Music Feature: Toots & The Maytals — Cranking and Skanking in Worcester

Toots Hibbert’s voice expresses both his Jamaican country church upbringing and his deep love of American R&B and soul.

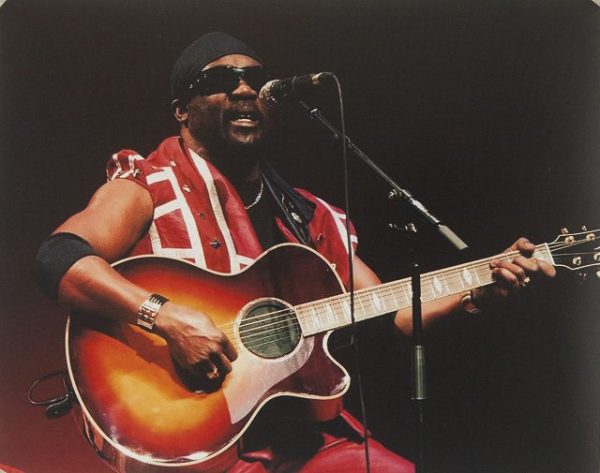

Reggae legend Toots Hibbert — still going strong at 75. Photo: Royal Vision.

By Noah Schaffer

Nearly 40 years ago Toots Hibbert, already a reggae veteran, recorded a song called “Never Get Weary” with his group the Maytals. The song was about resilience in the face of oppression and colonialism. Then and now it could also apply to Toots himself, who continues a nonstop touring schedule at 75.

Hibbert’s voice expresses both his Jamaican country church upbringing and his deep love of American R&B and soul. His songwriting reflects this passion in both cunning and thoughtful ways. The original Maytals were a vocal group churning out ska hits at Studio One with the backing of the Skatalites. They remained at the top of the charts when ska developed into rock steady and then reggae, thanks to such songs as “Monkey Man,” “Pressure Drop,” and “54-46 (That’s My Number).” A contract with Island Records and his songs in the Harder They Come soundtrack solidified the group’s international following. After the vocal group split in the early ’80s, Toots retained the Maytals name. In 1989 he recorded the beloved Toots in Memphis album, which found him paired with some of Memphis soul’s finest session players.

Toots’s career came to a screeching halt in 2013 when, while performing, he was hit by a bottle of vodka thrown by a concertgoer. Three years later he returned to touring and hasn’t let up since. Incredibly, his band still includes such key Jamaican musicians as bassist Jackie Jackson, drummer Paul Douglas, and guitarist Rad Bryan.

Toots will supply a heavy dose of authenticity to the inaugural ska-oriented Cranking and Skanking Festival — which takes place outside the Worcester Palladium on Saturday, August 25. The lineup includes the headliners Mighty Mighty Bosstones, Fishbone, and a slew of others.

Recently, Toots spoke with the Arts Fuse from a Toronto tour stop. He discussed his influences and also revealed that an oft-repeated origin story behind one of his biggest hits is partly a myth.

The Arts Fuse: I’d like to start with your gospel roots. Can you explain what the Jamaican Revival and Pocomania churches were and how they influenced you?

Toots Hibbert: Well, it is a church — it’s a regular church where people go and sing and clap their hands and, you know, praise God. The Pocomania church — yeah I grew up in a church like that, in the country, and I also grew up with the Rastafari church.

AF: And those church roots are still evident in your live shows — frequently you’ll begin a song the way it was on the record before speeding it up and offering a real revival ending.

Hibbert: I keep on doing that because that’s my roots, you know. And I have to sing happy songs to keep people happy, and have happy rhythms, and just take it to a different level for the audience. From the beginning, in 1964, I started doing that. I have continued to develop that approach for performing for my audience. I intend to keep doing it — I don’t stop! That’s why every night I play — anywhere –I get a full house no matter what — a full house every time.

AF: Who inspired you to start playing guitar?

