Classical CD Reviews: Michael Brown’s Piano Works, Ferdinand Ries Piano Concertos, and Andris Nelsons’ Bruckner Symphony no. 4

Variations and fugues are the overriding themes of pianist/composer Michael Brown’s captivating new album. If you’re an Andris Nelsons fan, this Deutsche Grammophon album won’t disappoint, and a disc that features three pieces by composer Ferdinand Ries, who was friendly with Beethoven, is worth hearing.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

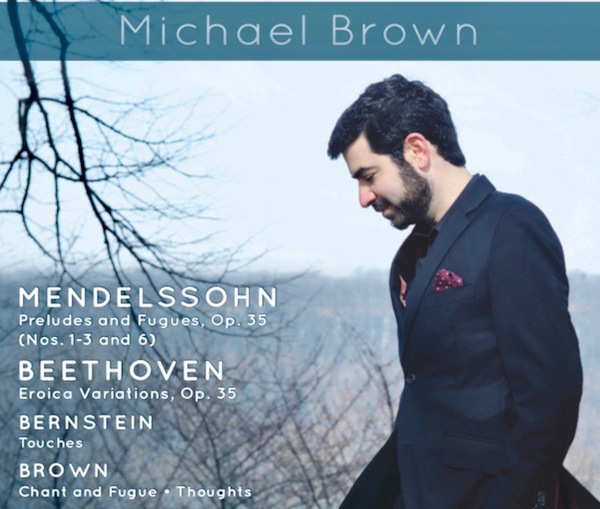

Variations and fugues are the overriding themes of pianist/composer Michael Brown’s captivating new album (on First Hand Records) that pairs his own music with pieces by Leonard Bernstein, Felix Mendelssohn, and Beethoven.

Brown is represented by three short pieces that total just under seven minutes of music. Two movements from his Piano Suite – “Chant” and “Fugue” – offer, respectively, plaintive, floating lyricism and spiky, energetic gestures. The stand-alone Thoughts is, essentially, a short song for solo keyboard.

Together, they reveal a composer who’s perfectly at home writing affecting miniatures for the piano, ones that brim with personality and sometimes head off in surprising directions. The “Fugue,” for instance, is a spirited discussion on an angular motive that builds in intensity only to peter out in Ives-ian fashion. And the closing bars of Thoughts fade ominously.

The three Brown scores also offer a nice contrast to Bernstein’s Touches, a set of variations on a bluesy theme that has been largely neglected since it was written in 1981 but seems to be undergoing a renaissance of late; Brown’s recording is at least the third to come out in the last twelve months.

And it’s an excellent one, gleaming and full of vim. The pianist easily navigates the music’s considerable demands, paying special heed to the score’s copious dynamic and articulation instructions. Paradoxically, the strength of Brown’s interpretation tends to emphasize some of Touches’ structural shortcomings (like the austere brevity of some of its middle variations). But he imbues its biggest moments (the searching fifth variation, epic Coda) with heat.

Framing the album’s American contributions come a gripping account of four of Mendelssohn’s six Preludes and Fugues, op. 35, and Beethoven’s Eroica Variations (his op. 35).

Brown dispatches the Mendelssohn’s sometimes very knotty chromaticism with exceptional clarity and – always – a strong sense of the musical line. Thus, the fugues are anything but pedantic, pseudo-Bachian exercises: Brown’s account of the opening E-minor one, for instance, is packed with energy and drama, the chorale at its end not only perfectly balanced between the hands but, emotionally, truly cathartic. The concluding sixth fugue (in B-flat major) is a marvel of propulsion and snappy rhythmic activity.

Brown also mines much beauty and drama out of the preludes. The E-minor Prelude is plenty turbulent (and exquisitely voiced). The D-major floats dreamily, while the B-minor flits by nimbly. Best is the luminous, rather Lisztian B-flat-major Prelude, whose thick, chordal accompaniments never drag down its lyrical main tune.

