Jazz Interview: Composer/Pianist Anthony Coleman — On Being “Avant-Garde”

As part of its 150th anniversary celebration, NEC commissioned Anthony Coleman to compose a large-scale work he has named Streams.

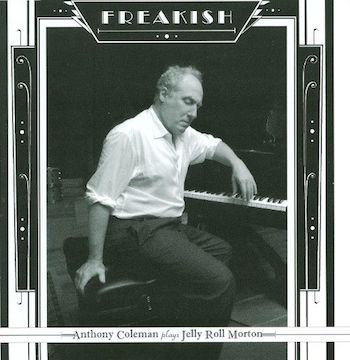

Composer Anthony Coleman. Photo: Andrew Hurlbut.

By Steve Provizer

Anthony Coleman is a prolific composer and pianist who has recorded 15 CDs under his own name, and has played on more than 150. His compositions have been commissioned and performed throughout the world. In the 1980’s, he was an important participant in what became known as the Downtown Scene, along with Glenn Branca, Elliott Sharp, Marc Ribot, and John Zorn, which broke down musical barriers, stretched genre definitions, and introduced Radical Jewish Culture as a compositional and improvisatory element.

Coleman earned an undergraduate degree from New England Conservatory (NEC), a master’s degree in composition from the Yale University School of Music and returned to teach at NEC in 2006. As part of its 150th anniversary celebration, NEC commissioned Coleman to compose a large-scale work he has named Streams. The piece will receive its world premiere on May 2 in Boston’s Jordan Hall. As you will see from his responses to my questions, Coleman has thought deeply about what he does, and can talk about it in an incisive and down-to-earth way

Arts Fuse: You started piano studies with the singular Jaki Byard when you were quite young. Can you tell us how that came about and a little about that experience? Also, we know that Morton, Ellington, Monk and Taylor are touchstones for you, but apart from Jaki, did you have any other piano mentors?

Anthony Coleman: Well, I went to a private school that was very permissive. One of my teachers had many faults, but his love for black culture and jazz was inspiring. I was 12 years old and he did many things: he took us to see Rahsaan Roland Kirk at the Village Vanguard and he brought Jaki Byard in as a guest. I was fooling around with a lot of musical ideas, but I hadn’t found one that had really landed. I’d spent time trying-pretty unsuccessfully-to learn to play Elizabeth Cotton style finger-picking guitar, but I had done a class project on Scott Joplin and that inspired me because, especially in the book They All Played Ragtime, Rudi Blesh and Harriet Janis talked a lot about Joplin as somebody who took things from folk music and transformed them as a composer. That really intrigued me.

But I didn’t think I wanted to stay with old forms of music. I wasn’t a retro kind of person. Then I heard Jaki and he had that way of encompassing the history. I went up to him and very timidly asked him if he taught and he said he did, s I started studying with him and I stayed with him all through high school, which was an incredibly inspiring experience. Jaki also suggested that I go to New England Conservatory but once I got to NEC I never actually studied with him again because I became a jazz composition major and after one year I switched to the composition department.

I never really studied piano with anybody else. I had a couple of lessons with Roland Hanna and a couple of lessons with Harold Mabern but I wouldn’t say in terms of mentors that I ever really had anybody else. More recently I went back and studied for a year with Sophia Rosoff — she really helped me with some technical aspects in the Jelly Roll stuff. [See Coleman’s recording: Freakish: Anthony Coleman Plays Jelly Roll Morton]

AF: As a pianist and as a composer, you are identified as being “avant-garde.” First, as an early 20th century coinage, do you think the expression still has meaning? Can you define it now and do you think that label is properly associated with you?

Coleman: There’ll always be people who are trying to push the envelope, after first finding out what the current envelope is, and as long as there are people who really do that there will still be the concept of avant garde. I’m not sure that I have seen many things lately that I would identify as avant garde particularly, but that doesn’t mean that it’s dead. I mean, there have been other periods where that’s less the ascendant new thing. Like, if you think about the period of neoclassicism you wouldn’t call those people avant garde even though they were the new thing that was happening. So I don’t think we’ve seen the last of it.

One of the things that a lot of people — in this particular case I’m talking about Michael Nyman in his book on experimental music — do is make a huge distinction between avant garde music and experimental music. Various people have made these distinctions having to do with some kind of lineage or whatever. He identifies say Boulez and Stockhausen as belonging to the avant garde and Christian Wolff and John Cage as being part of experimental music and, as a teacher, I find these distinctions very interesting. But, talking about my own work, it would mean squaring various circles in order for me to define it. I’m the product of many different ways of thinking about style and language — some of them are connected to experimental or avant garde traditions and some of them are not. I’m probably not the best person to define myself.

AF: Staying in that area, some of what you do is employ sounds that push the envelope, toying with boundaries, sometimes even moving into the category of noise. This expanded sonic palette has been around for a long time now. Do you think that the ears of listeners have expanded to more easily assimilate these sounds, or not?

Coleman: That really depends; I mean, you could call it a category at this point, so in that case there are people who know that they like it. But I would say my own audience has become smaller. There was a period in the ’80s and ’90s where we thought we were going to break through some kind of niche that bordered the mainstream. That was true for a brief period. It created a lot of interesting energy, not all of which was positive — it really depends.

Let me tell you a story: I went to a Bjork concert in New York in 2001 not long after 9/11. Matmos [an experimental electronic music duo] played an opening set and the very people who listened to her album Vespertine and loved the sound of that kind of musical landscape when Bjork’s voice was in the foreground were literally going nuts listening to the Matmos set; they were fidgeting and complaining. It’s so interesting that a foregrounded singer with a strong personality can make audience members accept that kind of music, but when they actually have to sit down and listen to that music in an instrumental form they freak out – so I have very mixed feelings about audiences based on that experience and other experiences that are similar.

