Theater Review: “We The People,” “The Member of the Wedding,” and “Creditors”

Three theaters in the Berkshires offer differing views of the past.

Roslyn Ruff (Berenice) and Tavi Gevinson (Frankie) in the Williamstown Theatre Festival production of “The Member of the Wedding.” Photo: Daniel Rader.

The Member of the Wedding by Carson McCullers. Directed by Gaye Taylor Upchurch. Staged by Williamstown Theatre Festival on its MainStage, Williamstown, MA, through August 19.

We The People, Double Edge Theatre’s Summer Spectacle, written and performed by Double Edge Theatre, Ashfield, MA, through August 19.

Creditors by August Strindberg, adaptation by David Greig. Directed by Nicole Ricciardi. Staged by Shakespeare & Company in the Elayne P. Bernstein Theatre, Lenox, MA, closed.

By Bill Marx

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” runs one of William Faulkner’s oft-quoted lines. But how does the past live on? And what methods work best at keeping it hale and hearty? In my trip to theater in the Berkshires over the past weekend I received three different answers.

In Double Edge Theatre’s production of We The People, history is reinvigorated via an eye-filling look at the lives and ideas of quartet of Massachusetts-born activists (Lucy Stone, W.E.B Du Bois, Samuel Nightingale, and Henry S. Ranney). At the Williamstown Theater Festival, Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding (1950) ends up flattened by a production that overemphasizes the play’s depiction of race in the South during the ’40s. Finally, Shakespeare & Company wrapped up its splendid production of August Strindberg’s Creditors, a lesson in dramatizing psychological warfare between the sexes from a master. Over the years, I remember seeing far too many potted Shakespeare & Company adaptations of Edith Wharton’s short stories. They were bread knives compared to Strindberg’s switch blade, which director and cast made sure has remained sharp after 120 years.

I don’t have much to add to the Arts Fuse review of Creditors, though I disagree that, as the husband out to punish his former wife, Jonathan Epstein is the devil incarnate. Yes, he makes use of his suave voice to purr, hector, and command an insecure second husband into abject haplessness. There is never a question that the guy is a vampire, sucking the life force out of his victim. But, underneath the ubermensch bully, Epstein suggested an undercurrent of genuine feeling — humiliation, regret for lost love, loneliness. Yes, there is a touch of Iago in how the character collects on what he believes his former wife owes him (cue accusations of the dramatist’s misogngy). But the actor indicated that there was a human being trapped inside the machinery of revenge. Strindberg understood that the Darwinian survival of the strongest makes life hell for the winners as well as the losers. A point that should be kept in mind in the age of Trump.

I saw The Member of the Wedding with the hosannas of Ben Brantley’s NYTimes review floating through my mind. (WTF sent out an e-mail blast festooned with his blurbs.) For the critic, “the center of a classic play has definitely shifted” with this production. No longer, in director Gaye Taylor Upchurch’s interpretation, is it the “Frankie Addams Show,” starring a 12 year old outcast desperate to be free of home, latching onto her brother’s upcoming wedding as a way to escape a stifling Georgia town and her radical uncertainties about herself. No, now it has become the story of Berenice Sadie Brown — the African-American housekeeper, protector of lost souls — and life in the Jim Crow South. There is that element in the 1948 novel and the 1950 play — though McCullers’ interest in civil rights became much stronger in her later novels and stories.

Of course, once you minimize Frankie in a script that is not a ‘classic’ — this is a lyrical but lumpy ’40s talkfest in which nothing much happens — you are going to have problems maintaining dramatic focus. For Harold Clurman, the original Broadway director (and who was no slouch as a critic), the script’s spine is the search for “connection” in the face of overwhelming loneliness. Frankie, Berenice, and young John Henry West create a space for intimacy in a gray and airless environment. The Member of the Wedding is not just about Frankie (or it shouldn’t be): it is about the rise and eventual fall of a fragile world that the trio of characters share, a nurturing bond that is under continual threat — by racism, yes, but also mortality, indifference, and unkindness. (Tennessee Williams was an admirer and friend of McCullers.)

By highlighting Berenice’s disconnection, the scenes in this production between the kids and their minder come off as emotionally hollow. An affectionate link isn’t established between Frankie and Berenice, particularly given Tavi Gevinson’s strident tomboy. (A number of the supporting performances are also weak; some of the actors swallow their words.) When Frankie’s father calls a black man a nigger in the kitchen, in front of his daughter, McCullers doesn’t give her a line of protest. In the context of Upchurch’s interpretation, it suggests that Frankie may be just another racist, of the self-involved variety. Why is the play dealing with the irritating narcissist rather than with the heroic/stoic Berenice? The director seems to share this impatience with Frankie: the scenes featuring the housekeeper and the other black characters have a vigor missing elsewhere in the staging. Roslyn Ruff’s Berenice is a sturdy portrait of long-suffering disappointment, but it doesn’t escape cliche.

