Book Review: “El Norte” — Recovering a Greater America at the Southern Border

By Jeremy Ray Jewell

Rather than focusing on Mexicans in the United States, historian Carrie Gibson posits an expansive transnational history.

El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America by Carrie Gibson. Grove Atlantic, 576 pages, $30.

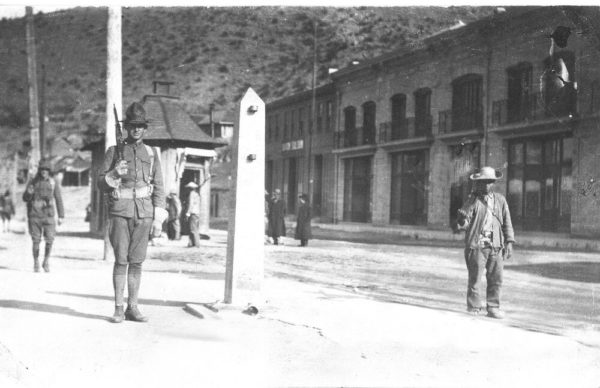

The border between Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora during the Mexican Revolution.

I shared some drinks recently in the Mexican border town of Reynosa, Tamaulipas. My interlocutor was a local, with a long history in that frontier town. For my part, my roots in my hometown of Jacksonville, Florida go back to at least the second Spanish period. That’s when my ancestor Burroughs Higginbotham, who held land to the north of the St. Mary’s River in Georgia, received a land grant from the Spanish to the south of that river in East Florida. It was there where he married his wife Isabella, who consensus designates as having been either Spanish, Florida Minorcan, indigenous, or… something other.

Some of my earliest memories include the Castillo de San Marcos, the conquistador’s morion helmet and the Cross of Burgundy. When young, I learned that St. Augustine’s Matanzas Bay was named to commemorate the Spanish massacre of the Huguenots in present-day Jacksonville at the hands of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés. And I heard at least one elder proclaim that Nathan B. Forrest High School would change its name as soon as Pedro Menendez High School did (the former changed its name in 2014, the latter has not). I read Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ classic novel about a childhood in Florida, The Yearling, and heard my own experience echoed in it:

“Is there any Spaniards hereabouts now?”

“There’s nary a man livin’, Jody, has even heered his grandpappy say he’d ever seed a Spaniard. The Spaniards come from acrost the ocean, and went tradin’ and fightin’ and marchin’ acrost Floridy, and no man knows where they’re gone.”

The business of the spring woods went forward leisurely in the golden morning. Red-birds were mating, and the crested males were everywhere, singing until Baxter’s Island dripped with the sweetness of the sound.

“Hit’s better’n fiddlin’ and guitarin’, ain’t it?” Penny said. Jody came back to the scrub with a start. He had been halfway across the ocean with the Spaniards.

– The Yearling

What my recent Mexican interlocutor and I discussed were borders. We both knew borders. Very specific borders, at that. They were the borders between two Americas. My border was Florida, and theirs was the Rio Grande Valley, or el Valle de Tejas. But our border experiences were similar. In some ways, we had both grown up in the same place — and also “halfway across the ocean” — at the peripheries of our own worlds, and in the peripheries of each other’s.

Carrie Gibson’s El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America, was the history book I needed growing up. It tells the Spanish and Hispanic history of the modern United States, often known in Latin America as simply “El Norte” (not to be confused with the region of Mexico of which the US Southwest was once a part). The volume begins with the earliest Spanish forays and continues into the interventions and large-scale migrations that took place ever since, back and forth, across the ambiguous borders between “us” and “them.” El Norte seeks to recast the history of the United States as seen from its peripheries. It is a past that is often told in terms of an Anglophonic east-to-west progression rather than of a Hispanophonic south-to-north. Of course, the latter has never been lost on those of us who grew up in those areas and have longed to see a counter narrative to the dominant Northeastern national origins mythos.

After setting up the requisite foundations of Spanish history in the hemisphere (Colombus to Cortez), Gibson moves onto the explorations of Hernando de Soto through the southeast and then to the establishment of Spanish Puerto Rico, Florida, Texas, New Mexico, and California. Challenging and complicating the all too black-and-white notions we have of these actions, she takes us through the processes of US expansion and annexation of these lands, and the subsequent histories of their peoples inside and outside our borders. We learn of the troubled legacy of Juan de Oñate, conquistador and contemporary Southwestern symbol of Hispanic heritage — or indigenous genocide, depending on who you ask. We learn of Spanish Louisiana governor Bernardo de Gálvez’s campaign against the British in West Florida during the American Revolution. And we learn about the efforts of the young republic’s would-be trans-Appalachian states of Franklin and Kentucky to team up Spain against their coastal opponents. Along the way we are introduced to individual actors from the United States, such as James Wilkinson, officer in the Continental Army and Spanish spy, and William Walker, the piratical ‘filibuster’ from Tennessee who attempted to usurp governments in Mexico and Nicaragua in the name of an ambitious “Golden Circle” of slave states from Virginia to South America. We are also introduced to some crucial problems raised by these traditionally overlooked histories.

