Opera Album Review: Now Hear What Berlioz and Wagner Admired — Gaspare Spontini’s “Olimpie” in a Stupendous New Recording

This world-premiere recording of the 1826 Paris version of Gaspare Spontini’s Olimpie makes a powerful case for a composer much admired in his own day and for a work that forms a link between Voltaire and the French Grand Operas of Meyerbeer, Halévy, and Verdi.

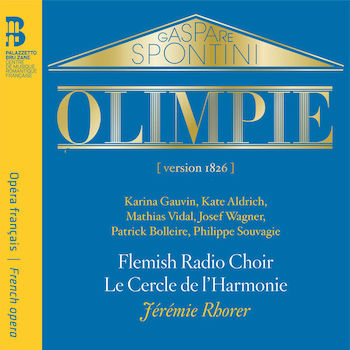

Gaspare Spontini: Olimpie (1826 version)

Karina Gauvin (Olimpie), Kate Aldrich (Statira), Mathias Vidal (Cassandre), Josef Wagner (Antigone), Patrick Bollaire (l’Hiérophante, also the shorter role of another priest in Act 2), Philippe Souvagie (Hermas) Le cercle de l’harmonie, Flemish Radio Choir, conducted by Jérémie Rhorer

Bru Zane BZ1035 [2 CDs] 135 minutes

To order online, click here.

The standard opera repertory often fails to include operas that were popular or influential in their own day. Fortunately, recordings—and, occasionally, enterprising theaters—remind us that certain works from the past, given half a chance, can still prove effective on stage. Recent productions have demonstrated the viability of works by such composers as Handel, Bellini (beyond Norma), Meyerbeer, Saint-Saëns (beyond Samson et Dalila), Dvořák, Zemlinsky, and Blitzstein. Several operas by Gaspare Spontini (1774-1851) should be added to this list. La vestale (1807) has been sporadically revived, notably in a vivid live recording (sung in Italian rather than the original French) that two remarkable singers, Maria Callas and Franco Corelli, made in the early years of their careers. La vestale can also be heard in more recent recordings, among which is one conducted by Riccardo Muti.

Now we have the same composer’s Olimpie, a work first performed in Paris in 1819 but heard here in an extensively revised version that Spontini made for performances in Berlin (in a German translation by E. T. A. Hoffmann, renowned author of the tales on which Offenbach would base his last opera). The Berlin version was then refitted in French—and further revised—for a Paris production in 1826. (The work is sometimes listed with the spelling Olympie; for performances in Italian, it becomes Olimpia.)

The 1821 and 1826 versions utterly reverse the events of the 1819 version, replacing a tragic ending—in which the three virtuous characters die and the evildoer, gnawed by regret, lives on—with a happy ending in which all but the evildoer survive. The 1819 version survives in a piano-vocal score. Perhaps some enterprising scholar-orchestrator will orchestrate the sections unique to the 1819 version (mainly in Act 3) and stitch them together with the sections of the 1826 revision that survive more or less intact. I’d buy that recording eagerly!

Olimpie participates in a particular strand of opera history: one that leads from Gluck to, each in his own fashion, Cherubini, Berlioz, and Wagner. This is evident in several ways. First, Spontini often connects one number to the next by averting a cadence and then creating a transitional link. Second, the work includes numerous passages of coloratura, especially in the leading soprano and tenor roles (Olimpie and Cassandre), but these are brief and do not emphasize vocal virtuosity for its own sake. The other three main roles (Statira, Antigone, and the Hiérophante, or High Priest) have even plainer—more consistently syllabic—vocal lines.

In both regards, the work (like others in the Gluck-Cherubini lineage) differs starkly from another major strand of operatic development, one leading from Cimarosa and Mozart through Simon Mayr and Rossini to Donizetti and early Verdi. Most operas in the Mozart-Rossini lineage focus frankly on vocal display and provide ample opportunities for applause at the end of a number (or at the end of a section within a number).

A third connection between Olimpie and the Gluck-Cherubini lineage is the rich workout that it requires of the chorus and orchestra.

