Book Review: The Critic as Wildean Artist — Peter Schjeldahl’s Elements of Surprise

By Robert Israel

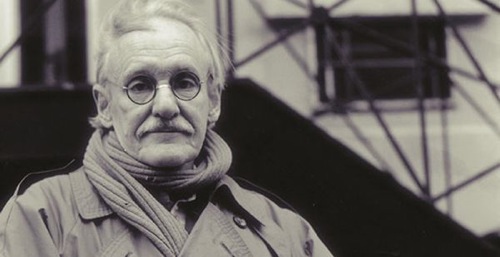

Peter Schjeldahl debunks (and praises) works of art, while also acknowledging the strategic importance of beauty.

Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light: 100 Art Writings 1988-2018 by Peter Schjeldahl. Abrams, New York, $28.

One of the keys to Peter Schjeldahl’s approach to art criticism can be found in the final essay of his new collection. Titled “Credo: The Critic as Artist – Updating Oscar Wilde,” Schjeldahl, The New Yorker’s 77-year-old art critic, states that he has freely adapted Wilde’s “razor-edged assaults on dreary, timid, deadly attitudes toward art” as his own métier. “I pledge allegiance to Oscar Wilde’s model of art criticism,” Schjeldahl declares, adding: “While praising beauty, [Wilde] demonstrates its utility as a weapon.”

I am not recommending readers turn to the end of Schjeldahl’s book simply because this essay is such an incisive summary of the critic’s beliefs. It is because this “credo” is the perfect preface to the 99 pieces of “razor-edged assaults” to come, an explanation of how (and why) he wields his critical “weapon.” And he uses that weapon very well. He debunks (and praises) works of art, while also acknowledging the strategic importance of beauty.

And there’s another valuable reason to look carefully at this “credo.” Schjeldahl is an anomaly among contemporary art critics in that he lacks an academic pedigree. His formal education ended with his high school diploma. Readers who approach art criticism expecting acknowledgement of contemporary theory will be disappointed; Schjeldahl cites art scholars, but his preference is to tell the reader, via Midwestern plain speech, what he sees and what he thinks we should find in art.

It doesn’t hurt for an art critic to have exercised his artistic imagination, so it makes sense that Schjeldahl started his career as a poet. He later abandoned that path and, for awhile, gave up writing criticism as well once he began doing drugs. “In a contest between meeting deadlines and doing drugs, guess what won,” he confessed recently in a New Yorker piece (not included in this collection). To his credit — and our benefit — he kicked the habit and met his deadlines.

Many of the pieces in Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light appeared in newspapers that have since vanished. Schjeldahl — again, in the aforementioned New Yorker piece — credits his work for The Village Voice and 7 Days, first as a stringer and later as a staff writer, with educating him in the discipline of the craft. He has high praise for copy editors, despite how they made life more difficult. Back in the day, dealing with newspapers that used linotype machines, he learned how to suture his pieces together after a number of (salaried) editors tore his copy apart.

Schjeldahl, in the thirty-year span this book covers, demonstrates that he has evolved into a passionate craftsman and illuminating critic. His words, to quote British novelist Ford Maddox Ford, are like “pebbles fetched fresh from a brook.” Several of the pieces in the book — some mere paragraphs in length — come from the pre-computer age; he unearthed them from newspaper morgues. He admits that all the articles in this collection have been revised, but there is nothing wrong with hindsight. Their judgements on the artworks he critiqued (in museum collections, published books, and catalogs) continue to stimulate. What more can we ask of arts criticism? The exhibitions may have closed, but his sharp assessments stand as acts of discrimination, one way (among others) to understand the artists he wrote about.

Visual arts critic Peter Schjeldahl — For him, beauty is a weapon. Photo: Poetry Foundation.

An example of Schjeldahl’s writing that is illustrative of his grasp of artists and their legacies can be found in his 7 Days piece on the late Jean-Michel Basquiat, who died of a heroin overdose at age 27 in 1988.

Basquiat may be a martyr to nothing except the Russian roulette of a dope habit. But there’s no denying that his reputation, which will ultimately rest (securely, I believe) on the quality and significance of his art, underwent weird inflations and deflations. The art world enabled his rise. For a while, he helped define it. Then much of it turned on him.

Schjeldahl knows the perils of drug abuse first-hand but, more important, he sympathetically probes the condition of the artist, their social and psychological challenges. He believes that Basquiat self-consciously transformed himself, shedding a life filled with the “passions and humor of insurgent youth in a chaotic metropolis” for a “deepening of his identity as a black artist.” Wielding his Wildean weapon, he descries that Basquiat’s “distillations” have “adorned walls of rich, white, perhaps in every sense patronizing collections from Dusseldorf to Tokyo.” He is further repulsed by the art world’s shallow treatment of artists such as Basquiat. “But the true question bears on what he did do,” the critic concludes, “which the art world took up and then let drop, both carelessly.”

Finally, back to the volume’s conclusion. Schjeldahl claims that one of the most important tasks a critic can do is to insert an element of surprise to their judgments. “Readers should not be able to predict, with precision, what we will say on a given subject,” he argues, “because we can’t know, ourselves, until in the midst of saying it.” All criticism is autobiographical — an articulation (confession?) of what art teaches us about ourselves.

And, to this critic’s credit, he is difficult to pin down. Along with this elusiveness, Schjeldahl expresses his delight in the art he sees before him with an adroit wit. And he conveys a convincing warmth for the artists under review. But his empathy does not obstruct the resoluteness of his verdicts, which are articulated with honestly, precision, and audacity.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel, and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Tagged: Hot Cold Heavy Light: 100 Art Writings 1988-2018, Peter Schjeldahl