Music Interview: The Oak Ridge Boys Get Hip With Gospel

The mainstream country trappings of the Oak Ridge Boys have obscured their crowning achievement: they helped bring the white gospel quartet tradition to the pop charts.

By Noah Schaffer

At one point the Oak Ridge Boys were such a constant presence on country radio that the Austin Lounge Lizards issued a musical call to Put the Oak Ridge Boys in the Slammer.

At one point the Oak Ridge Boys were such a constant presence on country radio that the Austin Lounge Lizards issued a musical call to Put the Oak Ridge Boys in the Slammer.

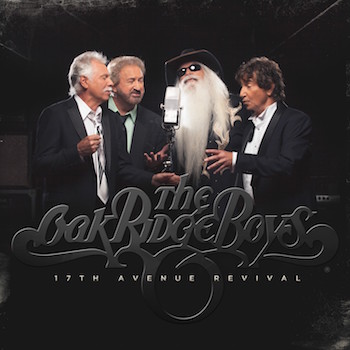

But times have changed, and when the group sat down with in-demand Americana producer Dave Cobb to plan their new album they immediately agreed that there wasn’t any point in making an airplay-friendly record. The result was 17th Avenue Revival, an LP that celebrates how both black and white gospel inspired early rock ‘n roll. Highlights includes a rockabilly take on Rev. Charlie Jackson’s gospel-blues God’s Got It and Brandy Clark’s Pray to Jesus, which is turned into a boogie-woogie steam train.

While unlikely to rack up sales figures that would rival their chart smashes like “Elvira” or “Bobbie Sue,” the album gave the Oaks something that has often eluded them: critical respect. Proudly ideologically right wing off-stage and prone to the saccharine (“Thank God For Kids”) the Oaks’ mainstream country trappings have tended to obscure their crowning achievement: Along with the Statler Brothers, they brought the white gospel quartet tradition to the pop charts, in the same way Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin put the sound of black gospel into the Top 40.

Eternal road warriors, the Oak Ridge Boys’ tour schedule takes them to places most classic country veterans skip, such as the North Shore, where they’ll play the Cabot Theater in Beverly on May 20. Bass singer Richard Sterban, whose career has also included a stint backing Elvis Presley as a member of the Stamps Quartet, recently spoke to the Arts Fuse from his Nashville home.

Arts Fuse: The Oak Ridge Boys began in the ’40s as a Southern gospel group. But on the new album you perform a black gospel song, “God’s Got It.” Is this the first time you’ve done this kind of material?

Richard Sterban: We had done a little bit in the past, but I have to give our producer Dave Cobb a lot of credit for both that song and the whole project. Two and a half years ago we were inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame — certainly the greatest honor of our careers — and we got together and decided we wanted to do something unique and special to commemorate that occasion. We had worked with Dave a few years ago on an album called The Boys Are Back where he took us down some roads we hadn’t been done before, such as a cover of the White Stripes’ “Seven Nation Army.”

But since then he had became really hot working with Chris Stapleton, Jason Isbell, Zach Brown Band, and so we had to get in line. It took a year for him to have time to deal with us. We met on Music Row and he laid out a vision that was a bit different from what we had been expecting. He said think about Elvis, Jerry Lee Lewis, Ray Charles, the blues guys — what was it that made them so special and made us love them? What did they have in common? The answer was that they all started singing in church. Cobb’s mom was a preacher so he knew about gospel. So he wanted to go back and dig into black gospel — he had to get some of the lyrics from the Smithsonian! — and have us perform some of the hymns we grew up on, as well as some songs by contemporary country writers.

“God’s Got It” is one of the songs we recorded with just the four of us standing around a microphone. It reminded me of the album Rick Rubin made with Johnny Cash, where it was just him and a guitar.

AF: At one point the Oaks were a staple of country radio, but I read that Cobb told you at the outset of this project that mainstream radio airplay would likely be off the table. Was that a difficult thing to hear?

