Jazz CD Review: Miguel Zenón — An Extraordinary Scholar/Composer

Miguel Zenón’s extraordinary writing for strings and saxophone makes use of ever-changing textures generated out of jazz, Puerto Rican folk, and classical music.

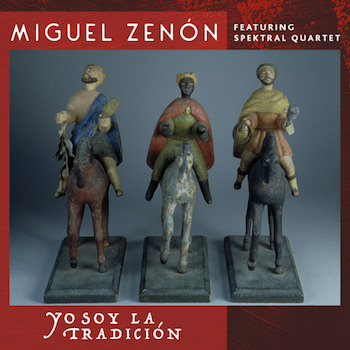

Miguel Zenón and the Spektral Quartet: Yo Soy La Tradición (Miel Music)

By Michael Ullman

This recording of saxophonist Miguel Zenón features his writing for alto and string quartet. The result is not only a sophisticated delight but, for this listener, a genuine education. Some readers will remember Zenón’s previous disc, Identities are Changeable, a project that began when the saxophonist, who was born and raised in Puerto Rico but living in New York, became curious about the tenacity with which second and third generation Puerto Ricans living in New York clung to their musical and cultural traditions. He started to interview them, and they inspired him to write music that reflected their resilient spirit and embattled experiences. In this sense, Zenón is a kind of scholar/composer, an inquisitive soul whose discoveries — about life, love, and history — are transformed into music. In the case of Yo Soy La Tradición, Zenón is drawing on venerable Puerto Rican musical traditions, some two hundred years old. In his album notes, he informs us, for instance, that his tune “Rosario” is related to music traditionally performed during funerals. In his piece, “each segment of the Rosary is presented in its usual order, but musicalized.”

Zenón, of course, “musicalizes” them in his own way, his extraordinary writing for strings and saxophone generating ever-changing textures inspired by jazz, Puerto Rican folk, and classical music. Zenón has said that he studied string quartet writing extensively before composing these pieces. It shows: given his use of sometimes quicksilver lines, the witty as well as sensuous exchanges among instruments, I imagine he listened to Haydn as well as to Bartok. In most jazz “strings” albums, the arranger uses violins as a lachrymose bed for the soloist to lie down on. Not here. “Rosario” begins with a kind of twittering sound from the high strings as the cello states a short, folksy melody. The saxophone intrudes almost immediately, providing a cadenza-like flurry, then pulls back to allow the strings to state the melody one more time. The sax then dominates, playing over pizzicato passages by the strings as well as lushly bowed accompaniments. In a second section the tempo increases as the strings suddenly become agitated. My description of the piece makes Zenón’s writing sound busy, but space as well as a kind of logic shapes its lyricism.

“Cadenas” is a light-hearted, dance-like number whose bouncy melody is initially suggested by the first violin. Complicated lines played in unison by the composer and strings follow, then a short saxophone solo comes along before the dance melody recurs, this time with more dissonant accompaniment.

“Promesa” is a musing number introduced by the cello. At one point, the quartet divides; the upper strings play a staccato chord repeatedly while the cello supplies a long, slow melody. Eventually the saxophonist enters and (I am guessing here) improvises over a quickly evolving background. The ‘promise’ at the center of the song is one that the Catholic makes to a saint in return for a special favor. This scenario brings out the composer’s most virtuosic playing on the session. Yo Soy La Tradición certainly lives up to its promise: this album is filled with fascinating music, marvelously realized and unlike anything else I know.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.)