Rethinking the Repertoire #16 – – Franz Liszt’s “Dante” Symphony

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the sixteenth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

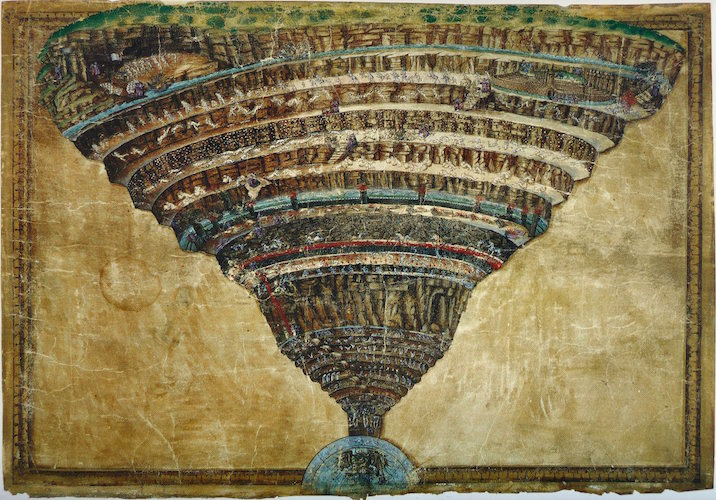

Sandro Botticelli’s “La Carte de l’Enfer”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

There are no two ways around the fact that Franz Liszt’s Dante Symphony is a problematic piece. First of all, there’s the question of whether or not it’s really a symphony. Its two movements are basically a pair of symphonic poems, each depicting, respectively, scenes from Dante’s Inferno and Purgatorio, the first two parts of The Divine Comedy. While both movements are, essentially, in ternary forms, they’re quite free. Nothing but Liszt’s title ties them to the symphonic tradition and both can be performed separately.

Related to this, there’s the difficulty of the music’s structure. Dante’s two movements are unwieldy and unbalanced. The first, cliché-ridden as some of its gestures may be, is one of Liszt’s most progressive episodes. The drama is nonstop. His melodic writing is often sweeping. The melding of motivic ideas, Beethovenian. And the scoring…well, if it doesn’t top Berlioz, Strauss, or Mahler, it surely equals all three of them at their respective primes.

But is the second movement – static and scrupulous – too much the opposite? Did Liszt, like Berlioz before him in La damnation de Faust, wear out his creative resources depicting the terrors of hell? Purgatory, by definition, is surely less exhilarating. But so chaste?

And what to do with the ending? The closing “Magnificat” alludes to the final section of Dante’s triptych, but there’s a certain incompleteness present, as well. Were Wagner’s doubts about Liszt’s abilities to portray the wonders of Paradise well-founded? Is the lack of a full “Paradiso” movement a crippling flaw?

Despite these complications – not to mention a sometimes very unflattering critical reception (George Bernard Shaw memorably said that the piece may as well depict “a London house when the kitchen chimney is on fire”) – what is it about the Dante Symphony that warrants putting it in this survey of underrepresented symphonic music.

First of all, let’s start with the obvious: it’s rarely played. Locally, the Boston Symphony Orchestra hasn’t performed it at Symphony Hall since Christmas Eve 1921 (with Pierre Monteux on the podium; most recently, Kurt Masur led it at Tanglewood sixty-one years later in 1982). A bit further afield, Masur also led the New York Philharmonic’s most recent performance, in 1999 (before that, it was Michael Gielen in 1971 – and then Josef Stransky, also in 1921).

Is that justified? Some seem to think so: after hearing the Chicago Symphony play it in April 2017, Lawrence Johnson called the 25-year hiatus between performances “about right,” and maybe there’s some merit to such an approach: after all, a piece shouldn’t wear out its welcome. But fifty years? A hundred? That strikes me as a bit much.

Part of the reason for this is because Liszt so clearly identified with the music’s subject matter. And why wouldn’t he? An infernal first movement followed by a spiritual meditation – these are themes that perfectly mirrored the two halves of Liszt’s psyche and life, the worldly playboy and the mystic abbe.

What’s more, the deeply personal nature of the music’s narrative drew some extraordinary music from Liszt’s pen. Now, he had, in 1849 written a spectacularly difficult Dante Sonata, also inspired by The Divine Comedy. There are some shared connections between the Sonata and the Dante Symphony of 1857: both alternate harmonic areas, for instance, of D minor and F-sharp major (in the Symphony’s first movement); the “Purgatorio” second movement carries the key relationships further until everything culminates in the “Magnificat” in B major. And the wild character of the Sonata – both its unpredictable structure and its inventive writing for keyboard – are echoed in the “Inferno” movement of the Symphony.

