Book Review: “In Extremis” — A Flawed Heroine

By Roberta Silman

In Extremis is required reading not only for anyone interested in war, but for anyone interested in how an unusual woman makes her way in the world.

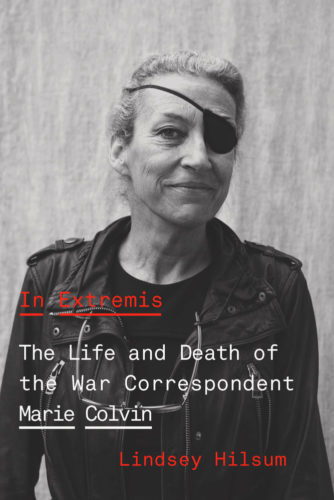

In Extremis: The Life and Death of the War Correspondent Marie Colvin by Lindsey Hilsum. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 400 pages, $14.95.

We all have heroes who inspire us and nourish our own work, whatever that might be. Not surprisingly, my heroes are often dead women who wrote fiction, like Charlotte Bronte and George Eliot and Willa Cather. Or poets, like Anna Akhmatova and Elizabeth Bishop. But before I wrote fiction I was a journalist, a science writer for The Saturday Review, from 1958 to 1960. Although the Science Section was a monthly affair, I was familiar with the pressure of putting out a weekly magazine, and for about ten minutes — during an interview at The New York Times because they were looking for a woman science writer — I considered making my life in journalism, but confessed that what I really wanted was to have a family and try my hand at writing fiction.

It was the right choice for me and I have never regretted it. But I have always been fascinated by those very special women who choose to go into war zones to get a story. Thus, two of my contemporary heroes since the turn of the century have been the American correspondent Marie Colvin and the English correspondent Lindsey Hilsum. And now their fates have become intertwined forever because it is Hilsum who has written this riveting biography of Marie Colvin, who died so tragically in Syria in 2012.

Only someone familiar with the turbulent life these women lead could have written this biography, and Hilsum has done a superb job. Like all great achievers, Marie was a complicated person, and Hilsum confessed in a recent interview that she got to know Marie better in death than she ever did in life. As she lays out in the Preface:

I had known her so fleetingly—a dinner in Tripoli, a bumpy drive through the West Bank, a drink in Jerusalem—and now she was gone. There was so much I didn’t know about Marie, things she had hidden from me, or that I had chosen not to see. What drove her to such extremes in both her professional and personal life? Was it bravery or recklessness? She was the most admired war correspondent of our generation, one whose personal life was scarred by conflict, too, and although I counted her as a friend, I understood so little about her.

As grief subsided, I thought of her no less often. She was always there, her ghost challenging me to discover all I had missed when she was alive.

So, we are warned. This is a life filled with pain — literal and figurative — a life lived on the edge in all kinds of ways and that affected not only those close to Marie, but many on the periphery. A life that leaves the reader in awe, and also in anger. But a life that, as soon as one starts to read, you feel you have to get to know as well as possible.

Marie Colvin was the eldest child of five in a Catholic family that was, as her mother Rosemarie said, “lace curtain Irish.” Within a few years of her birth in Astoria, Queens, the family moved to a house in Oyster Bay and although her father Bill spent his whole career as an English teacher at Forest Hills High School, the family’s life was centered in that small suburban town and its closeness to the sea. She loved to swim and became a good sailor and although she did well in school, she was usually bored. Always the first to court danger as a child, Marie became quite a handful by the time she reached high school; she was a liberal and an activist, restless in the extreme and a lot more interested in sex than her conservative father would have wished. By her junior year the solution seemed to be to send her on an AFS program and she spent most of 1973 as an exchange student in Brazil where she seemed to grow up exponentially. She came home a young woman — “calm and defiant” — and much more aware than her peers or her family that there was a big world out there and she was going to carve a place for herself in it.

She had also caught the travel bug, and the summer before she entered Yale as an undergraduate she ended up in Mexico where she ventured into dangerous, risky situations, never deterred by the simple fact that she was a woman. At Yale the pattern continued, but she was smart enough to know she had to pay attention in some quarters. She was very influenced by John Hersey who taught there and whose important book Hiroshima changed her own way of looking not only at war but at the human condition. Ordinary people who found themselves in the most extreme situations, like those in Hiroshima which used as its model, Thornton’s Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey, one of my mother’s favorite books. It soon became clear to Marie that journalism was a place where she could thrive and her hero became Martha Gellhorn, who had covered the Spanish Civil War and the D-Day landings and who had the same kind of moxie (and insecurities) that Marie would develop over time.

But there was another side of Marie, the social animal, and at Yale she was drawn to the wealthy party givers and goers, the girls who wore fashionable clothes, the boys who led carefree, often drunken lives. She learned she could hold her own, that she could light up a room and attract both men (as boyfriends and lovers) and women (as friends). But in 1977, when she was a junior her father Bill died of cancer. He was 50 and Marie was 21. It was an excruciating blow. She never had the chance to show him what she could do, and, even more important, to sort out the unresolved issues between them. One wonders what her life might have become if she had had the steadying influence of the father who seemed to understand her better than anyone else in the world but who had left her in a kind of limbo she would never escape.

