Book Review: “Little Dancer Aged Fourteen” — A Kind of Apotheosis

By Peter Walsh

In more pedantic hands, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen could easily have been a tedious and frustrating read. Instead, despite the dense and ultimately inconclusive source material, the book is continuously fascinating.

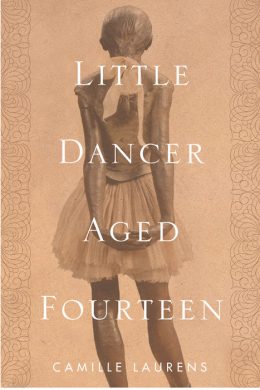

Little Dancer Aged Fourteen: The True Story Behind Degas’s Masterpiece by Camille Laurens, translated from the French by Willard Wood. Other Press, 176 pages, 26.95.

Edgar Degas’s ballet dancers are some of the best known works of art in the world. Originally created in multiple different media and reproduced uncountable times, these images of dancers in rehearsal, at rest, or on stage have been especially popular with generations of parents of young girls. For them, the ballet tutu and toe shoes represent the purity and innocence of preadolescent femininity.

Historians of the period have long known better. In the decadent late nineteenth century, the Paris Opera recruited its apprentice dancers mostly from the city’s poorest and most desperate classes. The lives of the youngest trainees, the “little rats” as they were called, were hardly romantic. The Opera required them to live within walking distance because their meager salaries didn’t cover the cost of car fare. Poor mothers pushed their daughters into the ballet to bring a few more francs into a household that often couldn’t pay the rent, even in the city’s most downtrodden districts, and in the hopes there might be other benefits.

Defenseless against the abuses of the ballet masters and subject to a grueling work schedule with harsh fines for absenteeism, the little rats suffered far worse from the Opera’s patrons. A season ticket admitted wealthy men backstage where they could mingle freely with these children. These are the formally dressed gentlemen in top hats that lurk at the edges of many of Degas ballet compositions. Far from living innocent lives, the little dancers were frequently the victims of institutionalized child sex trafficking.

Degas himself was not one of the top-hatted lurkers. But he was drawn to the Opera Ballet for a long stretch of his career, from about 1860, when he was a young painter, to 1890. He was not alone. Although the ballets themselves served mostly to fill interludes in the singing that allowed the audience to mingle, visit the boxes, and gossip and intrigue (examples of these meetings appear in the Lon Chaney version of Phantom of the Opera), the dancers’ sometimes tawdry lives, complicated romantic liaisons, and perhaps, in particular, their scandalously short costumes, outraged and fascinated the Parisian public and foreign visitors. Besides Degas, the ballet milieu inspired many other artists, novelists, and popular journalists.

But for the real young women, their futures were grim. According to Camille Laurens’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen: The True Story Behind Degas’s Masterpiece, published in French in 2017 and now released in an admirable English translation by Willard Wood, they barely knew how to read. After years of toil, a lucky handful of little rats would work their way up through the corps de ballet to solo roles, perhaps even stardom, followed by a longer career as ballet instructors. Others might find a wealthy patron to support them. For most, there were no guarantees and few options: perhaps a few better paid gigs as an artist’s model, prostitution, destitution, crime, an unhappy marriage, early death.

One of these little rats, Marie van Goethem, middle daughter of poor Belgian immigrants living in Paris, escaped, posthumously at least, her designated fate. Degas chose Marie to model for, among other projects, one of his most celebrated works: a bronze figure of a skinny adolescent, somewhat less than life size, head upturned, her inelegant features set in an inscrutable expression of defiance, her legs in fourth position, and dressed in a real ballet costume and with a real ribbon tied around her long, bronze hair. The piece is known as “Little Dancer Aged Fourteen.”

Portrait of Edgar Degas. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Despite the classicism of Degas’s style (Ingres was an important influence), he was in fact the most disturbingly modern of all the Impressionists— this in the context of the major public scandals created by Manet’s “Déjeuner sur l’herbe” and “Olympia,” among many others. “Little Dancer” is no exception.

Degas himself never saw the “Little Dancer” in bronze. The composition gave him a lot of trouble and required at least twenty-six preparatory studies, naked and clothed, as well as three-dimensional maquettes in a reduced scale. Degas shaped the final wax laboriously, with many revisions, over an armature that, present day X-rays reveal, incorporated whatever he had to hand in the studio—paintbrush handles, drinking glasses, rags, wood shavings, cotton wadding, cork stoppers.