So, what of the distracting musical difficulties both movements present?

Well, to begin, with Liszt, more than with just about any canonical, 19th-century composer, the distance between the sublime and the banal can be no more than a single breath. Liszt was no harsh self-critic like Brahms. Quite the opposite: he wrote, and wrote, and wrote some more. Then he published it all. In Liszt, the sacred and profane, bombast and transcendence, visionary and commonplace, coexist – and, to get a full measure of the man (and his music), you can’t pick and choose one over the other.

Now, are these Blake-ean contrasts as detrimental as they might seem? Sometimes it seems they are: the Piano Concerto no. 2 is, for all its glitter, almost unrelievedly trivial. Even the Dante Sonata can push the boundaries of technique for technique’s sake.

But the Dante Symphony? I don’t think so. Here’s why.

First of all, it’s totally idiosyncratic. You hear this from the Symphony’s very first bars, which hammer out the syllabic rhythms of the inscriptions above Dante’s Gates of Hell. It’s there, too, in the pages of asymmetrical meters that make up the first movement’s middle part. Then there’s Liszt’s handling of the materials of the second movement, which, for all their moments of pause, craftily (and subtly) weave the important motives – the sensuous theme for Francesca da Rimini and her lover, Paolo; the descending “hell” figures; and so on – of the first movement into its construction. If Liszt’s conception of how to pace the Symphony’s drama might not have always been spot-on, the technical skill he displayed in his writing here is never short of inspired.

Composer Franz Liszt — he could be a profoundly forward-looking musician.

That’s true, too, of his handling of the music’s harmonic language. Just about everything is richly chromatic – the whole first movement is essentially an incessant trope on a full chromatic scale, after all. But the second movement’s diatonicism has more to it than initially meets the eye: its rich chorales that pop up like refrains anticipate the harmonic ambiguities of late Wagner, particularly Parsifal.

Then there’s Liszt’s handling of the orchestra in the Dante Symphony, which rarely fails to dazzle. Of course, he was a brilliant orchestrator: the few pieces of his in the canon (above all, Les Preludes) attest to this. But the breadth of colors Liszt drew from the ensemble in the current piece – from the stern brass mottos at the beginning that are punctuated by bass drum/cymbal blasts to the tender writing for clarinets and bassoons in the first movement’s middle part to the austere fugue about a third of the way into the second movement – are exceptionally vivid and fresh. Wagner surely thought so: just listen to what he stole from the Dante (and Faust) Symphonies in his last spate of operas.

Lastly, there’s the visionary aspect of the music. As was noted above, Liszt wasn’t always the most sober-minded of artists: he was fully capable of tossing-off the trite keyboard piece (and bigger). But he could also be a profoundly forward-looking musician. The Faust Symphony, a psychological portrait in notes of the main figures in Goethe’s novel is one of the finest examples of this tendency. Equally remarkable are the short Bagatelle sans tonalité and La lugubre gondola. In its passionate intensity and its sincerely devoted character the Dante Symphony ranks with these innovative works.

And, for all the hand-wringing about its qualifications, the Dante Symphony is also significant for its fresh approach to symphonic form. At the time it was written (in 1857), the symphony was a highly flexible genre. Berlioz, Mendelssohn, and Schumann all toyed with it: forms, content, programmatic qualities (or lack thereof) – everything was fair game. We saw this trend at the very beginning of this series. Here it recurs.

So, yes, there’s little that’s conventionally “symphonic” about the Dante Symphony, save for the use of the orchestra. The musical motives are anything but abstract. There’s little by way of traditional symphonic development. Liszt’s introduction of a chorus at the end might vaguely recall Beethoven. But the effect is wholly different from that found in the “Ode to Joy” and still, at this point in the genre’s history at least, the feat is a pretty rare occurrence.

In all then, the Dante Symphony is a special piece. Sure, it’s imperfect – the lack of a “Paradiso” movement is a shame – and sometimes shallow. But, in the right hands at least, it well exceeds the sum of its parts. Don’t take my word for it, though: check it out for yourself and see what you think

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Dante, Dante Symphony, Franz Liszt, Inferno, Paradiso, Purgatorio