Hilsum is very good at balancing Marie’s work life and personal life as we follow Marie’s achievements: working on a newsletter for the Teamsters Union, then a stint at UPI where she got interviews with Muammar Gaddafi that were the failing press service’s last gasp and started her on the road to fame as a woman who could do what no one else could. In September 1986 she landed a job at The Sunday Times of London, moved to that city on a Monday, went to her new job in an “Agnes B dress, big newsroom, felt out of place, but proud.” The very next morning she was off to Beirut.

“The Sunday Times” was a really good fit, partly because English journalism was a lot freer than American journalism at that time. Correspondents could use the word “I” and get to heart of the matter, which included their own feelings as they observed the atrocities that surrounded them. Marie’s style was exactly what they wanted and after her coverage of the first Iraq war and her friendships with Saddam Hussein and Yasir Arafat which yielded an amazing series of interviews, John Witherow, who had become the editor wrote: “our intention is to promote you as the paper’s star writer and scoop merchant. All you have to do is deliver!”

Until I read this book I had no idea how wide-ranging Marie’s reporting was — how she seemed to be wherever there was real conflict and the need for a witness to chronicle the worst kind of human suffering. Such a life, even one punctuated by three marriages (two to the same man) and lots of lovers and sailing vacations and what looked like a lot of high-living in London takes its toll. Her friends and former lovers were often worried; she suffered from bouts of depression and bulimia and an underlying problem of anorexia. She worried about her appearance; she drank too much and had times when she seemed unsure and bewildered, yet when she was needed in the field, she seemed above all fear. Some of the most moving parts of this book are when Hilsum takes us back to Oyster Bay, to her mother and her siblings who clearly did not understand many of her choices, who were always there for her but who worried about her constantly. Especially about the drinking which became more and more of a problem as she went into her 40s and 50s.

I also had no idea about the ins and outs of what it means to be a correspondent, some of the pressures on individuals to forge the friendships one needs and how to avoid the people who are determined to stand in your way. Getting into war zones is no easy matter, and Marie was a master at it. She also made enemies along the way; indeed, there is evidence that her death was targeted by Assad, who wanted to silence her. Hilsum is wonderful at these complicated maneuverings, and her book flows at a compelling pace that never, as Grace Paley used to warn, “stinks of research.” Moreover, as we read, we feel a mounting fear as we get to know not only Marie but her friends and colleagues. Who will make it out of this encounter? Who will not?

Marie Colvin at 35. Wiki Commons.

Marie Colvin was hit by shrapnel and badly wounded while embedded with the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka in April of 1999. It was a harrowing experience that ended in a New York Hospital where it was determined that she would have to lose an eye. From then on she became the icon with the eyepatch, but at that point her life took a turn that would lead into a downward trajectory that seemed inexorable. For there was no way she could stop doing what she was doing. As she said in a piece in The Sunday Times in April 2001:

Why do I cover wars? I have been asked this often in the past week. It is a difficult question to answer. I did not set out to be a war correspondent. It has always seemed to me that what I write about is humanity in extremis, pushed to the unendurable, and that it is important to tell people what really happens in wars—declared and undeclared.

Her personal life was also lived in extremis, as she continued to take risks in all her relationships. She became both more fearless and more needy: “Marie was easy to love and hard to help.. . . but Marie reacted to advice on drinking as she did to advice on relationships—she listened, brow furrowed, head to one side, and then ignored it.”

And war reporting was becoming more and more dangerous. After her friend, the photographer Joao Silva was badly injured when he stepped on a mine, Marie gave an address in London on November 10, 2010:

The expectation of that blast is the stuff of nightmares. We also have to ask ourselves whether the level of risk is worth the story. What is bravery , and what is bravado? . . . . But . . .someone has to go there and see what is happening. You can’t get that information without going to places where people are being shot at, and others are shooting at you. The real difficulty is having enough faith in humanity to believe that enough people, be they government, military, or the man on the street, will care when your file reaches the printed page, the website, or the TV screen. We do have that faith because we believe we do make a difference.

She made a difference, like her friends Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondos, who were also killed earlier in the Middle East. And like so many whose names we don’t know.

After Gaddafi was killed Marie went to Babu Amr, a neighborhood in Homs where Syrian rebels were determined to do the same to Assad. She did some of her best pieces about the struggles there, and everyone thought she was finished. But she and Paul Wood went back even though almost everyone else had left. Paul had “a bad feeling.” Assad’s people traced the Media Center from which she had filed her reports and a rocket injured Paul and killed her instantly on February 22, 2012. The pages describing Marie’s last days are as riveting as anything you will ever read. And the sudden realization that this amazing presence, this astonishing woman is gone forever, is overwhelming.

In Extremis is required reading not only for anyone interested in war, but for anyone interested in how an unusual woman makes her way in the world, how a ten-year old who insisted on taking the greatest risks when she and her siblings played Dead Man’s Branch could become the heroine she became — with all her flaws and mistakes — because of her profound “faith in humanity.’ In this present-day world where it is easy to become cynical and disaffected by our horrendously awful leadership, this biography is an inspiration and should be read and talked about, especially to the young. It is about ideals and aspirations and the faith not only in humanity but in a better world.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.