Rethinking the Repertoire #25: Esa-Pekka Salonen’s “Foreign Bodies”

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the twenty-fifth (and final) in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

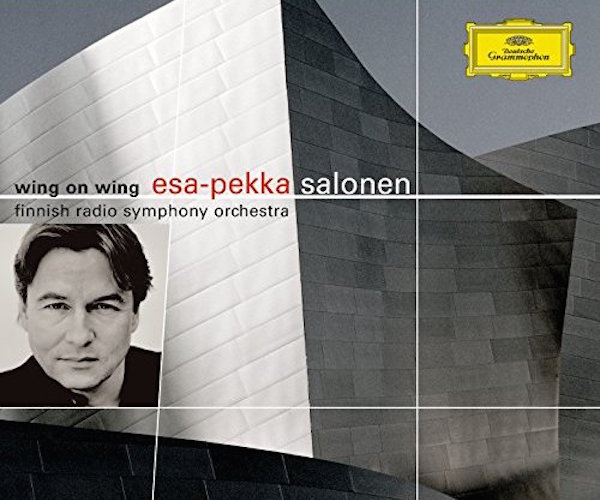

Composer Esa-Pekka Salonen.

The number of world-class composers who were also world-class conductors has always been pretty small. Mendelssohn and Berlioz top the early-19th century list, Mahler and Richard Strauss the fin de siècle (and, for Strauss, early 20th-century) one, and Leonard Bernstein’s pretty much the sole occupant of the honor between World War 2 and his death in 1990. These days, there’s just one, too: Esa-Pekka Salonen, the former music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and current principal conductor of London’s Philharmonia Orchestra.

Born in Helsinki in 1958, Salonen began his career studying horn and composition, in addition to conducting. With Magnus Lindberg and Kaija Saariaho, he founded the Toimii Ensemble, and, a few years later with Jukka-Pekka Saraste, the Avanti! Chamber Orchestra.

While Salonen’s on record stating that he mainly became a conductor in order to lead performances of his music, his catalogue from before the mid-1990s is a pretty thin one. There’s an alto saxophone concerto, Floof (a song cycle for soprano and orchestra), and a ten-minute-long orchestral piece called Giro. That’s it.

Part of the reason for this is that his conducting career took off with an alacrity even Salonen might not have anticipated: a last-minute substitution for Michael Tilson Thomas conducting Mahler’s Symphony no. 3 with the Philharmonia in 1983 led to an appointment there two years later as principal guest conductor. By then, Salonen was also principal conductor of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and had made his debut with the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

And the L.A. Phil is the orchestra with which Salonen will forever be associated. Eight years elapsed between his debut with them and his assuming the orchestra’s directorship in 1992 (not to mention some drama between Salonen, the Philharmonic’s then-executive VP Ernest Fleischman, and the-music director Andre Previn). But, once established in the role, Salonen and the Philharmonic almost single-handedly reinvented the model of the late-20th-/early-21st-century orchestra.

Together, they gave pride of place to new and contemporary music, in seventeen years commissioning over fifty new works and premiering more than 100. They found ways, thanks in large part to the successful relationship Salonen cultivated both with Fleischmann and his successor, Deborah Borda, to make the orchestra central to Los Angeles’s cultural life (the Frank Gehry-designed Walt Disney Concert Hall, opened in 2003, being an enduring, visual manifestation of this). Most importantly, Salonen and the Philharmonic had an electrifying chemistry together, especially when playing late-Romantic and 20th-century fare.

And, remarkably (given his workload), that magnetism led to a revival of Salonen’s career as a composer. Indeed, when he stepped down from the Philharmonic’s directorship in 2009, Salonen was more than a decade into his renaissance as a composer and his last concert in L.A. featured the first performances of his (eventually Grawemeyer Award-winning) Violin Concerto.

This resurgence in writing had begun, appropriately enough, with a piece for the Philharmonic, LA Variations, that Salonen composed in 1996. Well received, the Variations were followed by a series of further works: Five Images After Sappho (1999), Mania (2000), Insomnia (2002), Wing on Wing (2004), and Helix (2005). A series of concertos came next, beginning with 2007’s Piano Concerto (written for Yefim Bronfman), and followed by the Violin Concerto (for Leila Josefowicz), and, more recently, a Cello Concerto (for Yo-Yo Ma). Further orchestral scores (like Nyx and Karawane) plus some chamber music (Homunculus) fill out his catalogue.

What does it all sound like? Well, aptly, for a composer who hails from Finland but found his spiritual home in Southern California, Salonen’s is a singular musical voice. Sure enough, there are echoes of his European training, from the old canon through to late-20th-century Modernism. And, especially in his scoring, there’s an opulence and invention that only decades of experience as a conductor can bring. But there’s nothing dogmatic or unduly complicated about Salonen’s mature works. Quite the opposite: they tend towards clarity (of line or gesture) and directness of expressive purpose.

There are certain trademarks to be found in his music, too. Oftentimes there’s a contrast between vigorous, rhythmic writing and big, dense chorale-like textures. His melodies sometimes evoke what he calls a “synthetic folk music,” something Bartók might have concocted if he’d had access to Ableton Live. It embraces, thematically and philosophically, technology and science. Along the way, it’s happily eclectic, drawing on everything from post-grunge mantra rhythms to purely abstract images and metaphysical concepts.

One of my favorite Salonen scores is a piece that demonstrates many of these characteristics. It’s his 2001 orchestral piece Foreign Bodies, a three-movement work that, in Salonen’s words, reveals “the fact that I am less concerned about the purely cerebral aspects of music and more interested in the physical reality of the music.” In other words, it’s a piece that announces Salonen’s rediscovery of the fundamental elements of music in his writing.

That’s not to say that Foreign Bodies is a simple piece: in terms of rhythm, texture, technical demands, and instrumentation it’s anything but. Still, it’s engaging on first hearing and has plenty of secrets to explore on subsequent listenings.

Its first movement, “Body Language,” is partly based on Salonen’s solo-piano piece Dichotomie, taking the earlier score’s opening bars as its point of departure. A study of machine-like energy – Salonen likened the movement’s gestures not to a “watchmaker’s precision instruments but huge and extremely massive things that consume enormous amounts of energy” – it subjects its initial, rocketing fanfare motive to a series of striking, often subtle transformations as it proceeds.

That said, not everything’s driving and loud here: a lush, dissonant chorale turns up like a rogue wave about a third of the way in and much of the movement’s middle part is devoted to a series of playful episodes. The movement ends peacefully, too, with a woodwind and brass melody unwinding beneath softly pulsing strings.

Foreign Bodies’ second part, “Language,” draws on a choral song Salonen wrote to a text by Ann Jäderlund called “Deep Within the Chamber.” Its textures, often delicate and ethereal, are punctuated by two climaxes: the first introduced by a thick viola chorale, the second by a syncopated melody passed around the orchestra.

In the finale, “Dance,” the music, which has hinted at cutting loose at times in the earlier movements, finally does so. Especially over “Dance’s” first half, Salonen’s scoring shines like polished glass: low strings are de-tuned to produce what the composer describes as “unusual” natural harmonics and, as they glow, little, palpitating figures played by winds, brass, and percussion jump out in sharp relief. Eventually, the first movement’s main motive imposes itself on the proceedings and Foreign Bodies ends in a mechanistic climax – but a joyful one at that: the last sound we hear is a thunderous C major cadence.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.