Rethinking the Repertoire #19 — Charles Ives’ Orchestral Set no. 2

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the nineteenth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

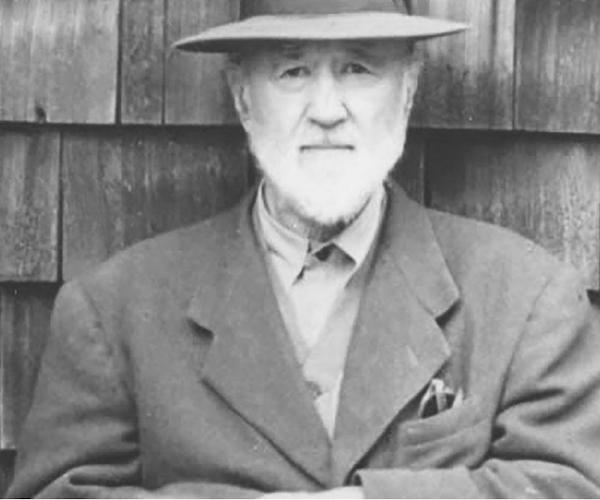

Charles Ives — He continues to stand, after 140-plus years, as the ultimate American Composer.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Few American composer have captured the indefinable essence of what makes American music sound like it comes from – or belongs to – these shores better than Charles Ives. Through a combination of musical quotations; the exploding of harmonic possibilities; inventive use of forms; and sheer, quirky personality, Ives continues to stand, after 140-plus years, as the ultimate American Composer.

Even so, aside from a couple of works like The Unanswered Question and Three Places in New England, his music is not played widely or with particular frequency. Part of this owes, no doubt, to the sheer difficulty of much of it: to learn an Ives score usually means coming to grips with dizzying layers of melodies, asymmetrical rhythms (often subdivided into triplets against quintuplets against septuplets, and so forth), and walls of sound that can too easily be impenetrable.

Then there’s the variability of his output. Ives wrote some truly great music. All four numbered symphonies are superb; the last two, downright visionary. His four violin sonatas are excellent, as is the mammoth Concord Sonata. Ives’ songs are among the most affecting (and sometimes quirky) of any penned in the 19th and 20th centuries. And, from Three Places in New England to the Holidays Symphony, there’s a tally of staggeringly complex and expressive music that sounds like nothing else.

But Ives also wrote a lot of music that was purely experimental or that simply isn’t so good. Both of the string quartets, for instance, arguably fall into those categories, as do individual movements of other works. Of course, an uneven catalogue is no reason to dismiss a composer (just check out Richard Strauss if you’re in doubt of this), but Ives’ case is not helped by the lingering effects of the reputation he held during his lifetime as a musical eccentric. Indeed, even among his advocates, this condescension is sometimes in evidence: look no further than Leonard Bernstein’s late-in-life dismissal of Ives’ music as the work of an “authentic primitive” for an example of this.

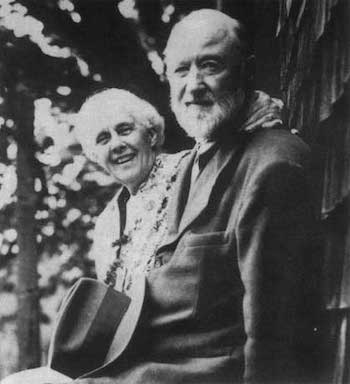

A photo of Charles and Harmony Ives

It should go without saying that such a view of Ives is downright wrong. He was an accomplished keyboardist and composer who mastered the accepted European model with Horatio Parker at Yale – his First Symphony brilliantly subverts the examples of Dvorak and Tchaikovsky then in vogue. That his music was so daring owes mostly to the lasting influence of Ives’ father, George, whose spatial experiments with his Army marching bands (among other things) left an indelible impression on his son.

So did the music Ives grew up with: hymns, patriotic songs, folk music, chief among them. Ives drew on them relentlessly in ways that no major composer before had done, making extensive use of quotation and the layering of various kinds of music, sometimes related, sometimes not. There’s often a physical quality to his music, as well: pieces like The Yale-Princeton Football Game and The Fourth of July endeavor to capture real-life experiences in notes and, in their gestures at least, they often succeed.

