacking a few whys, Chapman does a thorough job with the whos, whats, and wheres.

Chapman bemoans aspects of the change to saxophone playing wrought by Charlie Parker, arguing that after him, “The kingdom of the alto was divided in two — like King Lear’s Britain.” On one side, you had the few who followed in the sonic wake of Hodges — Paul Desmond and Art Pepper, for example. On the other, you had almost everyone else. It led, Chapman asserts, to a diminution of the emotions that could be expressed in jazz. Of course, there are critics who demur, believing that Hodges’s playing sometimes veered toward schmaltz, and citing a record he made with the Lawrence Welk band in 1965. In fact, both Hodges and Ellington liked and admired Welk’s band (Louis Armstrong liked Guy Lombardo and Ray Charles enjoyed Jackie Gleason’s easy listening albums). My own opinion aligns with Chapman’s assessment of Hodges’s playing: “Hodges . . . kept his tenderness in reserve — never laying it on too thick — and used technique to express emotions without maudlin flourishes.”

Hodges’s record as an Ellington stalwart, bandleader, and recording maestro speaks — no, it sings — for itself, and this informative biography brings you closer to the song.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subject, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: Con Chapman, Duke Ellington, Johnny Hodges, Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges