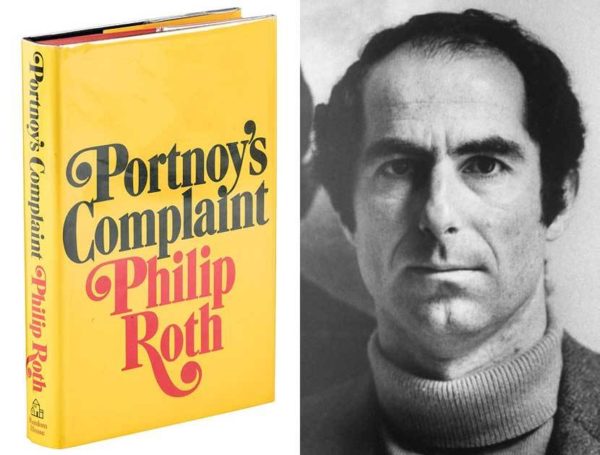

Book Commentary: “Portnoy’s Complaint” at 50

By Matt Hanson

Doctor, do you understand what I was up against? My wang was all I really had that I could call my own…

In the late ’60s, with a few books already under his belt, a young Philip Roth took his parents out to dinner in order to gently break some bad news. He had just written a new book that he figured might ruffle some feathers, and he wanted them to know in advance. Everything went fine, but in the taxi on the way back home his mother worried aloud to his father that her poor son had such delusions of grandeur — nobody was ever going to read his books!

Well, perhaps it was fitting that the joke ended up being on mama Roth. Portnoy’s Complaint, which turns fifty this year, not only became a runaway bestseller but indeed caused quite a cultural ruckus over its brazen, deliberately over-the-top language and controversial premise. Alexander Portnoy became a cultural anti-hero precisely because of his frustrated and highly articulate erotomania. The novel consists of a long and exasperatedly detailed monologue told by Portnoy to his mostly silent psychiatrist about the hormonal miseries that arise out of his dogged lust for shiksas, with their luscious Goyish blondness only driving him further into deepening spirals of manic self-abuse.

Portnoy lets loose verbally as much as physically, and part of the fun is trying to follow Portnoy’s creative but relentlessly self-lacerating accounts of trying and failing to find satisfaction. Cynthia Ozick argues that Roth was being aesthetically and politically brave by airing this kind of dirty laundry and treating it as a worthy subject for literature. It definitely gave him a racy reputation: Danielle Steele (not exactly a highbrow type herself) once opined that Roth was probably a great writer, “but I wouldn’t want to shake his hand.”

Here’s a characteristic scene that demonstrates the nature of what Portnoy’s complaining about and why. His mother has just expressed indignation over his lunchtime habits:

“’Hamburgers,’ she says bitterly, just as she might say Hitler; ‘where they can put anything in the world in that they want- and he eats them. Jack, make him promise, before he gives himself a terrible tsura, and it’s too late.’

‘I promise!’ I scream. ‘I promise!’ and race from the kitchen- to where? Where else.

I tear off my pants, furiously I grab that battered battering ram to freedom, my adolescent cock, even as my mother begins to call from the other side of the bathroom door. ‘Now this time don’t flush. Do you hear me, Alex? I have to see what’s in that bowl!’

Doctor, do you understand what I was up against? My wang was all I really had that I could call my own…”

Portnoy, like many adolescents, has more pent-up physical energy and hormonal urges than he knows what to do with. Jacking off is about far more than immediate gratification — it’s also a mini-rebellion against external pressures, from parents and the outside world at large. In a certain sense, Portnoy makes a connection that quite a few leftist radicals (Foucault and Wilhelm Reich come to mind) pointed out throughout the ’60s and ’70s — that orgasm equals liberation. Sexuality was how one distinguishes themselves from the rest of the herd. I’m not sure if Roth had this particular resonance on his mind when he wrote the novel, though it’s certainly possible. But seeing how little getting his rocks off helps Portnoy’s situation exposes the limits of that line of ‘sex is freedom’ argument.

