Book Review: “Five Cities” — Urban Meditations on Turkish History and Culture

By Vince Czyz

Five Cities is a species of psychogeography, a deep map, that weighs the effects of topography, urban environments, and monuments of the past on mood and perspective.

Five Cities by Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar. Translated by Ruth Christie. Anthem Press, 228 pages, $15.95.

Turkish authors writing toward the middle of the 20th century have long been neglected outside of Turkey, and while their names are still overshadowed by Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk, Pamuk’s success has generated enough interest in his compatriots to inspire English-language editions of their books.

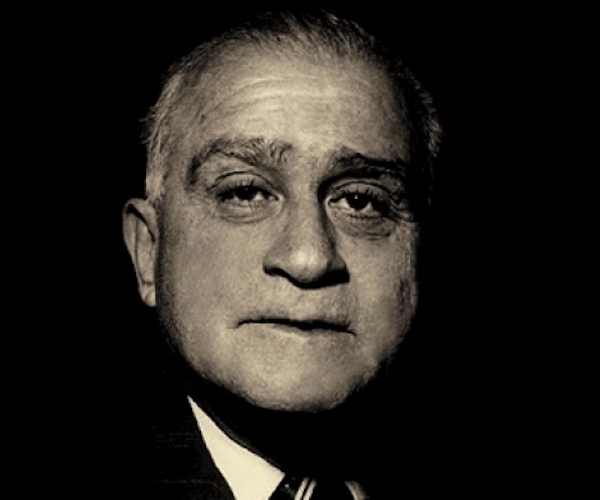

Among them is Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar, whom Pamuk himself considers the greatest Turkish novelist of the previous century. Tanpinar, who was born in Istanbul in 1901 and died in 1962, was also a poet, critic, and an essayist. Of his essays, none is more famous than the series he wrote on Ankara, Erzurum, Konya, Bursa, and Istanbul — offered as the collection Five Cities. Originally published in 1946, although many of Tanpinar’s recollections are of experiences that precede that year by decades, it was revised in 1960.

He begins with Ankara, the nation’s capital as of the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923. He imagines the city, located north and west of Turkey’s center, as “a legendary warrior” and the broker of the fate of Anatolia (Asia Minor). Here, Tanpinar points out, the Ottoman sultan Beyazit II was defeated by Tamerlane, and here was the seat of the new government set up by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk after the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. Here also, Tanpinar observes, is a meeting place for “Turkish culture and older civilizations”: Turkish saints lie “side by loving side with Roman and Byzantine tombstones … here a capital or an architrave in Ionian style springs from a brick wall; over there, on the steps for a Moslem tomb, appears an ancient stone that celebrates a Roman consul’s arrival in the city …”

As becomes clear by the second essay, this is not simply a book about cities but about a number of converging motifs, including the land itself. Tanpinar begins his essay on Erzurum with childhood memories of an 11-day journey he and his family made by camel. His great-grandmother acts as his guide, telling him the names of stars and mountains as well as recounting folktales and legends. “Poetry,” Tanpinar comments, “religion, the yearning for one’s country, the experiences of life, the remnants of belief like successive lives that flit through our dreams, elevated mountains and streams to the rank of sacred and saintly beings.” The city itself, doing a brisk trade with Persia, is prosperous and its marketplaces thronged. He visits Erzurum again as a young man but is horror struck by the devastation wrought by World War I and the War of Independence, fought between 1919 and 1923. “What was actually lost,” he laments, “was a complete way of life, a whole world.” Noting that Erzurum was once “a truly oriental medieval city,” he records the loss and tragedies its people suffered.

Tanpinar makes a third journey to Erzurum, this time by train, just after World War II. He is encouraged by how much of the city has been rebuilt, but he ends where he began, with the land itself. The distant mountains, he reflects, “perhaps revealed the secret of the bitter melancholy in our people’s soul, the source of Anatolia’s poetry and its sense of yearning.” Here he touches on a theme that Pamuk would later make central to his own book-length essay, Istanbul: Memories and the City.