The three movements of the Orchestral Set no. 2 draw on these typical Ives-ian sources and allusions. There are made up of hymn tunes, folk songs, intimations of ragtime, and also some intriguing forays into African-American spirituals. And the last two movements refer to specific scenes, one of them unforgettably. They were written independently between 1909 and 1915; only in 1919 did Ives decide to combine them into a single entity. And what an extraordinary piece it is.

Ives called the Set’s first movement “An Elegy to Our Forefathers,” though it was originally conceived as an elegy to Stephen Foster. It’s a collage of familiar (or half-so) tunes, like “Old Black Joe,” “Massa’s in de Cold, Cold Ground,” and, prominently, the spiritual “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” that pass by like a grim procession on a rainy day.

The Set’s second movement depicts a late-19th century revival meeting. It’s anything but sober. Several of the movement’s materials are drawn from his 1902 set of Four Ragtime Dances and the whole thing skewers the syncopations of the popular genre. What’s more, it’s awfully dissonant: Ives loved the sound of untrained voices singing from the heart – often off pitch, sometimes rhythmically askew – and he had an uncanny knack for accurately notating the phenomenon. In this movement, the victim of these affections is the hymn, “Bringing in the Sheaves.”

It’s in the finale where the Set packs its greatest punch. Ives’ subtitle, “From Hanover Square North, At the End of a Tragic Day, The Voice of the People Again Arose,” refers to a sudden, communal outpouring Ives observed on May 7th, 1915, as New Yorkers reeled from the news of the sinking of the R.M.S. Lusitania off the coast of Ireland. As Ives recalled it in his Memos, he was waiting among a rush-hour crowd to commute home for the weekend when an organ-grinder nearby started playing.

Some workmen sitting on the side of the tracks began to whistle the tune, and others began to sing or hum the refrain. A workman with a shovel over his shoulder came on the platform and joined in the chorus, and the next man, a Wall Street banker with white spats and a cane, joined in it, and finally it seemed to me that everybody was singing this tune. They didn’t seem to be singing for fun, but as a natural outlet for what their feelings had been going through all day long. There was a feeling of dignity all through this. The hand-organ man seemed to sense this and wheeled the organ nearer the platform and kept it up fortissimo (and the chorus sounded out as though every man in New York must be joining in it). Then the first train came and everybody crowded in, and the song eventually died out, but the effect on the crowd still showed. Almost nobody talked – the people acted as though they might be coming out of a church service. In going uptown, occasionally little groups would start singing or humming the tune.

Now what was the tune? It wasn’t a Broadway hit, it wasn’t a musical comedy air, it wasn’t a waltz tune or a dance tune or an opera tune or a classical tune, or a tune that all of them probably knew. It was (only) the refrain of an old Gospel Hymn that had stirred many people of past generations. It was nothing but ‟In the Sweet By and By.” It wasn’t a tune written to be sold, or written by a professor of music – but by a man who wanted to express an experience.

This third movement is based on this, fundamentally, and comes from that “L” station. It has secondary themes and rhythms, but widely related, and its general makeup would reflect the sense of many people living, working, and occasionally going through the same deep experience, together…

In Ives’ compositional reworking of the experience, an off-stage chorus makes its only appearance in the Set, intoning the opening phrase of the Te Deum (“We Praise Thee, O God,” etc.) before a rhythmically fractured and sonically distant instrumental ensemble strikes up music that one scholar described as representing the “background noise of New York rush-hour traffic.” Over this dissonant rustle, the orchestra takes up “In the Sweet By and By,” both the verse and chorus, though the hymn is fragmented, with strands of its tune trailing off and other, different but related, melodies intruding. Over about five minutes, through a process of layering textures in an increasingly dense web, the music’s tension builds and, suddenly, releases its pent-up energies in an explosive statement of the hymn’s refrain. It’s a moment of extraordinary release: intense, thrilling, heartfelt. And then it’s over. The crowd disperses, the train leaves the station; all that remains is the background noise of the city, humming incessantly away.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.