Visual Arts Review: “Living Objects — African American Puppetry,” Challenging Cultural Erasure

By Debra Cash

Playful and political, eerie and goofy by turns, this exhibition brings together puppets, performing objects, masks, and puppet (and doll) performances on video.

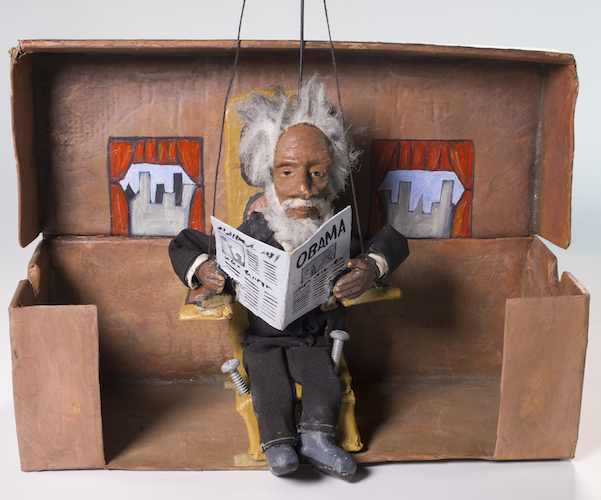

Frederick Douglass puppet in “Living Objects: African American Puppetry.” Photo: courtesy of the Ballard Museum.

Living Objects: African American Puppetry is at Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry, 1 Royce Circle, Suite 101B, at University of Connecticut in Storrs, until April 7, 2019. The museum is open Tuesday to Sunday 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. Admission is a suggested donation of $5.

An African-American ventriloquist’s dummy free to “put words in the white man’s mouth.” Faceless wooden jig dolls and an elaborately hatted Muppet-like church lady (“if you were going to be in the presence of the royalty — Jesus being the King of Kings — you should dress appropriately.”) Puppet portraits of Jackson 5-era and sequin-gloved Michael Jackson as marionettes. A video about Harriet Tubman portrayed by a Black Barbie. Rosie O’Donnell on TV, singing with an R&B quartet of dapper urban crows.

A prismatic exhibition, Living Objects: African American Puppetry at the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry in Storrs, CT, is a small exhibit that persuades by its sheer range. It shines a light on two dozen interstitial artists teetering between theatre and sculpture. Playful and political, eerie and goofy by turns, this exhibition brings together puppets, performing objects, masks, and puppet (and doll) performances on video. Whether these puppets and their settings are made of cardboard and shower curtains or foam molded to exacting and replicable commercial specifications, designed for one-off special occasions or as recurring characters, the exhibit combines whimsy and pointed social critique.

Co-curated by Atlanta-based scholar and animatronic puppeteer Paulette Richards and Ballard Museum Director John Bell, the exhibit offers this explanation: “since their arrival in the Americas, African people have animated objects in a rich variety of forms and contexts. Despite the prohibition by slaveholders on the creation of figurative objects reflecting an African-derived worldview, African Americans nevertheless animated objects to represent their experiences and identity.”

Living Objects is tidily displayed in a pair of perpendicular rooms, and organized somewhat randomly into overlapping themes (many of these puppets could easily be slotted into, for instance either “Puppetry in Storytelling” and “Puppetry as Craftsmanship.”) Most visitors to the exhibit are unlikely to be familiar with historic artists like Ralph Chessé, who opened a puppet theatre in San Francisco in 1929. His creation, Brother Buzz — the elf turned into a bee, with spats and top hat — found fame as the titular head of the longest running children’s program (1952-1969) in the history of San Francisco television. At Ballard, Brother Buzz and his pal Mr. Robin Redbreast are instantly identifiable as exemplars of black dandyism.

Two contemporary artists are familiar names. Living Objects includes the elaborately beaded, fabric stuffed mask that was Faith Ringgold’s response to her first trip to Africa, and a pair of papier-mâché hand puppets that William Pope L. (whose other artistic productions have brought him to places like the Whitney Bienniale and Boston’s ICA) created for a video about Civil War reenactors. Most, however, will be new. Baltimore-based String Theory Theatre, a company made up of artist Dirk Joseph and his teen-aged daughters Sequoia and Azaria is represented by a trio of shadow puppets and in a gallery setting, those black silhouettes echo Kara Walker’s sardonic silhouettes of violence and sexual debasement. The story does too: this 2016 production was a satirical narrative about the dethroning of the “tyrannical leader of the free world.” (If only!)

One of the exhibits in “Living Objects: African American Puppetry.” Photo: Debra Cash.

