Theater Preview: Homage to Federico García Lorca

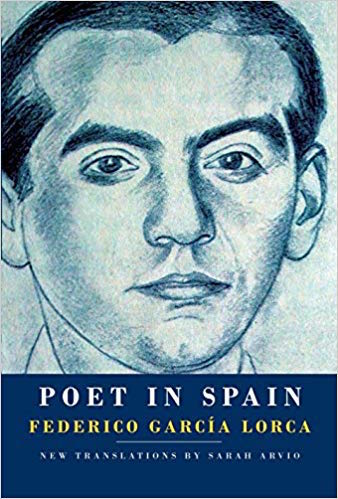

A newly published book of translations and two upcoming Boston-area stage productions confirms the enduring poetic power of Federico García Lorca.

Poet and dramatist Federico García Lorca — “his work has to sing on stage.”

By Robert Israel

In Poet in Spain, her new translations of selections from the works of Federico García Lorca (1898-1936), poet and essayist Sarah Arvio marvels how, in the 80 years since Lorca’s murder by fascists during the Spanish Civil War, the poet and dramatist’s popularity in Spain — and globally — has soared.

“Lorca is constantly in the Spanish news; he is a subject in himself, like the presidency or the economy or the weather,” Arvio observed in an interview. “The reason the world cares what happened to him is that he wrote — for us — something original, profoundly beautiful, lyrical and essential.”

Lorca’s popularity transcends cultural frontiers, as audiences in the Boston area will soon discover with the staging of two new adaptations of his plays: Doña Rosita the Spinster and Yerma. (More about these in a moment.)

But first: What is it about Lorca’s work that commands such on international interest? Arvio has an explanation: “[Lorca’s] descriptions of human desire, oppression and suffering are cloaked in a language so lovely that you hardly notice the social criticism, the compassion for oppressed people, the belief in sexual liberty.”

The late American poet Philip Levine, working third-shift on an automobile assembly line in Detroit, credited Lorca with waking him from his torpor: “As I stood in the stacks of the Wayne University library,” Levine wrote in his autobiographical The Bread of Time, “my hands trembling, [I] read my life in his words…How could this strange Andalusian, later murdered by his countrymen, come to understand my life, how had he mastered the language of my rage?”

Across the border, Canadian poet/songwriter Leonard Cohen (who later named his daughter Lorca), had an epiphany reading the poet in a Montreal bookshop: “His poems perhaps have had the greatest influence on my texts,” Cohen wrote. “He summoned up a world where I felt at home… A few years ago, I wrote a musical adaptation of Lorca’s ‘Little Viennese Waltz.’ … Lorca is one of those rare poets with whom you can stay in love for life.”

Lorca poeticizes the elemental conflicts within the human condition in a stirring, rich voice – one moment strident, the next rhapsodic — a linguistic bounty that the two upcoming productions planned for the Boston area will surely draw on.

Boston playwright Melinda Lopez began her translation of Lorca’s Yerma more than five years ago. The American Conservatory Theater (ACT) in San Francisco had initially commissioned the work but, due to a change in artistic management, ACT backed out of the contract. Boston’s Huntington Theatre Company stepped up and has committed to stage a full production of Yerma in spring 2019. (Lopez, also known to Boston audiences as an actress, will not perform in the production.)

“Lorca’s work is incredibly deep,” Lopez said in an interview, “making it difficult to translate. A translator must convey the music found within his words. His work has to sing on stage. Spanish has a regular meter and many Spanish words end in a vowel, unlike English, so a translator has to preserve the elegance of the original Spanish while also creating rhythms in English that rhyme.”

To underscore the musicality found in Lorca’s work, Lopez’s version will feature live music, which will be performed onstage by a Spanish guitarist. The production will be directed by Mexican-born Melia Bensussen, no stranger to Lorca’s work: she wrote an introduction to Lorca’s plays, translated by Langston Hughes and W.S. Merwin.

“Another challenge in translating and adapting the play is to make sure it is fresh and contemporary,” Lopez continued. “And I want to move audiences away from what I call the image of black laced-up booted women that many theatergoers – who may have attended earlier productions of Lorca’s plays – have had fixed in their minds.”