A large part of what makes Portnoy work as a comedic character is that he is far too bright and excruciatingly self-aware not to realize what a schmuck he is. A character who isn’t aware of their own faults might well be tragic, but one who knows perfectly well how messed up they are, and keeps screwing up anyway, is an ideal setup for comedy. It takes a certain kind of person to find themselves aroused by a pound of liver, freshly bought from the butcher, that’s lying in their lap as they sit near an attractive girl as the city bus rattles and vibrates. Or who would think to take advantage of a hollowed out apple core while deep in the woods during a family picnic — and imagining it rapturously calling him “big boy” the entire time. Confronted with this kind of over-the-top humor a reader either laughs or recoils — there really isn’t room for a tepid response. Immortal lines like “I am the Raskonikov of jerking off!” and “let’s put the ID back in yid!” are designed to be uproarious to a certain kind of bookish (and presumably male) malcontent.

Perhaps the novel’s strongest parallels aren’t necessarily to be found in literature, however. With his impassioned self-loathing and almost performance-like monologuing, Roth’s anti-hero resembles an edgy stand-up comic. Roth was writing not long after the heyday of Lenny Bruce, another voluble Jewish lad who loved to take the piss out of himself and specialized in blue humor. There were plenty of comics (many of whom Jewish) who followed Bruce’s satirical lead in various ways, such as Woody Allen and Richard Lewis and, in a more civically minded mode, Jon Stewart. It’s not hard to imagine Alexander Portnoy himself up at an open mic. Some of the more slapstick elements of Portnoy’s obsession (his bodily fluids tend to get all over the place) also foreshadow the gross-out humor of Farrelly Brothers movies, especially the very popular There’s Something About Mary.

But anyone who’s heard a Trump speech knows where that kind of comedy leads to, the darker impulses that can lurk beneath male sophomoric laughter. There is an argument to be made — just check out some of the comments sections for this book on Amazon or Goodreads — that Portnoy is really no more than just a horny creep with a big mouth. He’s not exactly the kind of guy you’d want to bring around to meet your parents, that’s for sure. You’d at least want him to wash his hands first. While he affirms his staunch liberalism and high IQ score, those superficially mature aspects of his personality easily turn into the merely annoying and snobby — after all, nobody cares how well-read you are or how you voted if you’re running around humping the lunchmeat.

And then there’s the prickly question of Portnoy’s anguished relationship to his own Jewishness, engagingly explored and ultimately defended in Bernard Avishai’s book-length study Promiscuous. Plenty of critics, both Jewish and not, weren’t just offended at the risque outrageousness, they were either befuddled or horrified at how it portrayed the nuclear Jewish family as a slapstick Freudian nightmare of neurosis and guilt. The respected critic Irving Howe charged that the book was both a literary failure and social embarrassment; Roth was an ungrateful turncoat against the culture he’d initially made his name writing about. With, it should be added, Howe’s initial support. As a non-Jew, I have very little to add to these debates, but I can say that even though I had a very different cultural/historical background growing up than either Roth or his fictional creation did, as a younger man I found the book to be totally hilarious the first time I read it and even, ahem, pretty damn relatable. I was being raised in a very conservative religious environment myself. I’d never before read anything that spoke so directly, and with such raucous honesty, about this particular kind of angst.

In the olden days, our famed fictional anti-heroes tended to be adventurous rascals who roamed freely throughout the land and either escaped danger through sheer guile or shunned the hypocritical civilization that rejected them first. But in the (post)modern era, epic heroes of any kind start to look silly and ultimately hollow; nowadays our biggest emotional dramas are generally smaller, pettier types of inward struggles, c.f. J Alfred Prufrock’s “do I dare to eat a peach?” A writer highly attuned to the changes in style, tone, and subject matter in modern postwar fiction, Roth played up peevish Portnoy’s perpetually put-upon pursuit of pleasure to the adventurous hilt.

Rereading the novel again with the benefit of age and hindsight I still laughed plenty of times. but I’m not as won over by Portnoy’s candor as I used to be. Occasionally he seems like he could be one of the new Trump-worshipping incels (which stands for “involuntarily celibate”) despite being Jewish and a political lefty. His constant whining about his overbearing mother and his general misanthropy come off as insufferably adolescent even if nowadays he would be seen as well past middle age. But, at the same time, his self-obsession stoked by his incessant plights and gripes, he sounds strikingly contemporary. I can easily picture him with a constantly updated Twitter account and a well-thumbed Facebook page. Social media would be quite a delirious experience for Portnoy, as would the vast indulgences of the internet. Yes, the social mores he once railed against have loosened up considerably, and that might have cooled him down a bit. But, even then, I don’t think he would ever stop complaining.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

This Jew appreciates this thoughtful excellent piece by a non-Jew. You understand!