AF: You have used painting to talk about your own music. For example, there’s your love of the grotesque in German Expressionism — George Grosz and Otto Dix and the influence of “primitive art” on Dubuffet. Can you identify how the “grotesque” and/or the “primitive,” in this context, relate to your own music?

Coleman: Well, there’s a lot of fascination with different contexts and different constructions of rawness. I mean, coming out of New England Conservatory and Yale School of Music and coming back to New York in 1979 and being plunged right into the middle of No Wave was a really ear-opening experience for me. I am lucky that I was able to hear that music when it was new and also to recognize the mastery in those people, some of whom are not particularly musically trained but who had an idea of sound and an idea of something that they needed to express. Dubuffet is an important source of inspiration because he tried so many ways to engage with all of that in his own work.

Of course, there’s always the danger of high-culture appropriation of things and fetishization of some idea of “The Primitive,” whether it’s about people who come from other cultures or untrained people or whatever. And this realization has pushed me to be thoughtful about how you have to be aware of bringing in some kind of cultural bias or sense of high/low that you may think that you are exempt from. You look at other people and you know that they’re thinking in that way and you think “I recognize the greatness of (something) and I’m not under the spell of those kind of hierarchies.” But you might be wrong!

The late pianist and poet Cecil Taylor, one of the inspirations for “Streams.” Photo: BMI.

AF: Your composition Streams, premiering at the upcoming concert at NEC, comes with this billing: “Streams draws inspiration from recent events, including the passing of Cecil Taylor [on April 5 at the age of 89] and the Parkland massacre.” First of all, how and why did these things inspire you? Secondly, do you have any thoughts on the relationship between making art and reckoning with current politics/cultural events?

Coleman: Music has a very limited ability to tell particular stories. Music’s stories are basically the stories of its own existence in time and space. You can draw inspiration from anything and with programs or notes you can push the listener to draw the same associations that you’re drawing on, but it’s also possible to just enjoy the fact that music has a very slippery and trickster-like relationship to semantics and language. I don’t confuse the things that inspire me with what it is that I want an audience to take away.

Perhaps it’s more that I would like them to feel the intensity of my engagement with the world, including times when I feel the intensity of my disengagement, my anomie, and so on. In the case of the piece about Cecil [Taylor], Cecil is a huge part of my life. I heard him live for the first time when I was a teenager and so I drew images directly from his music. If you know his music you’ll see the way that I engage with it. That’s my act of interpretation or even individuation in relation to his music. It’s speaking to those things. Anything more narrative than that I find slippery and difficult to be very precise about.

AF: You once said: “If my music could have the perfect form, it would be somewhere between the form of a rock and the form of a rant.” What does that mean and is it still true?

Coleman: Well, one of the problems with most music is that you become aware of its “made” nature. People become so fascinated with that and I’m not so fascinated with the made-ness of things. Like, a rock is just the thing that it is – it doesn’t have some platonic form particularly. And a rant is like when you get in touch with your subconscious: you almost have no filter — you’re just spewing. If you have a rather elegant relationship to language your rants will also have some kind of a form — and I find that form really interesting.

Everything has a form, but it’s not a form that feels like it’s highly calculated. I become disengaged when I have conversations with people who are overly impressed by the complexity of a piece of written music. The complexity of the thinking in a piece that doesn’t seem so complex on the surface: some of Morton Feldman’s or Scelsi’s music often seems much more complex to me then the music of Brian Ferneyhough or Elliott Carter. I am annoyed by people who act like tourists in the land of composition, in the sense that they automatically associate complexity with profundity.

Anthony Coleman working with students. Photo: Andrew Hurlbut.

AF: As a student at NEC, you were a composition major. But after your return as a teacher in 2006 you’ve been in the Third Stream Department. What makes this environment so compatible for you?

Coleman: [As a student], I wasn’t in the Third Stream Department. But I had interfaces with Ran Blake and with other members of the department and I happily participated in many of their concerts. In my first year I was a Jazz Composition major and then I was a Composition major. I studied with people like Donald Martino; so I had a very different experience from that of the Third Stream majors. That department was very small in those days. All that being said, I can’t imagine an environment where I could function so close to the level of an independent creative artist as I’ve been able to do in the NEC’s CI (Contemporary Improvisation) Department. I have an ensemble that often has as many as 16 players; we work on finding the space in between composition and improvisation and have done incredibly creative work.

Some of my students have gone on to be people who are really doing some very innovative things in new music and improvisation and I’m very proud of that. I’ve been very proud of mentoring them. I don’t think I had to do much more than to recognize that they had a lot to offer — in challenging genres that, let’s say, can’t be easily mentored. Because of my background. I was able to find a strong kinship with them.

The flipside of that is there have been very talented people that I have not found enough kinship with. But luckily there are so many great people on the faculty that there are opportunities for students to receive a lot of different kinds of feedback. And, what can I say? It’s a beautifully creative environment and, given the fact that it functions inside of the structure of a conservatory, it’s truly amazing how expansive the world of music is here, how so many different kinds of voices and vocabularies are engaged.

Steve Provizer is a jazz brass player and vocalist, leads a band called Skylight, and plays with the Leap of Faith Orchestra. He has a radio show Thursdays at 5 p.m. on WZBC, 90.3 FM and has been blogging about jazz since 2010.

Tagged: Anthony Coleman, big band, Cecil Taylor, Jazz, NEC, Steve Provizer

Great interview! Congratulations, Steve, and thanks so much for initiating this in-depth discussion of so many touchstones of contemporary music with one of its most intelligent and creative forces.