The delicate power of The Member of the Wedding depends on maintaining McCullers’ balance among her trio of ‘outsiders.’ It is not about pushing one character or another ‘center stage’ — no matter how “heartbreakingly prophetic” she may be. And that choice leaves this WTF production lopsided, unsatisfying, and far from definitive.

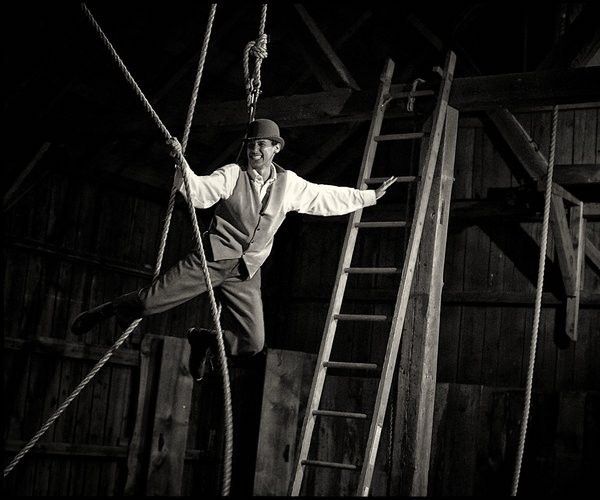

Travis Coe in a scene from Double Edge Theatre’s production of “We The People.” Photo: Bill Hughes.

We The People is a surrealistic hymn (designed, directed, and designed by Stacy Klein) to a quartet of real life local heroes. It is staged over a bucolic hunk of the Double Edge Theatre’s 100 acre property in Ashfield, MA. Lucy Stone (Jennifer Johnson) was a prominent U.S. orator, abolitionist, suffragist, and a vocal advocate and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, she became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a college degree. Henry S. Ranney (Matthew Gassman)’s family owned the Double Edge Theatre property starting in 1796. He was a member of the Liberty Party, an abolitionist group. Celebrated African-American author W.E.B. Du Bois (Travis Coe) co-founded the NAACP and was a civil rights activist. Samuel Nightingale (Adam Bright) was “known in the 18th century as the Wizard of Bellus Road. He refused to be buried in the Ashfield churchyard.” A fictional representative of the working class is tossed in for salt-of-the-earth measure: Guiseppe the Cobbler (Carlos Uriona), “a character of Italian-Argentine descent, based on the US census in Pittsfield.”

The opening scenes, in which small groups listen to the characters tell us about their struggles and hopes, smacks at times of potted re-creations of history for tourists — though W.E.B Du Bois’ wild fable, in which actors do battle on stilts, forecasts the unconventionality to come. The evening takes off when we move into the second floor of the space’s barn, when the characters — jumping, orating, scaling the walls, hanging from ropes — create a swirling (and at times confusing) palimpsest of desires, memories, and regrets. And the proceedings truly soar once we move out into on the pond on the grounds, as some of the figures take a dip (or flying leap) in the water.

Double Edge Theatre is making political points, of course, about how past dissent should inspire the present. But it does so by exploring a theater that draws on the power of space, creating different perspectives by placing the audience in various locations and natural settings. The attractions of this production are rooted in its creation of beautiful and/or compelling images: a ghostly figure on stilts glimpsed gamboling in a darkening background, Shaker women dancing out in the fields, Bright’s Nightingale, a Thoreau gone-ga-ga, setting fire to parts of his hermit’s tower. Live performances of American folk music and the ethereal warbling of Amanda Miller’s “Songbird” also add to the spell.

Brantley finds relevance in an up-to-date re-think of The Member of the Wedding, but Double Edge Theatre is presenting theater that speaks more directly to our times: this is not an athletic spectacle for its own sake (Cirque du Soleil), but energized by the Greeks and their interest on connecting theater with community and the possibilities of civic action. Here’s a few lines from my latest e-mail from Bill McKibben about how we can take on climate change:

But the biggest thing that anyone can do to fight climate change is to become a little less of an individual. Individually, we can reduce each of our carbon footprints slightly. Individually, we can use less electricity and not rely on fossil fuels… But together, we can save the planet.

We The People represents a kind of theater that is less about celebrating our individuality (‘We can all be heroes’) and more about stimulating our deep need, as a collective, to hallucinate ways in which society can move forward. “In Dreams Begin Responsibility” wrote Delmore Schwartz. Double Edge Theatre offers one way the stage can use the past — to speculate about the creation of an alternative future.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Thanks! There is an error in the Double Edge Theater location at the top of the article: should be “Ashfield”, not “Ashland.”

Also, I would quibble with giving their location as the Berkshires, as they are a good deal east of Williamstown/Lee/Lenox and located in Franklin County.

Fixed the location — thanks. I take your point. I may have been taking editorial liberties in terms of the location. Wanted to talk about a Berkshires round-up.