Visual Arts Commentary: “Keepers of the Flame” — The Revenge of the Middlebrow

This special exhibition is arguably the most insightful and compelling organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum.

Keepers of the Flame: Parrish, Wyeth, Rockwell and the Narrative Tradition at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA, through October 28.

By Charles Giuliano

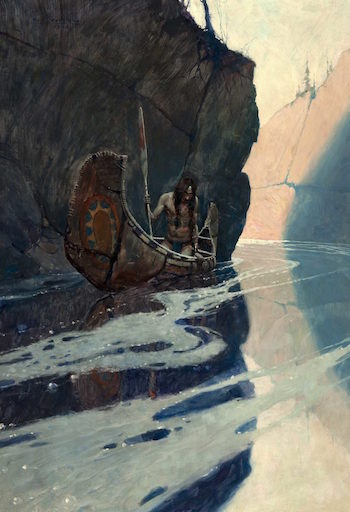

N. C. Wyeth, “In the Crystal Depths,” 1906. Illustration for “The Indian in His Solitude.” Photo: courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

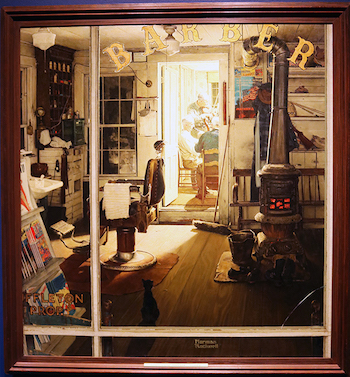

Arguably a masterpiece by the illustrator Norman Rockwell, “Shuffleton’s Barbershop” (1950), a work he donated to the Berkshire Museum, was sold privately by the New York auction house Sotheby’s to The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art. While that museum is under construction, the iconic painting is on loan to the Norman Rockwell Museum for 18 months.

Through October 28 the picture is the centerpiece of a stunning, richly documented, special exhibition Keepers of the Flame: Parrish, Wyeth, Rockwell and the Narrative Tradition. Curated by an illustrator, Dennis Nolan, the author of a definitive catalogue, it took five years for the museum to organize and secure the necessary top notch loans. This special exhibition, arguably the most insightful and compelling organized by the museum, includes more than 60 original works by those masters and nearly two dozen other American and European painters.

A reprieve of “Shuffleton’s Barbershop” in the Berkshires, the subject of global media attention, is an incentive for visitors. That iconic painting is flanked by masterpieces by the three illustrators as well as American and European masters they studied with and were influenced by.

Maxfield Parrish (July 25, 1870 – March 30, 1966), Newell Convers Wyeth (October 22, 1882 – October 19, 1945), known as N. C. Wyeth, and Norman Perceval Rockwell (February 3, 1894 – November 8, 1978) were the dominant artists of the golden age of American illustration.

If one picture speaks a thousand words, then the language of these paintings, books, and posters have shaped the American psyche. Wyeth created over 3,000 paintings and illustrated 112 books. Parrish produced almost 900 murals, calendars, greeting cards, and magazine covers. Rockwell is best known for some 300 covers of Saturday Evening Post. His “Four Freedoms” a series of 1943 oil paintings, reproduced as posters, were a part of the war effort. An exhibition and accompanying sales of war bonds raised over $132 million.

The Norman Rockwell Museum includes over 800 of his works. There are 175 painting as well as sketches and studies. In addition the museum has acquired 15,000 other works through gifts.

In the Cold War era of the 1950s there was a paradigm shift in publishing. The illustrations of Saturday Evening Post gave way to the photo journalism of Life Magazine, Time, and Newsweek. The taste for avant-garde grew; the sentimental propaganda, genre, and Americana of illustrators were dismissed as kitsch by influential critics, most scathingly by Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg. Greenberg ridiculed Rockwell while he celebrated abstract expressionism. Rockwell, however, remained politically relevant through illustrations focused on Civil Rights.

When my generation studied art these illustrators were viewed as anathema. The success of the Norman Rockwell Museum, which has 2,000 daily visitors in high season, speaks to a change in taste. His painting “Saying Grace” sold for $46 million to George Lucas in 2013.