Tanpinar describes Konya, the third city, as “a true child of the steppe with which it shares a mysterious beauty.” Famous in the west for being the adopted home of the Persian poet Rumi, whom the Turks call Mevlana, Konya was also home to the Whirling Dervish sect, founded by Mevlana. Tanpinar spends a good deal of the essay discoursing on Mevlana, Sufism, and Mevlana’s collaboration with Shams of Tabriz, whom he credits with inspiring Mevlana to live “beyond the worlds of forms and appearances.” Tanpinar ends with a passage on Konya’s prison and his recognition of the timeless genius of Turkish folk songs to convey Central Anatolia’s “burden of exile, fate … and the loads of pain and bitterness.”

Tanpinar sees Bursa, far to the west and just south of Istanbul, as the “purest touchstone of the Turkish soul”: “Whatever changes, disasters, periods of neglect or sages of good fortune it underwent, it has always retained the atmosphere of that early period when it was founded.” The city’s eternal aspect moved Tanpinar to a meditation on time in which he imagines a “second Time” at work. “Alongside the time in which we live laugh and enjoy ourselves, work and make love is another Time, very different, much deeper, unrelated to the clock and the calendar, a creative and indivisible Time which, like an eternal season in this city’s atmosphere, is regulated by art and history and life lived with passion and faith.” The renowned last stop on the Silk Road, Bursa is the point of departure for the book’s most metaphysical musings.

Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar, poet, novelist and critic, was a professor of Ottoman and Turkish literature at Istanbul University.

The longest, most detailed, and most in-depth essay by far is the final essay on Istanbul. A collage of ethnicities, Istanbul is a city of nostalgia and of the melancholy that abides throughout Tanpinar’s Turkey: “The oil lamp, the street half-lit by gaslight, the voices of beggars, the watchman’s cudgel, the fear of fire, the mournful whistle of ferryboats, and the strange psychological states caused by too intense a religious life nourished sadness in an almost mathematical way.” This sadness is mitigated by the city’s architectural beauty and geographical splendor. Split by the Straits of the Bosphorus, Istanbul spreads over seven wooded hills and is bounded by two seas as well as an inlet whose name, the Golden Horn, reflects the effulgence it takes on at sunset. A “Bosphorus morning,” writes Tanpinar, “is an entirely different delight from any other neighborhood’s.” Istanbul is also a city of “exaggerated shadows,” “little corners and unexpected views,” venerable trees (he dwells on these as rivals to Istanbul’s magnificent Ottoman architecture), coffeehouses and the disappearing neighborhoods of tradesmen. Tanpinar finds the loss of the latter particularly painful, but throughout this essay — and in various passages throughout the book — he laments the losses modernity has brought. Wrestling with the problem of “how and where” we should “relate to the past,” Tanpinar ends his account of Istanbul, and the book, with a tentative solution.

Ultimately, Five Cities is a look at Turkish history and culture as refracted through these urban centers and the Turkish psyche, primarily Tanpinar’s own. It is a species of psychogeography, a deep map, that weighs the effects of topography, urban environments, and monuments of the past on mood and perspective. It includes personal reminiscences, quotes from Ottoman historians, snippets of poetry composed in different centuries, personal anecdotes, the stories of Turks Tanpinar encounters, and glimpses of Turkish folklore and legend.

One caveat: the changes Tanpinar has observed and opined over have multiplied and grown by magnitudes since he wrote this book. Istanbul, for example, was a city of some 800,000 in his time; it’s now home to nearly 16 million people. The trees he so loved have mostly been uprooted — the 2013 Gezi Park uprising was sparked by the proposed destruction of yet one more green space — and vast neighborhoods of shoddy apartment blocks have sprung up all over the city.

Nonetheless, Five Cities, ably translated by Ruth Christie, is a first-rate achievement and an important addition to any collection in which Turkey features prominently. Indeed, the book goes beyond regional interest, posing questions germane to all of us about memory, loss, preservation, change, and about that aggregation of architecture and human beings, that locus of so many social and commercial transactions, known as the city.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.