The Eroica Variations sound appropriately heroic here and Brown revels in their quirks – the cadenza in the second variation and seventh-variation canon with thudding bass interjections speak with real wit – as well as their anticipations of things to come (like the eighth variation’s anticipations of the Waldstein Sonata’s finale’s textures).

This is an altogether smart and enjoyable release.

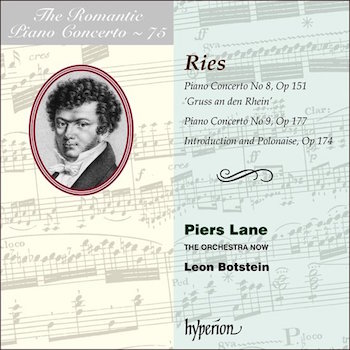

If you only know the name Ferdinand Ries due to his friendship with Beethoven, take heart: you’re not alone. He was a prolific composer in his own right, though, with a series of symphonies, operas, and a boatload of concertos (including nine for the piano) to his name. Two of the latter, nos. 8 (in A-flat major) and 9 (in G minor) are paired with his Introduction & Polonaise on the seventy-fifth installment in Hyperion’s “Romantic Piano Concerto” series.

They are, all three, wonderfully tuneful pieces filled with often-dazzling touches of virtuosic derring-do. If the music, generally, owes a debt to Beethoven, well, suffice it to say that 1) it never overstays its welcome, 2) it offers plenty of quirks of its own, and 3) what Beethoven appropriated from contemporaries like Ries and vice versa is, at this point, rather difficult to determine. Regardless, this are pieces worth hearing.

That’s especially true when they’re played with the dexterous command and poetic fluency that pianist Piers Lane brings to them here. In the A-flat-major Concerto, he dispatches the florid runs of the outer movements vigorously and with color to spare; the lovely central movement sings like a long-lost Chopin nocturne.

A similar approach marks Lane’s account of the G-minor Concerto which, in the minor-key episodes of the outer movements (both of which end in the major mode, for what that’s worth) boil turbulently. The central Larghetto is, again, free and songful. And the Introduction & Polonaise is a brilliantly vital.

Leon Botstein and The Orchestra Now provide charismatic accompaniments, full of rhythmic bite and spirit. Indeed, it would be hard to ask for more finely-etched or sensitively played performances of such neglected fare as this. None of these three scores may be earth-shaking, but they’re fine works that provide fresh perspective on an era (and genres) that have been dominated by too few composers and pieces.

Well, this is an improvement. Last year’s first installment of Andris Nelsons’ complete Bruckner symphony cycle with the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig (of that composer’s Symphony no. 3) was a bit of a misfire: sumptuously played, to be sure, but leaden, portentous, and interpretively dull.

This second, which features the so-called Romantic Symphony (no. 4), tends to flow more naturally. Nelsons’ reading isn’t quite so heavy-footed and he generally doesn’t try to make more of the music’s imposing silences than he should. The Gewandhausorchester, again, sounds as magnificent as ever, playing with burnished tone and drawing out all sorts of sweet little nuances in the music (the first movement’s second theme is given a particularly graceful rendering).

Where Nelsons’ interpretation raises a few eyebrows is in the second movement, in which his tempo is extremely slow (no Andante quasi Allegretto this) and his tendency to imbue the music with more weight and sobriety than it needs sometimes takes over. The finale, too, offers some slowish mannerisms when it comes to dynamic extremes, shaping the ends of the movement’s various sections, and tempo contrasts. And, in its blaze to the end, Nelsons’ reading robs the music of some of its mystery.

Filling things out is an altogether wonderful performance of the Act 1 Prelude to Wagner’s Lohengrin: well-paced, unfussy, and gorgeously balanced.

In the end, then, if you’re a Nelsons fan, this Deutsche Grammophon album won’t disappoint. If you’re not on his bandwagon (yet), there’s quite a bit that goes right, though Nelsons’ remains (appropriately) a young man’s approach to Bruckner. Still, his is well-played and structurally coherent. On top of that, the Wagner selection’s about as good as it gets.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.