Sterban: That’s another thing he said: “I don’t want to worry about country radio — let’s forget it, they’re not playing you anyhow so let’s not worry about that.” And yes, hot country radio will not be playing anything off this project, although classic country and gospel stations are. Country has changed, it really has, and when I look at the award shows and listen to the radio I can understand why we don’t fit in.

But I don’t have a problem with it. Nothing stays the same, we had our run for about 15 years where just about everything we released went to the top of the charts, so we can’t complain. I think all these young kids that have come have really raised the bar several levels, and the business is better than it’s ever been as a result of what these young kids are doing. Groups like Florida-George Line are bringing in a lot of new country music fans and I think that bodes well for the future. We’re just happy to have our little niche.

The Oak Ridge Boys. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

AF: People say that a lot of today’s country isn’t country enough — but didn’t they say that about the Oaks at one point?

Sterban: It’s really funny — years ago when we first came on the scene and released hit records a lot of people criticized us for not being country enough. Now we are considered classic country! We’ve done things with Blake Shelton and Miranda Lambert…where we’ll sing “Elvira,” and the kids who listen to them seem aware of who the Oak Ridge Boys are.

AF: You were the first New Jerseyite inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. How did you get into Southern gospel being from the East Coast?

Sterban: Oh, I was raised in church — like all the Oak Ridge Boys I pretty much had to go every time they opened the church doors! In college I helped organize my own group with some guys from Bristol, Pennsylvania called the Keystone Quartet. [Oak Ridge Boy] Joe Bonsall was a member too. And when I was with the Keystones I got a call from JD Sumner in Nashville, who was in the Guiness Book of World Records as the lowest bass singer. He wanted to hire a young bass singer to take his place.

I took the job and we were singing strictly gospel, but six months into it JD got a call from Elvis. He had been using a different gospel group, the Imperials, but they had a conflict and we became Elvis’ backup group. So of the two years I spent with JD, 18 months were with Elvis. Just yesterday I got a nice check for a record I sang on [nearly] 50 years ago, Burning Love. When I was with Elvis I got a call from William Lee Golden telling me that the Oak Ridge Boys’ bass singer was leaving. I was really a big fan of the group and thought they had a great deal of potential. A lot of people questioned my decision to leave Elvis, but history has proven that it was a really good decision! And for the first few years after I joined Oak Ridge Boys they strictly did gospel. It wasn’t until 1977 that we had our first country hit with “Ya’ll Come Back Saloon” and then “Elvira” made us a household name in 1981.

AF: At that point Elvis was working a lot in Las Vegas. Was it strange to be singing gospel in such a secular environment?

Sterban: Maybe a little bit. But you know, Elvis may have been the king of rock ‘n roll but his favorite music was gospel music. He especially loved black gospel. Some of my fondest memories of working with Elvis is that whenever we were on tour [backstage] he’d try to find a piano and go back to the Stamps Quartet and we’d start singing gospel quartet songs with him. And Elvis made sure he had a gospel segment on just about every show. Being on the stage in Las Vegas singing vocal backup when he sang “How Great Thou Art” — he tore the crowd apart — you felt you could look up in the sky and see Jesus in the clouds.

After I joined the Oak Ridge Boys we ended up going back to Las Vegas with Johnny Cash. If Elvis was the most special person I ever knew, Johnny was a close second. When he walked into a room you’d feel his presence. When we were working with him we were struggling because we were in this grey area between gospel and country. Cash could tell we were struggling. He always paid us more money than we were worth. And he’d tell us, “I can tell your heads are hanging, but there’s something very special about the four of you. If you give up no one else will ever know how special you are. I want you to find a way to stay together.” We walked out of there with our heads up high. If not for Johnny Cash, there wouldn’t be an Oak Ridge Boys today.

Over the past 15 years Noah Schaffer has written about otherwise unheralded musicians from the worlds of gospel, jazz, blues, Latin, African, reggae, Middle Eastern music, klezmer, polka and far beyond. He has won over ten awards from the New England Newspaper and Press Association.