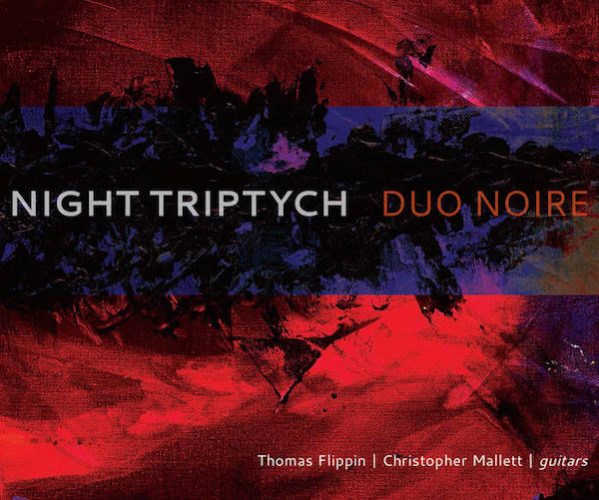

Classical CD Reviews: Duo Noire’s “Night Triptych,” Justin Taylor’s “Continuum,” and Brahms’ “Ein deutsches Requiem”

Night Triptych is an important disc, but also an inviting one that takes you to some fresh places well worth experiencing. Also, another success for harpsichordist Justin Taylor, and a well-earned one at that.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Duo Noire’s album Night Triptych (on New Focus Recordings) checks off a number of socially-relevant and politically-charged boxes. Given that it’s an album made by a pair of African-American guitarists — Thomas Flippin and Christopher Mallett — playing music by six women composers born since 1978, three of whom hail, one way or another, from the Middle East, how could it not?

Not to worry, though: Night Triptych isn’t just an exercise in musico-political activism (though, in a few ways, it’s a great example of that). Rather, its first strengths rest precisely where they should: in the music and the sheer excellence of the performances that catch the ear and don’t let it go.

Clarice Assad’s Hocus Pocus, for one, channels humor and mystery with some beguiling sonic textures over its three movements (“Abracadabra!,” “Shamans,” and “Klutzy Witches”). Her fluency writing for the ensemble is always striking, especially in the brilliantly flexible finale.

Mary Kouyoumdjian’s Byblos draws on the composer’s Lebanese-Armenian heritage, seeming to evoke the imagined sounds and gestures of ancient Lebanese folk music. Its mix of mystery and tough, dancing energy is beautifully – and hauntingly – executed.

Courtney Bryan’s Soli Deo Gloria offers a similar blend of focused devotion and explosive energy.

As in the Kouyoumdjian, Golfam Khayam’s title track draws on Middle Eastern ethnic music (in this case from the composer’s native Iran), as well as numerous contemporary Western extended techniques. Sensuous flourishes mark the dolorous opening “Improvisatory” while violent figures explode across the central “Quasi Furioso.” The finale, though, brings the work to a tender, lyrical close.

Gity Razaz is the album’s other Iran-born composer. Her Four Haikus are a set of touching miniatures: lushly scored and impassioned over the first three, playful in the concluding fourth.

Gabriella Smith’s Loop the Fractal Hold of Rain wraps up the album in a blaze of excitement with wild, looped glissandos giving way to folk-like refrains and tangy, bent-note figures before eliding into a surprisingly moving coda.

Mallett and Flippin play the whole program with terrific panache. Indeed, it would be hard to imagine more engaged or sympathetic performances of any of these pieces and the guitarists’ command of the varied stylistic demands between all six is faultless. An important disc, sure, but, even more, an inviting one that takes you to some fresh places well worth experiencing.

There’s something highly appropriate about pairing the music of Domenico Scarlatti with that of György Ligeti. Both were visionary composers with penchants for doing unexpected things with pretty much anything that might be considered conventional (or not). Justin Taylor’s new album, Continuum (on Alpha), gamely showcases harpsichord pieces by each.

The results are predictably fresh and lively.

Take any of the dozen Scarlatti sonatas on offer here. The D-major (K. 141), for instance, with its abrupt pauses, thudding dissonances, and obsessively-repeated figures sounds hardly like it belongs to the 18th century. Neither does the A-major (K. 208), with its spare, chromatic textures and pungent harmonic progressions.

In fact, they all have more in common with three Ligeti selections (the title track, Passacaglia Ungherese, and Hungarian Rock) than you might, at first glance, expect. Ligeti often toyed with archaic forms (the passacaglia, in particular) and their main features are nearly always clearly evident. Here, they fit with the Scarlatti selections because of these allusions but suggest a logical outworking of the older composer’s more eccentric tendencies; Ligeti, then, is clearly part of a long tradition (even as some of the best of his music seems to come out of nowhere).

Taylor, whose previous all-French album I loved, gives commanding performances of all the pieces he chose. The Ligeti scores are remarkably crisp and clean-textured (Hungarian Rock is a true riot), while the Scarlatti works are impeccably voiced and brim with charm. Technically, his playing is faultless – just listen to the evenness of his voicings in the Scarlatti F-minor Sonata (K. 239) or the rhythmic layering of Ligeti’s Continuum – and, expressively, they’re enchanting. Another success for Taylor, then, and a well-earned one at that.

What’s there to say of this new arrangement (by Iain Farrington) of Brahms’s evergreen Ein deutsches Requiem?

On the plus side, in the hands and voices of the Yale Schola Cantorum, this is a focused, personal account of one of Brahms’s most intimate and devastating scores. The choral singing’s superb and, as far as this Hyperion recording goes, there’s much to be said for the emotional directness of the outer choruses and “Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen” in this reduced setting.

At the same time, it’s hard to get away from the impression of scrawniness emitted by this abbreviation of Brahms’s orchestra to a small group of winds, strings, and piano leaves. Yes, it’s inspired by Brahms’s own piano four-hands reduction and, I suppose, such a thing fits the requirement of a small choral group that is looking for more than a keyboard to accompany this much-loved work.

Even so, the Requiem’s big moments – like the second movement’s “Die Erlöseten des Herrn” and the third’s “Die Gerechten Seelen sind in Gottes hand” – all sound paltry and lacking in needed (instrumental) body. One misses the original’s lovely coloristic touches (like the harp writing in the “Selig sind, die da Leid tragen”). And, while there are notable benefits to clearing out accompanimental textures (Brahms’s vigorous contrapuntal writing in the second and sixth movements do come across with welcome clarity and energy), they ultimately don’t compensate for what’s lost in the process of instrumental elimination.

That said, conductor David Hill’s tempos are well judged and the level of performance on display, both choral and instrumental, is generally quite high. Soprano Natasha Schnur sings a lovely “Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit.” Baritone Matt Sullivan is paler, tonally, but his solos in “Herr, lehre doch mich” and “Denn wir haben hier” are suitably vulnerable.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Alpha, Duo Noire, Ein deutsches Requiem, Hyperion, Justin Taylor. Continuum, New Focus Recordings