(I simplify in all of this, of course, because certain works blend important elements from both lineages or traditions. Mozart’s Idomeneo, exceptional within his operatic output, frequently links the end of one number to the beginning of the next, thus removing an invitation to applaud.)

While listening to the new CD recording (which is also available on YouTube, Spotify, and other streaming services), I sometimes heard intimations of Wagner’s Lohengrin and Berlioz’s Les troyens. I particularly enjoyed several moments that set the vocal parts against highly rhythmic lines in, say, the low strings. I can well imagine Berlioz sitting bold upright (at a performance, or while reading the score) and thinking: “I could put that texture to splendid use in my own works!”

Composer Gaspare Spontini.

The big scenes involving chorus and soloists are not emptily grandiose but truly grand, recalling certain oratorio-like moments in Beethoven’s Fidelio, another opera that draws on aspects of the Gluck-Cherubini tradition. Opera historians also argue plausibly that Spontini’s emphasis on large choral scenes, religious ceremonies, marches, and dances paved the way towards French Grand Opera, as seen in such works as Meyerbeer’s Les huguenots, Halévy’s La juive, and Verdi’s Don Carlos. (Spontini’s dance movements are largely omitted in this otherwise near-complete recording of the 1826 Paris version.)

In order to wrap your mind around Olimpie, you will need to absorb the synopsis or, even better, scrupulously follow the libretto. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing in this case. The word “hiérophante” looks feminine, but the role is for a bass. The two main male characters have names that likewise might seem female: but the French name Cassandre here means Cassander, and Antigone means Antigonus. Also, four of the five male roles are for baritone or bass, making them hard to distinguish by ear. (One upside of the profusion of low-male roles: the sole tenor—the courageous and unjustly accused Cassandre—stands out.)

The plot derives—quite distantly, in the happy-ending version recorded here—from a play by Voltaire. (An essay by Olivier Bara in the book that comes with the CD recording explains in authoritative detail the many ways in which the Voltaire tragedy, the original 1819 opera, and the revised 1821 and 1826 versions of the opera differ.) Fifteen years before the action of the opera begins, Antigone arranged for the great conqueror Alexandre (Alexander the Great) to be poisoned and for Alexandre’s wife Statira to be stabbed (though the wound does not prove fatal). Cassandre was seen removing the dagger from Statira’s chest and giving Alexandre wine that (Cassandre did not know) had been poisoned by Antigone. Cassandre took the baby Olimpie to safety from her blood-soaked cradle.

The events of the opera (which I condense greatly here) take place in and around the temple of Diana at Ephesus, an important Greek town on the coast of what is today Turkey. Cassandre and the beautiful slave Aménaïs (i.e., Olimpie, now 15 years old) are in love and intending to marry.

In Act 2 Cassandre reveals to Statira and Olimpie what actually happened on that day long ago, thereby making clear to both of them that Aménaïs is in fact Olimpie, daughter of Statira and Alexandre. Statira still worries that Cassandre was “my assassin.” In Act 3, the guilt-ridden Antigone (mortally wounded by Cassandre) admits his guilt and kills himself, Statira mounts the throne, and Cassandre and Olimpie marry amid radiant expressions of relief and gratitude from the people of Ephesus. Antigone, eager to deflect his own guilt, spreads rumors among the soldiers that Cassandre was responsible for the attacks on Alexandre and Statira. The priestess Arzane then interrupts the wedding, railing against Cassandre and, in the process, revealing that she is in fact Statira, widow of the great Alexandre.

All five major roles—in descending order by vocal type: fifteen-year-old daughter, widow-mother, accused murderer, actual murderer, high priest—are well limned in libretto and music. And, despite my earlier remarks about the score’s emphasis on seriousness, dignity, tableau-like massiveness, and scene-to-scene continuity, there are many moments in which the reliable pleasure of solo and duet singing carry the day. The powerful role of Statira was “created” (as one says in the opera world), in both the 1819 and 1826 versions, by the mezzo-soprano Caroline Branchu, greatly admired as a singing tragédienne by the young Berlioz and others of that generation. Vocal fanciers will adore the concise proto-Bellinian duet in Act 2 for Olimpie and Statira, which revels in florid singing in thirds and sixths and touching appoggiaturas. In Act 3 Olimpie gets a rather Mozartean scene and aria—with aptly expressive short passages of coloratura—that would make a fine item on an aria-recital CD.