Yerma tells of a woman’s longing to become pregnant but is unable to. Her need to give birth become an obsession, encouraged by that fact that she lives in a farming community populated by large families.

“The play is about fertility,” she said. “It is set in a rural community. The land is so productive — her husband has crops that are bursting in the fields — so I thought a lot about where my production could be set, and northern California seemed like a kissing cousin, geographically, to Lorca’s original locale of southern Spain.”

Adapting Lorca for the stage required Lopez to transform the dramatist’s language and landscape. Staged “in a more intimate space. Lorca’s work is lengthy,” she explained. “I’ve shortened and simplified his rhythm and rhyme, as if Yerma is making it up on the spot. Where Lorca is complex and imagistic, my work feels more like a conversation you would have with a three-year old. But it is also full of foreboding — this woman is desperate — and I’m looking for ways to telegraph to the audience that this longing that she feels, it isn’t exactly normal. It isn’t exactly healthy. It has almost a Grimm’s fairy tale quality, which I am really happy with.”

[Editor’s Note on Yerma: Lorca’s play about a woman obsessed with having a child has plenty of contemporary appeal — and often inspires treatments with auteurist flair. Interesting to speculate why that is. Director Simon Stone’s rough, raw, and exhilaratingly free adaptation — staged at the Young Vic in 2017 — is set in contemporary London. The production won a Olivier Award for Best Revival, and was brought to New York. (Would a company in Boston have the nerve to present this sexually upfront version?) An American update, entitled Yerma in the Desert, received its world premiere in late 2017 at the University of Southern California. This adaptation “takes Lorca’s tale of a childless young woman searching for love at any cost and places it in the halls of an elite university in a Trumpian dystopia.” — Bill Marx]

Rosita (Malana Wilson) in the Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival’s production of “Doña Rosita the Spinster,” set to be staged in Provincetown, MA in late September. Photo: Ride Hamilton.

David Kaplan, director/impresario/curator of the Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival, now in its 13th season, began experimenting with Lorca’s last lyrical play, Doña Rosita the Spinster, in New York workshops with his acting students in 1982. Over the years, he has workshopped the play with pupils in Los Angeles and in Mexico. His latest presentation of the play brings a troupe of students from Texas Tech in Lubbock, Texas, to Provincetown for a production that will run Sept. 27-30 at Wharf House in Provincetown, MA.

“The theme of this year’s Festival is ‘wishful thinking,’” Kaplan said in an interview. “And Lorca’s play is about the passage of time and the necessity of hope, the cruelty of hope, that we all cling to as a way of coping with life.”

Like Lopez, Kaplan intends to incorporate music throughout the play which tells the story of the unmarried Rosita, now aged 40, who maintains a child-like vision because, at age 15, she was promised to wed her cousin but was left waiting — for 25 long years.

“Lorca wrote that the play be divided between gardens and include songs and dances,” Kaplan explained, “and we will remain faithful to that vision. We will include a classical Spanish guitarist and a harpist throughout the production.”

Working with a cast of 10, Kaplan said the production pays homage to Lorca’s first theatrical impulses.

“When Lorca was a boy, he put on shows using puppets and dolls, performing them for his cousins and his neighbors at his family’s home in Spain,” Kaplan insists. “Our production will include these elements, too, to give the audience a full experience of Lorca’s imagination and theatrical vision.”

Why, in a festival devoted to the works of Tennessee Williams, did Kaplan choose to include works by Lorca?

“James Laughlin, the founder and publisher of New Directions, who published both Lorca and Williams, wrote, when he first met Williams, ‘He reminds me of García Lorca,” said Kaplan. “Williams, like Lorca, wrote with a poetic voice and incorporated music — in his language and with instruments — onstage. And, like Lorca, Williams explored what lies deep within the souls of his very human characters.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel, and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Tagged: David Kaplan, Doña Rosita the Spinster, Federico Garcia Lorca, Melinda-Lopez, Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival