Book Review: Anthony Powell — Among the Most Modern of 20th Century English Writers

Although Anthony Powell’s stock has gone down since he died in 2000, I hope that this new biography will spark interest in A Dance to the Music of Time.

By Roberta Silman

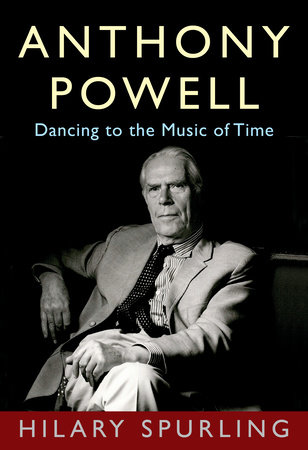

Anthony Powell, Dancing to the Music of Time by Hilary Spurling. Knopf, 453 pages, $35.

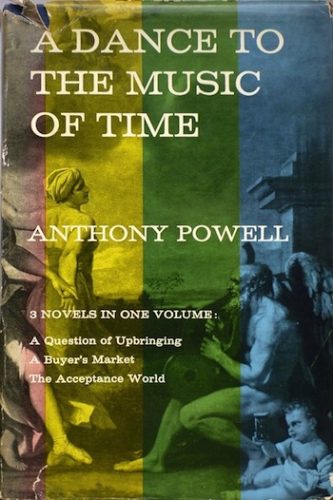

How we come to read certain books is a mysterious process. Not long after my husband died on August 1st I gravitated toward a favorite book, Must You Go?, Antonia Fraser’s memoir of her life with Harold Pinter. As I read, I discovered that Fraser was the niece of Anthony Powell’s wife, Violet Pakenham Powell, which was an amazing coincidence since I had been thinking it was time to re-read A Dance to the Music of Time, Anthony Powell’s great opus of the 20th century. Twelve books written at top speed between 1951 and 1975 which became required reading in the ’60s and ’70s, along with all of Evelyn Waugh and The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell. I still love a lot of Waugh, I must confess that I don’t know anyone who re-reads Durrell, but I suspect that a whole new generation will start reading Powell. For in many ways he is the most modern of the 20th century English writers, and there are long stretches of Dance, which gets its title from a Poussin painting that Powell first saw in the Wallace Collection (it still hangs there) that are superb.

But before committing to such an ambitious project, it might be a good idea to read this new biography of him by Hilary Spurling. I know only her two volume biography of Henri Matisse, which is one of the best biographies I have ever read. She is clearly a woman of great talent and taste and has written about other heroes of mine: Paul Scott, Ivy Compton-Burnett, Pearl Buck, and Sonia Orwell (anyone connected to Orwell is surely worth reading about).

You will not be disappointed. Spurling knew Powell who pronounced his named “Pole” although we in America are inclined to say it more phonetically: Powell. And she has given us a very sympathetic picture of a man who wasn’t always sure of his path, made some mistakes especially as he got older (publishing his Diaries seems to be a universally acknowledged gaffe), but who was a person of real substance, who was loyal to his wife and children, who stuck to his principles, who helped and defended his friends (especially Waugh after that brilliant contemporary died in 1966 at 63), and who had the same kind of intangible warmth and mystery as many of his characters.

An only child of a strange marriage — his mother was more than a decade older than his father — his beginnings were lonely and none too secure, since the family’s finances were always uncertain. Sent away to a miserable boarding school at ten, he entered Eton when he was 13 and Balliol College at Oxford when he was 18. Never good at sports, he was a good draughtsman and loved classical music and read enormously and noticed everything. After Oxford he went into the publishing business in London, which reads as almost more chaotic then as it is now.

For someone like me, who is interested in all that literary gossip, this biography is a gold mine, but even if you don’t know all the characters and their back stories, it is still fascinating to read about these writers who made their livings in the publishing business — who bought what books and why, who betrayed their friends by rejecting their manuscripts or writing bad reviews of their books, who slept with their friends’ mistresses, usually the vampy girls who seemed to gravitate towards writers and artists then, and perhaps always. Also interesting is Powell’s gift for friendship with an eclectic group: Constant Lambert, Gerald Reitlinger, Malcolm Muggeridge, Henry Yorke (who became the writer Henry Green), Nina Hamnett, the Sitwells, Evelyn Waugh and his first wife who was Evelyn Gardner, George Orwell and his wife Eileen, to name just a few. Some of the friendships held, others did not. But he took the risks that friendships require even though he was innately shy.