Norman Rockwell, “Shuffelton’s Barber Shop,” 1950. Photo: courtesy of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

Given the global interest in Rockwell, because of the Berkshire Museum controversy, I asked Laurie Norton Moffat, director of the Rockwell Museum, how that has impacted critical evaluation of the artist?

“I think we’re seeing a resurgence of affection that existed during his lifetime.” She said. “The fine arts community had not considered Rockwell and the illustrators in the pantheon of American art. You have to take into account the millions of average citizens who always considered him to be their favorite artist. What we have now is all of the people who have loved his work as well as a broadening perspective toward narrative painting and realism. It is work that the art world is looking at and weaving together. From the perspective of the past fifty years we are seeing a renewed respect for narrative painting, realism, story telling, and subjective art work.”

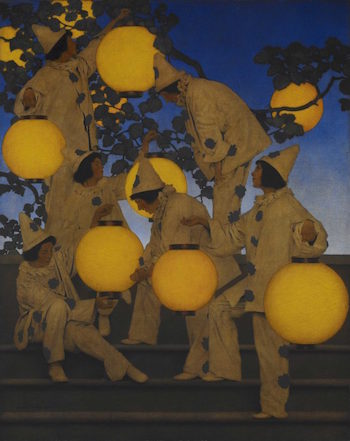

The museum’s stunning exhibition allows me to recall the visuals I grew up with. As a kid, I devoured books like Treasure Island, which were so imaginatively illustrated by Wyeth. The waiting room of my doctor parents offered issues of such magazines as Look, Life, and Saturday Evening Post. Every American home seemed to have framed color lithographs by Parrish.

More than just populist eye candy, however, this exhibition has a didactic mission. The 216 page, profusely illustrated catalog, with essays by Nolan and Alice A. Carter is essential to that heuristic mandate. The volume delineates how generations went through academic training that reached back to the Italian Renaissance. Curator Nolan explores a number of family trees as he delineates the DNA of academic art, mapping out the American masters who studied in European studios.

The Philadelphia realist, Thomas Eakins, is represented by, “William Rush Carving his Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River,” 1908. He studied at École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, under the Orientalist, Jean-Léon Gérôme. Eakins taught Thomas Anshutz, who trained Howard Pyle, who instructed N. C. Wyeth. The patriarch Wyeth spawned a family of artists and illustrators.

Maxfield Parrish, “The Lantern Bearers,” 1908. Photo: Dwight Primiano.

The exhibition carefully tracks the passing of the realist torch, in the process enriching our understanding of the rigorous training required of illustrators. They mastered drawing the figure as well as creating from their imaginations. Intense research was required in order to complete their illustrations: costumes were created; sets were constructed; studies and sketches were referenced.

In 1839, Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre created the first photographs. Various camera devices had been used by artists, including Vermeer. The development of photography made an enormous impact on L’art pompier, represented here via absurdly sentimental paintings by Gérôme, William Adolphe Bouguereau and Marc Charles Gleyer.

High speed, offset color printing encouraged what philosopher, cultural critic, and essayist Walter Benjamin described in 1935 as “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Post war Abstract Expressionism was a reaction to illustration, Social Realism, and Regionalism. Pop followed, serving up parodies of mechanical reproduction. Art historians have bounced about, via Newtonian action and reaction.

The hegemony of Greebergan formalism evolved into pluralism and post modernism. The shattering defraction of advanced critical thinking has had the curious result of revisionism and post millenial populism. The scholarly approach of this exhibition potently demonstrates how this process plays out. Standing before the often cloying works in this exhibition is often dizzying. It’s a tug of war between heart and mind. One turns back to Dwight Macdonald’s influential 1960 essay “Masscult and Midcult,” with its categories of “Highbrow, Middlebrow, and Lowbrow,” and wonders if those aesthetic lines can ever be re-drawn.

Charles Giuliano is publisher/editor of the on line Berkshire Fine Arts. This summer he will publish his fifth book of verse. In July, a retrospective of portrait and performance photography, Heads and Tales, opens at Gallery 51 of Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts in North Adams, Massachusetts.

Tagged: Keepers of the Flame, Maxfield Parrish, Norman Rockwell

excllent review. I will go!