There is specificity and beauty in the puppets made for “Obama Express 1 & 2” by the Puerto Rican activists of Papel Machete. Sized for a tabletop, Frederick Douglass sits along train tracks waiting for, and protesting, the pre-inauguration train ride Barack Obama is taking to Washington D.C. In a sequel to that 2009 show, Frederick Douglass and Mumia Abu-Jamal go down to Ferguson to protest the shooting of Michael Brown. The puppet show plots are often labyrinthine, and if I have a quibble, I would have loved to have been able to see at least excerpts of these puppets in motion.

My personal bias as a dance insider notwithstanding, who could resist the clasped hands and placid expressions of Pandora Gestelum’s African-American jazz dancer marionettes? With something of the flair of Frank Ballard’s famous pair of Fred and Ginger marionettes housed in the museum’s permanent collection, Gestelum, who is based in New Orleans’ 9th ward, offers a vision of a strange episode in 1919 when an axe murderer required that “the citizens of New Orleans all dance to jazz music throughout St. Joseph’s night, or face bloody reprisals. Across the city, people of all colors, classes, and inclinations danced the night away, to keep the Axeman from the door. The music that so many had feared would corrupt their souls, would now serve to save their necks. ” I’m fascinated by the artist’s fraught multiracial history and her statement:

We are devoted residents of the Gulf Coast and feel connected to our community through our common experience of reinvention. Displaced from our preexistent positions within “city,” “home,” and “family”, our questions of self-identification are fundamental: What is it that we were and what will we become? We are exploring, through puppetcraft and performance, the creative capacity of dispossession — the way that radical shifts in belonging reinvent being.

Brad Brewer, founder of New York’s Brewery Puppet Troupe, was a child ventriloquist in the Soundview projects in the Bronx doing birthday parties, performances for his mother’s friends, and mashups like “Little Red Riding Hood Meets Godzilla” — and acquiring about 100 puppets by the age of 10 — until he gave up puppets for basketball and girls as a young teen. But he returned to puppetry as a student at the Pratt Institute of Art. His guide was Kermit Love, the Santa-look-alike who moved between theatrical design and puppetry, and who realized puppeteering immortality by co-creating Big Bird and Mr. Snuffleupagus for Sesame Street.

Brewer went on to collaborate with Jim Henson (he worked on the Muppets Take Manhattan team); in 1996, Mister Rogers returned a knitted scarf to one of Mr. Brewer’s puppets, which made the puppet feel “brave and strong.” If I were that puppet, I would never take it off.

Last week, on hand for a lecture at the Ballard, Brewer shared that he became a street puppeteer unexpectedly. Creating shows like “The Jackson 5 Meet Malcolm X,” he was committed to sending a message of uplift, and giving African-American historical figures the Great Man treatment usually found in horatory movies like Young Mr. Lincoln. (His puppet of African-American inventor Lewis Latimer, along with one he made of Frederick Douglass and another of Thomas Edison are now in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian.)

Two of the exhibits in “Living Objects: African American Puppetry.” Photo: Debra Cash.

The Crowtations, modeled on Motown royalty, were originally part of a Harriet Tubman show in which the singers guided her along the Underground Railroad to freedom. To promote it, the four black men who manipulated Otis, John Jay, Fast Eddie, and Junior took the Crows into Central Park. The New York Times caught their act, and soon they were bona fide stars, opening for David Brenner and Cyndi Lauper, appearing in nightclubs, and starring in a Coke commercial (which you can see on a loop at the Ballard exhibit).

Brooklyn based puppeteer and children’s book author Nehprii Amenii, a generation younger than Brewer, is represented in the Living Objects exhibit by both the largest and smallest puppet on display. Standing almost ten feet tall, her papier-mâché “Tribute to Judith Jamison” was created with the children of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s AileyCamp in 2010. Dressed in the white costume of Ailey’s 1971 Cry, Jamison’s skirt became the screen for a shadow puppet show where the children displayed symbols — flowers, sunbursts — of how she had inspired them to shine. Moving down the scale, Amenii has constructed a tumbledown cardboard house toy theatre standing on the base of a record turntable. Her tiny father puppet is made of wine corks, a metonym for his alcoholism.

“Who has time to do something so trivial as to play with dolls?” Amenii quipped. Her thesis project at Sarah Lawrence, “Food for the Gods,” addresses black men and police violence; the puppets are deconstructed with only a lifelike mask, a hand, and a chair evoking a whole person. Like the exhibition Living Objects, this is work that challenges cultural erasure.

Coming Up: Living Objects Symposium and Festival at the Ballard Institute Feb. 7-10, 2019, which will bring together scholars, performers, students, and the general public to discuss, watch, contemplate, and enjoy the many different aspects of African American puppetry. This project is presented as part of the African Diaspora, an initiative organized by the UConn School of Fine Arts, which celebrates the 50th Anniversary of the UConn African American Cultural Center.

Debra Cash, a founding contributor to the Arts Fuse now serving on its Board, is Executive Director of Boston Dance Alliance.

Tagged: Ballard Institute, John Bell, Living Objects: African American Puppetry