Visual Arts Review: “Renoir: the Body, the Senses” — Beauty and Dismay

By Charles Giuliano

When he is at his best, few can match Renoir’s charm and popular appeal.

Renoir: the Body, the Senses at the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, through September 22.

Renoir, “Seated Bather,’ 1914. Photo: Art Institute of Chicago.

In 2011 The Clark Art Institute deaccessioned Renoir’s Femme cueillant des Fleurs (Woman picking flowers). The rarely exhibited painting was estimated at $19 million.

That reduced to 32 the number of works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark. Their passion for Renoir would seem to know no bounds. Sterling’s diary entry, however, described a late nude, Seated Bather, as “a great big mushy gelatinous fat woman.” He was not alone in that response.

On every level the museum that the Clarks founded is among the most beloved and richly endowed of America’s mid-sized regional museums. It is particularly admired for its depth in Renoir.

Now, a century since the artist’s death, in collaboration with the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, the Clark is presenting Renoir: the Body, the Senses. The scholarly show of 75 works includes paintings, drawings, and sculptures — by Renoir and artists who influenced him as well as modernists who were influenced by him.

A tour of the moderately scaled exhibition generates a roller coaster of mixed emotions. There is unbridled joy in viewing familiar favorites; here and there pop up intriguing surprises. But there is also utter dismay. There is a gallery of late, grotesque, and bloated odalisques.

Large scaled sculptures, collaborations with Richard Gunio, represent a challenging encounter. Previously, we had seen only a few small Renoir bronzes. Further confusion in this exhibition comes with the inclusion of The Three Nymphs by Aristide Maillol. The large group in lead was too similar to ersatz sculptures by Renoir, which were more Gunio than Renoir. Today Gunio is remembered as an obscure Spanish artist who was a technician who worked with Renoir, Maillol, and other artists. Initially presented as sculptures by Renoir, Gunio later insisted on taking credit for them.

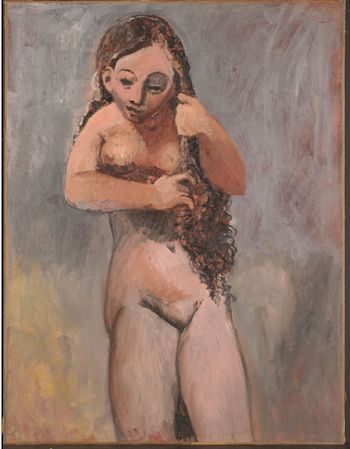

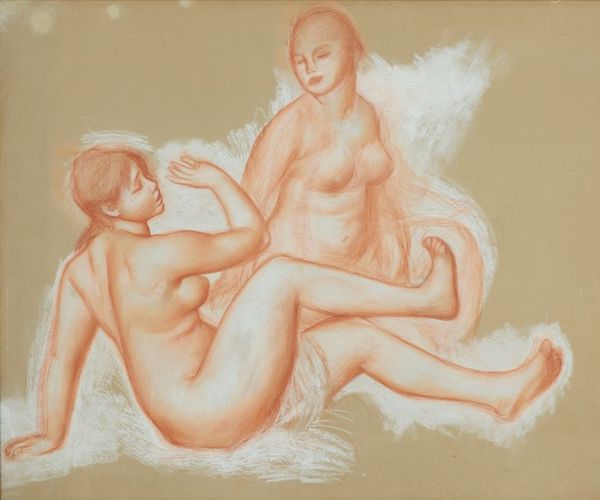

The most hideous work in the show is Two Reclining Nudes, 1968, by Pablo Picasso. If the point of the curators was to demonstrate the influence of Renoir, why include such a late painting? Picasso’s 1905 Nude Combing Her Hair features a frequent subject for Renoir — it provides a better comparison.

When he is at his best, few can match Renoir’s charm and popular appeal. His greatest works were included in the 1985-1986 blockbuster exhibition Renoir, which was shown in London and Paris before it came to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It broke MFA records with 500,000 plus visitors.