The cast members here pronounce the sometimes archaically worded text with clarity and precision. The most secure vocalist is soprano Karina Gauvin (from Québec province), as Olimpie. Gauvin—though 50 years old at the time of the recording—displays meltingly beautiful high notes, handles trills and mordents with liquid ease, performs crescendos and diminuendos on single notes with great aplomb, and appropriately threads notes together by means of portamento. I have previously admired her artistry in roles as different as the fiery Vitellia in Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito and the deeply suffering Mother in Debussy’s L’enfant prodigue.

Mezzo-soprano Kate Aldrich (born in the state of Maine) sings with much dramatic point and variety. Her tone, which, when soft, is as exquisitely controlled as Gauvin’s, becomes tremulous on long notes at mezzo-forte and louder. Still, the richness of her lower register helped me distinguish her voice from Gauvin’s.

Tenor Mathias Vidal has a firm core to his sound, with a plangent quality that draws the listener in. I have previously admired his skill and insight in operas by Catel, Saint-Saëns, and Ravel.

The three low-voiced males, including bass-baritone Josef Wagner (from Austria) are more than adequate but sound rather similar. All have a slight shudder in their tone (a slow, though fortunately not wide, vibrato). The low notes of the high priest (Hiérophante) are insufficiently resonant, undercutting his authority.

The recording was made in mid-2016 over the course of three days. Two days later, the same performers gave the work a much-praised concert performance at the Théatre des Champs-Elysées. (With a different Statira they repeated it five months later in Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw.) The energy and insight that these performers bring to the work is apparent in the excerpts on a two-minute trailer.

The Flemish Radio Choir sings splendidly, and the period-instrument orchestra, under its founding artistic director Jérémie Rhorer, makes consistently interesting, colorful, and apt sounds, helpfully assisted by the resonant acoustics of the Philharmonie de Paris. The large-ensemble scenes (e.g., end of Act 2) have a lift and forward impulse that help explain what Berlioz and Wagner—and, yes, Meyerbeer, Halévy, and Verdi—learned from Spontini’s operatic craftsmanship.

Particularly toothsome are some dramatic entries by the brass, played in the raspy manner favored by such early-music conductors as Nikolaus Harnoncourt. An instance can be heard at the beginning of the scene in Act 1 in which Antigone welcomes his warriors and the people of Ephesus into the temple of Diana for the wedding of Cassandre to—as Antigone will learn to his dismay—the slave Aménaïs (i.e., Olimpie).

The carefully calibrated writing for winds and for muted and unmuted strings (explained in the accompanying essays) is much more audible here than in two earlier recordings of the opera, both currently unavailable except as used copies or via streaming: a 1950 live performance in Italian with the young Renata Tebaldi; and a 1984 radio-broadcast from Berlin that is in French (not always well pronounced). Both of those recordings used a version of the score that was published after Spontini’s death and that blended aspects of 1821 Berlin and 1826 Paris.

All in all, the new recording unveils a fascinating work by an inventive and influential composer whom many of us know only as someone whose works were admired by Berlioz and Wagner. (Wagner conducted La vestale in German translation in 1844.) Olimpie is a major discovery, made possible by the team of musicologists at the Centre de musique romantique française, an organization whose headquarters are at the Palazzetto Bru Zane (in Venice). The recording comes with a smallish hardcover book containing the libretto and highly informative essays, all in French, with English translations. Unfortunately, the translations are not up to the level of quality otherwise maintained by the scholars of the Centre/Palazzetto, being frequently too literal (e.g., “caducity,” which should be “old age” or “later years”; “prosperous God,” which should be “God who brings prosperity”; and “deplorable mother,” which should be something like “mother much to be pitied”).

That single gripe aside, this Olimpie is one of the most revelatory opera recordings that I have reviewed in the past few years.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).