While earning a pittance of a living in publishing Powell actually wrote several novels before the Second World War, married Violet Pakenham in 1934 and had two sons. But he was floundering and he knew it. After the War there were periods of despair — he was prone to depression, and he always seemed to be plagued, as his father was, with financial pressures. In 1948 he published a biography of John Aubrey, who was a biographer himself, and one of the things that had stuck with Powell after reading so much about Aubrey was that “the paramount need for a writer was stability, seclusion and a workplace free from the noise, the expense, the intrusions, and the increasing social demands of London life.” London in the 20th century was no different from London in the 17th century when Aubrey wrote. Probably worse. So at the end of 1952, just after the first volume of Dance was published to good reviews, he and his family moved to Chantry, a shabby house in the west of England which they loved and whose grounds he worked on until he died.

In his later life Powell would say his ambition was to have a wife with a title and a house with a circular drive. (I suspect that was more tongue-in-cheek than has been acknowledged.) He had married well, but it was only when he was in his 50s and his always parsimonious, sometimes cruel father died that Powell came into real money. It turns out that his father had been a secret saver and left Tony and Violet and the boys what would be almost two million dollars in today’s currency in 1957. One of the great surprises of the younger Powell’s life, which couldn’t have come at a better time.

One of the reasons we read great novels is to learn better how to live. And one of the reasons why Powell’s work will live on is that it illustrates one of the most important lessons in life: that friendship matters enormously, but that it is ephemeral, and that people slip in and out of our lives with amazing alacrity and often without reason. After the sixth volume of Dance came out in 1961 Evelyn Waugh wrote, as has been quoted in every review of this book because it is so brilliant:

The old magic works again . . . less original novelists tenaciously follow their protagonists. In the Music of Time we watch through the glass of a [fish]tank; one after another various specimens swim toward us; we see them clearly, then with a barely perceptible flick of fin or tail, they are off into the murk. That is how our encounters occur in real life. Friends and acquaintances approach or recede year by year . . . Their presence has no particular significance. It is recorded as part of the permeating and inebriating atmosphere of the haphazard which is the essence of Mr. Powell’s art.

When I first read these books I remember giving a sigh of relief; then I was young enough to think that all the people I had ever loved would be with me forever. And now, from the vantage point of greater age, I know how true these novels really are. And that haphazard quality is exactly what gives them their tension — when will so-and-so turn up again? And what has happened to him or her in the interim?

Much has been made of the character of Kenneth Widmerpool who is alternately obnoxious, pathetic, annoying, cruel, yet oddly magnetic. And there have been dozens of articles about who this or that character was in real life. But Spurling refuses to fall into that trap and, rightly, quotes Powell on a character from the Raj Quartet, “[he had] the slightly fleshless air of a character taken straight from life.” Most of Powell’s characters, even Nicholas Jenkins, who narrates these books and has been called Powell’s alter-ego, are fascinating amalgams of people he knew as he went through his life, listening and watching and letting it all simmer in his mind, then plunging into the hard and lonely life of getting it all down before showing each one, novel by novel, to his first reader, his wife Violet.

Much has been made of the character of Kenneth Widmerpool who is alternately obnoxious, pathetic, annoying, cruel, yet oddly magnetic. And there have been dozens of articles about who this or that character was in real life. But Spurling refuses to fall into that trap and, rightly, quotes Powell on a character from the Raj Quartet, “[he had] the slightly fleshless air of a character taken straight from life.” Most of Powell’s characters, even Nicholas Jenkins, who narrates these books and has been called Powell’s alter-ego, are fascinating amalgams of people he knew as he went through his life, listening and watching and letting it all simmer in his mind, then plunging into the hard and lonely life of getting it all down before showing each one, novel by novel, to his first reader, his wife Violet.

They are as interesting as the characters we know and love in Tolstoy, Stendhal, Balzac, and Proust; indeed, many critics have called Powell The English Proust. And for those of you who may think Powell and Dance are “too English, too full of the snobbery of 20th century English life,” it is interesting to note that Powell has also been called “the most European of the 20th century British novelists.” One of his great gifts was the balance he achieved between the personal and the historical, and for those who say that the series falls off a bit after the Second World War, well, so did life.

It is hard to write a biography of someone who spends most of his life at a desk or an easel. But that is what makes Spurling’s gift so remarkable. When I closed this beautifully researched and engaging book, I felt I had been enriched by getting to know this man who had such “an extraordinary grasp of what other people were like.” And who could write so sympathetically about them. Although Powell’s stock has gone down since he died in 2000, I hope that this new biography will spark interest in Dance and that these novels will be read once again with as much excitement as they generated when they first appeared.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and available on Amazon. The volume was among Kirkus Best of Indie of 2018. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Powell did not “love classical music.” IIRC he admitted to being virtually tone deaf, a trait that he gave to Jenkins.

Not everything in the novels is true. Jenkins may have been tone deaf, but according to Spurling, Powell was interested in art and music rather than sports and counted the composer Constant Lambert as one of his dearest friends.

Roberta Silman