Hibbert: Well, when I was much younger I made a four string ukulele. I taught myself by watching other people play their instruments. I said that I wanted to be a musician, not become a boxer. I had been boxing at school. People started to tell me I can sing, they like how my voice sounded. I continued to play my guitar and practice. I’m not really a great guitar player, I just create sounds. I’m a creator and a composer. I’m not an accomplished guitarist, but people call me great. So I eventually decided to sing with my guitar instead of going into boxing; also, I used to make money by barbering, cutting hair. People kept telling me I could sing and they believed in me so I said “all right.” My father and mother could sing, my sister and brother could sing, but they sang in church. I decided to sing secular music — just to make life better.

AF: Can you talk about some of your favorite songwriters, and what you think makes for a good song?

Hibbert: Well, I used to listen to Wilson Pickett, I listen to Ray Charles, Otis Redding, Elvis Presley, James Brown — a lot of good people. I was so sorry when [Fats Domino] died. I sing “Let the Four Winds Blow.” I loved his music. I like the way that, in those days, it was not a long song, two minute, three minute, and it always be a good song and a number one song all over the world from all these great singers. But nowadays people sing songs for four minutes, five minutes; they are very long. I have some long ones on my albums, but I grew up listening to great singers that just wrote a few lines. That’s the way I learned and that’s what I prefer.

Toots Hibbert in action. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

AF: Seeing that “54-46” is about the prisoner number you were given the time you went to jail for marijuana, I’m curious what you think of the efforts for legalization.

Hibbert: I don’t smoke! It was politics. I came from the country, and other musicians and people were jealous. I had 31 number one records on Jamaican radio. There was a program called “Festival” — if you write a good song for the show you would be recognized as a star in the music. I wrote a song called “Bam Bam” — it was a “Festival” winner. People questioned my success, other artists begrudged me. But I never smoked. I just live cool for a while.

So I spent about eight months, not in jail, but in a place that I could go home. They give me my guitar. I never work in those places, I never have a number, I have a dinner — my wife take it for me. [Island Records owner] Chris Blackwell came to Jamaica and was going to arrange a tour of the UK for the first time, but when [they] did that [detention] for me and Blackwell took someone else in my place — it was a bad thing they done to me, so I wrote a song about it. Because I don’t call it prison; when you go to prison you have to have a number, get clothes, go to work, do all kind of stuff. They give me a big room for myself and give me my clothes from my home. I was framed. They framed me — I never smoked — but when I finished and I come and sing the song “54-46” I just created it, because I’m a songwriter, and people believed that it is my prison number. Some people said it was my bike number — but I just created it! And the song became number one.

AF: We’re just about out of time, but I was wondering if you’ve recorded any new material since you returned to the music scene.

Hibbert: Yes, and I am going to release a new single from the album, called “Marley.” I wrote it about Bob Marley; he was my good friend. I came to Kingston, to Trenchtown, in ’64 and he started in ’62. So we met each other in Trenchtown — Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh, and some other singers, such as Joe Higgs.

AF: And you were one of the first reggae artists to tour Africa when you traveled there with Marley.

Hibbert: I remember going to Nigeria and the Ivory Coast. I would go on stage at 5 p.m. and never come off until the next morning, 6 a.m.! And the people, they still wanted more!

AF: Thanks again for your time.

Hibbert: All my friends can look for Toots and the Maytals. We will give an equal share, all you got to do is prepare!

Over the past 15 years Noah Schaffer has written about otherwise unheralded musicians from the worlds of gospel, jazz, blues, Latin, African, reggae, Middle Eastern music, klezmer, polka and far beyond. He has won over ten awards from the New England Newspaper and Press Association.

Hi Paul Douglas,

The wonderful drummer for the Toots and the Maytals band. Toots is himself a

legend within the reggae genera and it is just fantastic that he is still being such

a creative force on this journey of music. I am from the same generation as this band and their music still gives me the right vibes.I hope I am not just stuck in my musical appreciation of just our era,but what the current artists are doing does not pull me in. If I am a minority then this opinion does not matter.

Having said that,you guys are just the best,

Richard”Von”White