Book Review: “Love in the New Millennium” — Inscrutable Passion

By Katharine Coldiron

This is a bewildering, frustrating, deeply weird novel, densely written and remarkably free of signposts.

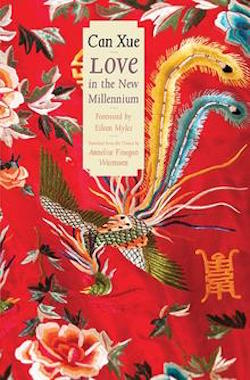

Love in the New Millennium by Can Xue. Translation by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen. Yale University Press, $25.00, 256 pages.

Eminent poet Eileen Myles, in their forward to Love in the New Millennium, calls the book “very boring, as a plotless book is. A circling non-building narrative gets tiring. What’s the pleasure, then? Humor and surprise.” Myles is narrating their own reading experience, but theirs is probably not going to be the universal response this novel. For many readers, the tiring aspects of Love in the New Millennium may become overwhelm ing, to the point where the the experience supplies no pleasure at all. It’s a bewildering, frustrating, deeply weird novel, densely written and remarkably free of signposts. So, despite its excellent pedigree, even enthusiasts of international literature can be forgiven for passing on it.

The book’s author, Can Xue, is “widely considered the most important novelist working in China today,” according to its back cover, and its translator, Annelise Finegan Wasmoen, is an award-winning translator of Chinese works, including Xue’s The Last Lover. But it’s still a challenging piece of literature to decipher, even on the most basic levels. Each chapter of the book is narrated by different characters, usually one or two. Each figure is loosely connected to the next, and the book forms a rough semicircle, chapter by chapter. What connects these characters is love — or, mostly, sex, which sometimes leads to love; thus the book’s title. The plot structure is almost picaresque, moving from one minor encounter to another without causality or even meaningful patterns. But what it really resembles is a dream. The security and confidence in a dream state of here is what happens next, even if the ensuing events make no sense and aren’t predicated on what came before, is an experience that’s almost miraculously caught to this book. But, then, in the wrong hands, dream narration is dreadful — meaningless and impermanent.

If not the plot, one should reasonably be able retain information about the characters: bawdy Long Sixiang, nervous Wei Bo, beautiful A Si, uncanny Dr. Liu, yearning Cuilan. They seem to be worthy enough, but there are so many, and they are as faceless and changeable as figures in a dream. No one gets a significant physical description. Plus, the book’s constant, restless motion pushes the reader further and further on, into another character’s narration and struggle, before she has really gotten the measure of the protagonist in the prior chapter. Love, mainly coupling and decoupling, moves the plot. Though there are a few major points that the book’s timeline circles: Wei Bo voluntarily going to prison, Xiao Yuan visiting Nest County, and various female characters going to work at a hot springs, where they prostitute themselves. But love doesn’t really stick among the characters, nor do these figures or the plot stick for long inside of a reader’s mind.

Acclaimed Chinese author Can Xue — her novel is seeded thoroughly with self-obfuscation. Photo: wiki common

A consistent theme is the dissolved boundary between life and death, and between waking and sleeping. (Characters sleep a lot in this book.) In Nest County, which comes off as a kind of paradise, death and sleep are almost indistinguishable. Death is not exactly permanent; a man with a white beard dies and reappears in the narrative at least twice. Additionally, flowers and growing things populate Nest County much more prominently than in other parts of the narrative. “In Nest County,” a minor character tells Xiao Yuan, “your thoughts turn into reality.” It’s unclear where any of this is geographically, which is typical of Love in the New Millennium. Thoughts may become reality, but reality is extremely fuzzy.

None of the above communicates how strange the novel is. It’s baffling, more often than not. A short scene from one of Wei Bo’s chapters:

“Long Hair wants you to go back to see your hometown. Why haven’t you gone yet?” he asked.

Wei Bo noticed the fluency of his speech. Apparently he wasn’t a drunk.

“I need to find out where my hometown is,” Wei Bo said.

“Huh, your lot are always like this. I know your type. Are you a government employee?”

“I’m not. I sell bamboo cooling mats.”

“That’s the same thing. I know your style. This isn’t the place for you. When it’s light you should go. Listen to what Long Hair says. Go back to see your hometown.”

I can offer no context from the surrounding chapter that will give this scene more sense than it has in the excerpt. And the novel is filled with moments like this — in fact, more of them than moments that resemble normal interactions. More often than not, this is a bizarre and difficult book, seeded thoroughly with self-obfuscation. Much of the dialogue feels unnecessarily blunt and robotic. For example, from Xiao Yuan’s chapter: “You’re very interesting. I share your point of view. Every object has secret purposes. What I mean is, life is in and of itself inspiring.” This may be a translation problem — the obstacle of rendering an experimental Chinese novel in English may have proved too much for Wasmoen, despite her experience and expertise — or it may be simply Xue’s style.

Love in the New Millennium is not an obviously experimental novel. Its language is simple, its narrative is relatively linear, and its loose dream-state nature doesn’t present an evident barrier to reader comprehension. But these factors make the experience of reading the book all the more destabilizing. This shouldn’t be so hard, the reader might mutter to herself. But it is so hard. It’s a wholly exasperating book, and its surreal charms are not rewarding enough to rescue it.

Katharine Coldiron‘s work has appeared in Ms., the Guardian, the Rumpus, and elsewhere. She lives in California and blogs at the Fictator.

Tagged: Annelise Finegan Wasmoen, Can-Xue, Chinese Fiction, Love in the New Millennium