After setting up the requisite foundations of Spanish history in the hemisphere (Colombus to Cortez), Gibson moves onto the explorations of Hernando de Soto through the southeast and then to the establishment of Spanish Puerto Rico, Florida, Texas, New Mexico, and California. Challenging and complicating the all too black-and-white notions we have of these actions, she takes us through the processes of US expansion and annexation of these lands, and the subsequent histories of their peoples inside and outside our borders. We learn of the troubled legacy of Juan de Oñate, conquistador and contemporary Southwestern symbol of Hispanic heritage — or indigenous genocide, depending on who you ask. We learn of Spanish Louisiana governor Bernardo de Gálvez’s campaign against the British in West Florida during the American Revolution. And we learn about the efforts of the young republic’s would-be trans-Appalachian states of Franklin and Kentucky to team up Spain against their coastal opponents. Along the way we are introduced to individual actors from the United States, such as James Wilkinson, officer in the Continental Army and Spanish spy, and William Walker, the piratical ‘filibuster’ from Tennessee who attempted to usurp governments in Mexico and Nicaragua in the name of an ambitious “Golden Circle” of slave states from Virginia to South America. We are also introduced to some crucial problems raised by these traditionally overlooked histories.

The Texas Revolution loses some of its glamor once we learn how that political union of Tejanos and Anglophone “Texians” was cynically entered into by those interested in expanding the South’s institution of slavery. A collaboration that later was to lead to marginalization and violence. Mexicans in Texas, including Tejanos who had supported the Revolution, would be granted an ambiguous status in Texas society for over a century, vulnerable to Jim Crow segregation as well as lynchings. Following the discovery of the Plan de San Diego during the Mexican Revolution, in which some Mexicans conspired to overthrow the white supremacist governments of the South and Southwest, a campaign of terror carried out by the Texas Rangers ensued (“rangers” being a peculiarly Anglo institution originally). Other events, such as the long controversy over New Mexican land grants, the Mexican Repatriation (1929-1936), and the Zoot Suit Riots (1943) take on a new light when seen through Gibson’s prism of US-Mexico history on the Anglo-Hispano border.

The volume’s perspective is delicate to maintain in our tribalized world, but valuable. Rather than focusing on Mexicans in the United States, Gibson examines an expansive transnational history: Cubans and Puerto Ricans are part of the story, but not as identity interest groups who yearn to be part of a gradually “more perfect Union.” That simple liberal ideal may propel the targeted marketing goals of Univision or Telemundo — but it is counterproductive when it comes to understanding our shared post-colonial realities. Yes, all of the groups confronted Jim Crow as well as Anglophonic ideas of race. But, in Gibson’s history, the peoples of the Americas are seen far more multidimensionally; they are inheritors of colonial and racial ideologies of their own as well as representative of sibling national and political ideologies.

What I take away from Gibson’s work is not, as another reviewer has described it, a debunking of “the myth of American [United States] exceptionalism.” Quite the contrary, it could be equally claimed that the book debunks Latin American concepts of exceptionalism. I claim neither. My take away is that this is a historical synthesis which, expanded upon and applied across different time periods, suggests a new Pan-Americanism, a hemispheric paradigm of the global pueblo. This is what historian Herbert E. Bolton proposed in his 1932 presidential address to the American Historical Association, “The Epic of Greater America,” where he argued for a more holistic approach to American history. This vision is the ideal outcome of what Argentine semiotician Walter Mignolo has more recently called “border thinking” or “barbarian theorizing.” If we can learn to know, deeply, the kind of literal and mental borderlands explored in Gibson’s El Norte, then we can hear “the other side of the frontier begin to talk, and talk the language of civilizations, but from the experience and knowledge and memories that civilization despises.” It is unsurprising that Bolton dedicated so much of his work to borderlands. We learn about ourselves when we learn about what is going on at our edges. This interaction echoes the Turner Thesis, that the American West has defined our national culture. Interestingly, Mexico has a very similar conception of the role its borderlands have played in its national development. Our peripheries help define our centers.

For too long children like me have thought, as Rawlings’ characters did, that the “Spaniards” had simply gone. Many, of course, left for Cuba, from whence some of their descendants most likely returned to Florida. But Spanish Florida didn’t disappear; it became part of the state’s history. And that adds another interesting dimension to Gibson’s chronicle. As the author notes, “United States values, culture and institutions were not just formed in New England, or in a vacuum.” This argument resonances with the Southern aspect of my Florida background. The American South is often said to constitute a internal ‘borderland’ within the United States. Thus the zany cultural mix-and-match: my Florida Christmases were equal parts fir trees substituted for poinsettias and Santa Clauses in flip flops. Reimagined Spanish tradition on one hand; postmodern gaucherie on the other. Silly, perhaps, as Gibson describes St. Augustine’s kitschy tourist trap — the Fountain of Youth. But that inanity didn’t come out of nothing. It was formed on a border. And borders are inevitably silly places.

Jeremy Ray Jewell is from Jacksonville, Florida. He has an MA in History of Ideas from Birkbeck College, University of London, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Massachusetts Boston. He maintains a blog of his writings entitled That’s Not Southern Gothic.

Tagged: Carrie Gibson, El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America