Book Review: Thomas Bernhard — A Grouch of Greatness

“Whoever manages to write a pure comedy on his deathbed has achieved the ultimate success.”

— Thomas Bernhard

A biography examines, with mixed results, the life and work of Thomas Bernhard, an acclaimed Austrian writer and playwright his homeland loved to hate.

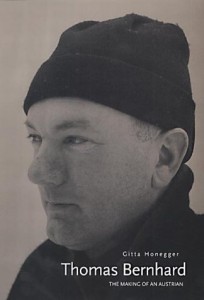

Thomas Bernhard: The Making of an Austrian by Gitta Honegger. Yale University Press, 348 pages.

Thomas Bernhard: The Making of an Austrian by Gitta Honegger. Yale University Press, 348 pages.

By Bill Marx

Thomas Bernhard hated his country and his country hated him back. European critics, however, acclaimed him the heir to Samuel Beckett and August Strindberg, so he was too valuable a cultural icon to be discarded. Hungry for international prestige, Austria let Bernhard toss the acid of his satire into its face until his death at the age of 58 in 1989. Bernhard’s obsessive target was the moral decay of postwar Austria, a land of “six and a half million retards and maniacs” whom he viewed as cheerfully anti-Semitic, thoroughly philistine, and determinedly bureaucratic. One of the major writers of the last century, Bernhard turned himself into a grouch of greatness, the magus of gall.

He adroitly exploited Austria’s masochism for dramatic purposes. Bernhard’s rare public interviews were occasions for colorful excoriations and insults. Even his will sent the country reeling — it stipulates that none of his plays be staged in his homeland for the next 75 years. But Bernhard is far more than the literary equivalent of the axe-murderer thumbing his nose at the sheepish bourgeoisie. His books tackle a crucial issue: how to depict the malignant legacy of the Holocaust without trivializing its horror.

At his best, Bernhard transforms his disdain at Austria’s hushed complicity with genocide, and the West’s ethical meltdown, into the rich and diverse art form of his 11 novels, five volumes of autobiography, and over 12 plays. His comedy is a sick, death’s head kind. His humor is a compendium of the demented and homicidal, the eccentric and inauthentic, that revels in outrage for the sake of a severe morality. Bernhard’s work suggests that epic disdain may be a more meaningful testament to the crimes of the past than well-intentioned homages to healing or the more passive hand wringing of the late W.G. Sebald.

Bernhard’s work invites revulsion rather than love, but that doesn’t make his comedies any less compelling, once you are ready for their challenging mix of high Modernism and low farce. His books are both celebrated and dismissed for their long, jerry-rigged sentences, monomaniacal repetitions, and uber-narcissistic male characters. The savage party-pooper in Woodcutters mutters a non-stop harangue of hate at the other guests, artists who swapped aesthetic ideals for economic pampering in postwar Austria. The book was banned in Austria because Bernhard modeled many of its characters on his contemporaries, but it became a best seller in Germany. Plays such as The Eve of Retirement focus on a family of aging, incestuous Nazis chortling over their power in contemporary Austria.

Bernhard’s fury isn’t monolithic. His five volume memoirs, published in English under the collective title Gathering Evidence, are a masterpiece of modulated reflection on a childhood spent amid the trauma of war. His novel Correction, which features a Wittgenstein-like philosopher at its enigmatic center, spins a brilliant variation on Thomas Mann’s Dr. Faustus. Bernhard’s fondness for disturbed and marginalized geniuses runs through The Loser, a fictional study of pianist Glenn Gould. Old Masters supplies moments of tenderness amid brittle reminiscences of a man for whom “there is no perfect picture, and there is no perfect book and there is no perfect piece of music.”

The inclination is to identify Bernhard with his usual protagonist – an aging egomaniac who spits out bile-filled riffs on issues such as social decay, art, health, and Austrian self-importance. In her biography (the first in English) Gitta Honegger, a professor in the Department of Languages and Literatures at Arizona State University, complicates the stereotype of Bernhard by portraying him as a misanthropic monster.

There’s no doubt Bernhard loved playing the ugly troll with a chip on his hunched shoulder. Born into a low middle class family, illegitimate, and most likely homosexual, he climbed up the social ladder by pressing readers’ faces in grime they didn’t want to see. He was not a nice person: he manipulated and abused his friends (particularly women), reveled in the rewards the despised establishment gave him, and let his appetite for media controversy mar his work, particularly his plays, which were often more effective as calculated scandals than as works of art.

Yet Honegger suggests Bernhard created an ornery persona in order to fend off compromise and survive fame: his infamous inhospitality was a form of protection. She also argues that self-hatred fueled his anger. She believes Bernhard, like the isolated figures in his plays and fiction, is “the survival artist as a virtuoso performance artist.” The writer’s inhuman persona was a game concocted to frighten the enemy, Austria. According to her, his books also dramatize the mechanics of posture, playing on the complexities of performance to diagnose and scold a culture the highest values of which had dissolved into acting out empty rituals.

Those who dismiss Bernhard as an opportunistic crank miss the point of his negative monochromatics. The rhetoric overkill is part of his vaudevillian stance. His manic monologists are infected with the very diseases they berate. Illness serves as a crucial and personal aspect of Bernhard’s critical vision. Because of a chronic lung condition, Bernhard was in and out of hospitals and sanitariums throughout his life. Unsurprisingly, his writing is infused with a sense of encroaching oblivion. Bernhard’s yakkers are demonic fools, avenging crab apples that are as much polluted products of the times as the hypocrites they condemn out of fear or a false sense of superiority. They use their tongues to ward off the grim reaper — that’s why they never shut up.

If only Honegger shared Bernhard’s sly sense of linguistic irony. Her book contains informative and insightful passages. The collection of Bernhard photographs are wonderful, including one of him holding a baby! Otherwise, the volume is too mired in academic thought to risk complexity or self-deprecating humor. Honegger’s sentences are clotted with impenetrable jargon, reductive psychoanalytic conjectures, and political correctness.

In the passage, “The tower’s interior evokes Plato’s cave in Luce Irigaray’s subversive scenario, where it is the excluded woman’s womb, the site of men’s captivity, the stage of their (symbolic) delusions and foreclosed desires,” Honegger uses feminist lingo as a club to hammer the patriarchal bully in Bernhard, into ideological submission. Bernhard, apparently, wasn’t the iconoclastic rebel he or his outraged readers thought he was. What’s ironic is that the kind of lingo Honegger uses in the above passage was the sort of intellectual myopia Bernhard laughed at with feverish bravado.

Honegger concludes that Bernhard, for all of his anger against society, “is as much activated by the constitutive grammar of authority as the culture he exposes and reaffirms with masochistic pleasure. Against the utopian notion of a theater that can change society Bernhard constructs a theater that brings out its reactionary resilience.” In other words, Bernhard is on the wrong side of the political divide — his moral critiques are problematic because they don’t come from the Left. It is unquestionable that Bernhard, like Swift and Celine, is part of an anti-utopian literary tradition that targets, among other things, the kind of earnest radicalism this biography champions.

Unfortunately, Bernhard fans will have to wait for a readable volume that sees him as a satirist who recognized he was part of the universal insanity. Only the beautiful and ferocious energy of his language sets him apart.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.