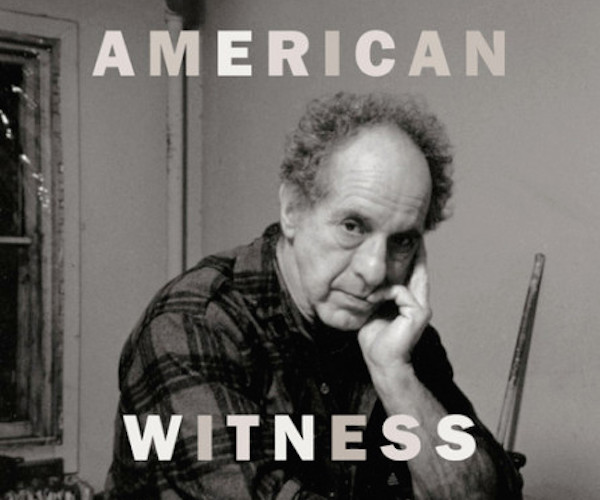

Book Review: “American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank”

Robert Frank had dared overturn the central conceit of the great photographs of the Farm Administration 1930s; that the poor were noble creatures.

American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank by R.J. Smith. De Capo Press, 337 pages, $35.

By Gerald Peary

I have the greatest respect for veteran journalist, R.J. Smith, who previously wrote a well-regarded biography of musician James Brown, attempting the same with photographer and filmmaker, Robert Frank. But despite a wealth of research and interviews, Smith never quite brings his subject into focus in American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank. Could anyone?

This is a hard, tough, unsentimental man who has never cared an iota about fame and reputation or explaining himself. He’s 90 now, and as prickly and ill-tempered as ever. When Smith approached him on the New York streets about cooperating with his book, Frank smiled and said, “Good luck.” He even shook Smith’s hand before walking away. “You caught him on a good day,” said Frank’s friend, Jim Jarmusch. But no assistance, no career interview. And that damages the book, because American Witness relies completely on secondary sources.

Wouldn’t it be amazing for Frank to let his guard down and recall the circumstances behind the masterly photographs in his 1959 classic, The Americans? Or talk openly of his fractious partnership with the Rolling Stones for whom he shot the film, Cocksucker Blues? Or to speak of his broken friendships with Walker Evans and Jack Kerouac, or, rare for the misanthropic Frank, of his sustained friendship with Allen Ginsberg up to the poet’s death?

Dream on. Robert Frank’s lips are sealed. R.J. Smith is on his own.

Smith does a good job contextualizing Frank’s boyhood in Zurich, Switzerland, between the World Wars, he growing up within the upper-class, educated Jewish milieu. Frank’s father, Hermann Frank, was upright and authoritarian and son Robert rebelled both against going to work in his father’s import business and against the rigid conformity of Swiss life. “Everything not to do, I learned from Switzerland,” he later said. His escape was working as a photographer’s assistant, and then becoming a photographer himself. He found a role model, an uncompromising “art” photographer named Jakob Tuggener, who lived in a basement and took a vow of poverty. For Frank, Tuggener was “a monument as large as William Tell…[He] is a great artist.”

Frank apprenticed with a talented modernist photographer, Michael Wolgensinger, and, in 1946, produced his first portfolio book, 40 Fotos. R.J. Smith argues that it already showed Frank’s intense subjectivity: “What he shows is what he sees—what he sees—for this is not simply a pile of images.” And this from a cousin, describing Frank as already the difficult person he would always be: “As a photographer in Switzerland, he went all over the place taking pictures of people, and he didn’t care about what they thought of him or what he wore—he never cared about anyone.”

Let’s flash ahead through many trips around the world and many photographs to Frank living in New York in the early 1950s and, for once, consciously plotting how to make a career. There he courted Edward Steichen, director of the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, sending him an uncharacteristically respectful cover letter: “Dear Mr. Steichen: These are some photographs I took over a period of years. I would like very much to know what you think of them.” Frank’s feigned politeness paid off. Steichen met with him and decided to exhibit his work at MOMA, including a series of images for Steichen’s super-hit show “The Family of Man.”

There was little gratitude from Frank, only contempt for Steichen’s brand of soft, crowd-pleasing photography. “I love to bite the hand that feeds me,” said Frank, who also bothered Steichen for a Guggenheim recommendation. And that hand-biting applied not only to Steichen but to Frank’s road partner and compatriot, Walker Evans. Frank might have respected Evans, but not enough not to reject Evans’s thoughtful introduction to The Americans. Frank commissioned a hotter and trendier one from America’s new sensation, On the Road author Jack Kerouac.

The Americans. The most influential photography book ever. “A degradation of America!” complained MIT’s mandarin photographer-in-residence, Minor White. True, but what a degradation! I wish that author Smith had made the obvious point about Frank’s sad, depraved road photos of the USA. He had dared overturn the central conceit of the great photographs of the Farm Administration 1930s; that the poor were noble creatures. For Frank, poverty made people venal, ugly, angry, ignoble. That’s what he showed, with a tough-love compassion, coast to coast in The Americans.

Frank’s life since? A retreat from The Americans, based on his revulsion about success. For many many years, he stopped taking photographs altogether, hoping people would forget about his work and also not bother him. When he returned to photographic images in the 1970s, they were conscious attacks on beauty. Smith describes them: “Pictures within pictures, frames within mirrors, broken containers. Frank’s work of the later 1970s hemorrhages art.” More than once, Frank spent time in his studio driving nails into selected negatives.

There was torment and unhappiness also in his personal life. His first marriage, to Mary Frank, ended in divorce after he had repeatedly cheated on her. He was neglectful of his children; his daughter, Andrea, died at 21 in a plane accident while his son, Pablo, was a suicide at 43. Frank did find repose with his second wife, June Leaf, who has loyally followed him every year to months of retreat at a home by the rough sea in Nova Scotia. The rest of the time they reside in the Village on Bleecker Street. He might not want it, but sale of his photographs has made Frank a millionaire.

Since the 1960s, Robert Frank has been a prolific indie filmmaker associated with Jonas Mekas and the American Underground. His most famous work was made early on: Pull My Daisy, co-directed by Alfred Leslie, an improvisation with an all-star beatnik cast and a Kerouac voice-over. His many films since, aptly described by Smith, are barely screened or never seen. Not that Frank frets about it. Says Smith: “As time went on, Frank cared less about people being able to see his work.”

Is he a good filmmaker? I wish I knew. When will there be a Frank retrospective?

Here’s a typical kamikaze Robert Frank story that a local projectionist told me. A few years ago, Frank came to Cambridge to speak with his rarely shown Cocksucker Blues, his behind-the-scenes documentary of the sexually active Rolling Stones on tour. Just before the sold-out screening at the Harvard Square Theater, Frank had a mental fit and decided he didn’t want the film shown after all. The projectionist I know screened it anyway, locking the projection booth while Frank pounded on the door demanding that Cocksucker Blues come to a halt.

Afterwards, Frank disappeared into the night, becoming inaccessible per usual. Explained Emilio de Antonio, “It came easy to him because he disliked so many of the people who… might have been able to help him.” Hooray for The Americans, but what a pill of a person! Walker Evans sums him up: “a deft, coruscating artist spitting bitterness, nihilism, and disdain.”

Gerald Peary is a retired film studies professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess.

Tagged: American photography, American Witness: The Art and Life of Robert Frank, R.J. Smith