Missing in Boston was the greatest Renoir painting in America, Luncheon of the Boating Party (1886, Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.) ,which was seen only in Paris. However, the great dance pictures — Bal a Bougival, Dance in the City, and Dance in the Country — were magnificently reunited.

With those vivid memories we visited the Clark with an open mind. Enticing insights were to be found when examining Renoir’s formative years. He was employed by the Lévy-Frères porcelain factory in Paris. The technical development of decals made hand painting expensive and obsolete. Renoir and other employees took over, but the business failed. The business’s sense of decoration informed his early work.

Enrolling in the studio of Marc Gabriel Charles Gleyre (1806-1875), Renoir aspired to be included in the annual Salon. The scholarly catalogue discusses initial failures and works that he destroyed. He copied Old Masters in the Louvre. Referencing the latter experience is a delicious rococo painting Diana Leaving Her Bath by Francois Boucher.

Picasso, “Nude Combing Her Hair,” 1905. Photo: Clark Art Institute.

The Salons were full of nudes in the classical/ allegorical manner. They depicted women as fantasy. That changed with the realists Edouard Manet and Gustave Courbet. Renoir conflated allegory and realism with Diana the Huntress, 1867. The later Bather with a Griffon, 1870 is devoid of narrative elements. The picture’s colors are earthy and naturalistic with well defined forms.

The most curious and controversial painting, Boy with a Cat, 1868, is the first we encounter. Seen from the rear, with an emphasis on the body’s buttocks, its sex is not immediately clear. The head turned in profile is delicate; the boy is accompanied by a cat. As in Manet’s controversial Olympia, 1865, the cat is a signifier for ‘pussy.’ The label references a Hellenistic sculpture of a reclining hermaphrodite in the Louvre.

At the center of the show, in more ways than one, there are encounters with Renoir’s most accessible nudes. We are invited to compare and contrast works by impressionist peers Edgar Degas and Paul Cezanne. An intriguing juxtaposition: an austere, distorted Degas Woman Brushing Her Hair, 1884, contrasts with Renoir’s Blonde Braiding Her Hair, 1886. The Degas is a more ambitious work.

Renior’s masterpiece The Great Bathers, 1887 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), does not travel. It was his most ambitious work, created after he had viewed Titian and the Italian masters. He was striving for a new monumental classical impressionism. Some of the numerous studies for that painting, a relatively new acquisition from the Morgan Library, are displayed in a gallery with curved walls. These drawings are a revelation. They make us reassess Renoir as a draughtsman on a par with his peers Degas and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec.

Impressionist technique generated numerous problems to be solved. Traditional chiaroscuro yielded to the melting impact of filtered sunlight. The best example of Renoir’s solution is his Torso of a Woman in the Sunlight, 1875-76. I stood transfixed by this most paradigmatic of Renoir’s impressionist works. While fully depicted, the model is dissolved in filtered, blotchy light.

Renoir, Study for “The Great Bathers.” Photo: Clark Art Institute.

Compared to which, many of the mid-period nudes emphasize pretty, innocent faces and perky breasts. It’s that male-gaze factor that makes Renior an easy target for #MeToo. Martha Lucy examines the artist’s limitations well in her essay “Renoir’s Tactile Gaze.” With the exceptions of Degas and Lautrec, the impressionist artists had sex with their models. Some relationships went beyond that. Manet’s Victorine Meurant (Olympia) was formidable and demanded a partner’s share of the profits. Renoir’s favorite model was Suzanne Valadon, an artist and mother of Maurice Utrillo. There is a painting by her in this exhibition.

In Renoir’s late nudes pretty girls became puffy and matronly. There are no bones in sausage arms; models become blimps. That’s notable in a final painting, The Bathers, 1918-19. Understandably, Musée d’Orsay was flummoxed when it was donated by the artist’s sons in 1923.

This summer Charles Giuliano is publishing his sixth book, Counterculture in Boston: 1968 to 1980s.

Tagged: Charles Giuliano, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Renoir: the Body