Usually a wax model forms a step in casting the finished sculpture in bronze. But, though he struggled to complete the work, it isn’t clear that Degas ever intended to cast the “Little Dancer.” Apparently, many of the wax figures he made were only “documents,” not intended for exhibition or sale but only “for [his] own satisfaction.”

Degas exhibited “Little Dancer” just once, in a glass case at the Salon des Independents of 1881, where it created another scandal: Viewers were particularly offended by the nude, rendered in corpse-hued wax dressed in real clothing, like a store mannequin or a doll, and by the way Degas mixed the sublime and the gutter in unsettling ways. “[R]efined and barbarous,” wrote the prominent critic and novelist Huysmans, “an admixture of grace and working class vileness.” Of course, Degas’s model embodied the same contrasts in real life.

“Little Dancer” was discovered still intact in Degas’s studio after he died in 1917—although her costume had shredded during decades of neglect—along with dozens of other wax models of dancers and other figures that had also never been cast.

Degas was not known as a sculptor and lived as an ailing recluse during the last years of his life. So the extent of his three-dimensional work surprised almost everyone. After a brief discussion, the artist’s family had the piece transferred to a foundry, where it was first translated into a plaster mold and then cast in bronze for an edition of 22, each fitted out with real ballet costumes and hair ribbons, just like the original. By the mid-20th century, these casts were bought and sold for many millions. An avid American collector acquired the original wax in 1956 and it has been in the United States ever since.

The “Little Dancer” can be seen in Paris, London, New York, Washington, Dresden, Copenhagen, in Cambridge, MA, at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, and at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Reduced-size replicas can be purchased for a few dollars from many places, including from amazon.com.

For Parisian novelist and essayist Laurens, the “Little Dancer” and, more particularly, Marie van Goethem, have become a bit of an idée fixe. Her short book is obsessively researched. In her quest to unwrap the many mysteries in the work, its artist, and its young model, Laurens has plumbed dozens of volumes — accounts by Degas’s friends, biographies, historical tomes, even the novels the work has inspired. She has spent many hours scouring the employee records of the Paris Opera and searching the online archives of the French state. She leaves the distinct impression she has unearthed every scrap of information about the Little Dancer that there is to dig.

Edgar Degas’s “The Little Dancer.” Photo: John Stillwell/PA Wire.

Still, the verifiable details, especially ones about Marie herself, are few and far between. Aside from her birth record, the details of her Paris Opera work, police records of various family escapes, and the images Degas made of her, almost nothing of Marie has survived — not a single letter, note, photograph, or possession. We have no idea what she meant, if anything, to Degas as a human being. “You don’t even know the date of her death,” Laurens reproaches herself late in her narrative.

In more pedantic hands, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen could easily have been a tedious and frustrating read. Instead, despite the dense and ultimately inconclusive source material, the book is continuously fascinating. What starts off as a fairly straightforward art historical essay gradually morphs into social commentary, biography, psychological study of the roots and costs of creativity, even a personal memoir of Laurens’s own family and childhood. Though her book’s roots are thick in the ground, Laurens’s prose is clean and clear.

Laurens’s search takes her to some strange places: Degas’s love life (or lack of one), his working methods, the fate of immigrant children in the 19th and 21st centuries, the casual sexism of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists — “women’s hands are lovely to paint,” Renoir wrote, “as long as they perform housework” — the rigors of climbing the ladder at the Opera Ballet, and the abrupt, and apparently unwanted, end of the author’s own ballet training. Laurens even works in her great-grandmother’s perfume shop and salon, the slow rise of her family from working class to bourgeoisie, and her grandmother’s reputation for elegance and fine manners.

She also traces the careers of Marie’s two sisters, who had also been little rats: the older one, Antoinette, from petty crime to relative comfort thanks to a patron followed by an early death, the other, Louise-Josephine, into her emergence as a star of the Opera Ballet and a later career as a ballet teacher. She would die as the respected mistress of the minor painter Fernand Quignon (1854–1941). But of Marie herself Laurens writes, “the little dancer just flew away.”

At times, the book spends more time on its digressions than its subject. Inevitably, Laurens fills gaps in the narrative with educated guesses while decrying the fantasies other writers have made of Marie’s life. Yet somehow she pulls all this miscellany and speculation into a single coherent and satisfying narrative of less than 150 pages. If only for her conciseness, she deserves our admiration. For Marie van Goethem, it is the kind of apotheosis she probably never dreamed was possible.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than eighty projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.

Tagged: Camille Laurens, Little Dancer Aged Fourteen, Other Press, peter-Walsh