The Arts on Stamps of the World — November 28

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

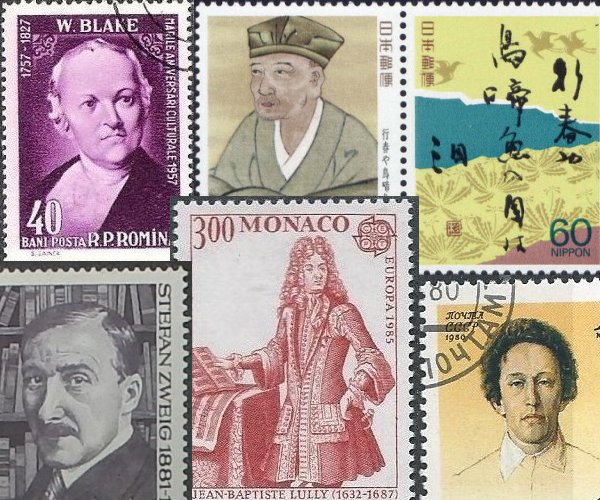

Born on this date were William Blake, haiku master Bashō, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Anton Rubinstein, Alexander Blok, and Stefan Zweig, an impressive and eclectic body of creators.

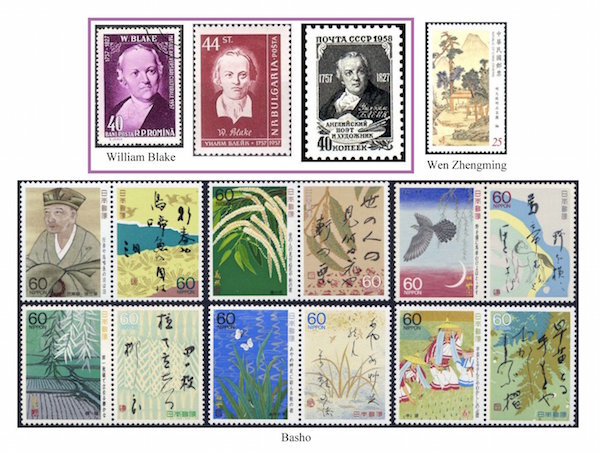

The great English poet and artist William Blake (1757 – 12 August 1827) was a visionary whose works in words and images seemed to step outside his own time. I find it rather surprising that none of his paintings or drawings seems to have found its way onto a stamp, and you may find it bewildering that there is no British stamp honoring Blake, but he has been thus honored by Romania, Bulgaria, and the Soviet Union! Blake’s texts have been set by such composers as Benjamin Britten (most famously in the third section of his Serenade, “Oh, rose, thou art sick”), Vaughan Williams (Ten Blake Songs of 1957), Griffes, Ireland, Ulysses Kay, Walton, and William Bolcom in the huge collection Songs of Innocence and Experience. Boston-based composer Scott Wheeler set Blake’s “Heaven & Earth” in 2008.

The Chinese consider the Four Masters of Ming painting to be Shen Zhou (1427-1509), Tang Yin (1470-1523), Qiu Ying (c1494-c1552), and Wen Zhengming (November 28, 1470 – 1559). It seems that Wen is the only one whose birth date we know. He was born Wen Bi and began studying under the aforementioned Shen Zhou in 1489. As a poet, Wen is also placed among the “Four Literary Masters of the Wuzhong Region”. The stamp, issued by Taiwan just last year, shows Tasting Tea.

And on the subject of Asian poets, we have one of the titans in the field, Matsuo Bashō, born 1644, who died on this date in 1694. In childhood he served a master who engaged him in the writing of collaborative haikai no renga poetry. The opening sequence of this form is what today we call haiku. Bashō became famous while still young and turned to teaching, but found his life unrewarding and gave it up for wandering. It may be that the early death in 1666 of his partner (in poetry, at least) led to depression. In nature Bashō found his inspiration. Beginning in 1987 Japan issued a couple of large sets of stamps in pairs, each pair consisting of a haiku and, presumably, a relevant illustration. The first pair, for example, shows a portrait of the master with one of his verses. I chose another five examples and would welcome translations.

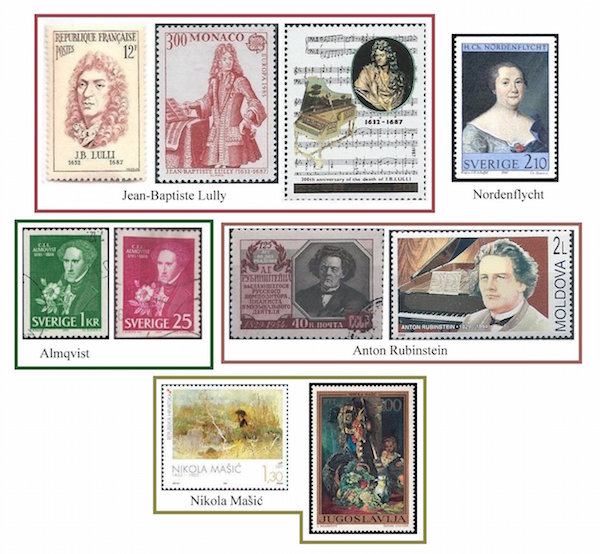

The life of Jean-Baptiste Lully is almost a rags-to-riches story. His father was a milliner (not exactly rags), and by the time he was twenty he had become a master of music under Louis XIV, the “Sun King”, at the most resplendent court in Europe. What’s most surprising, perhaps, is that Lully was not French by birth. He had been born (28 November 1632) in Florence, learned violin and guitar and dancing, and caught the attention of the son of the Duke of Guise, who saw him performing in the street. Off to Paris they went, and Lully never looked back. He was named royal composer for instrumental music in 1653 and became a French subject in 1661. He collaborated on works for the stage with Molière. The story of his death is unusual: While conducting his Te Deum with a tall staff, Lully struck his foot, which became septic; Lully refused to have the leg amputated, because he did not want to give up dancing, and he died of gangrene on 22 March 1687.

To a great extent self-taught, Swedish poet Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht (28 November 1718 – 29 June 1763) became internationally known with her poem “Important Questions to a Scholar” (“Vigtiga frågor til en lärd“), apostrophizing Ludvig Holberg (his birthday is next Sunday) on the question of reconciling religion and science. She had published poems before this and would do so again on the death of her beloved husband (and former French teacher) just a couple of months after their marriage. Nordenflycht went into a depression and composed “The Soothing Turtle-Dove” (“Den sörgande turtur-dufvan“), but now it was necessary for her to provide for herself, and poetry became her vocation. Her talent was recognized with a state pension. Much of Nordenflycht’s writing was decidedly feminist in tone, for example, “The Duty of Women to Use Their Wit” (“Fruentimbers plikt at upöfva deras vett“) and in her response to the misogyny of Rousseau, Defense of Women (Fruentimrets försvar, 1761). Possibly suffering from cancer, Nordenflycht may have intended to take her own life by swimming in the cold.

We remain in Sweden and in the realm of literature for Carl Jonas Love Almqvist (28 November 1793 – 26 September 1866), who was also a supporter of women’s rights. After studies in Uppsala he became a teacher in Stockholm in 1828, was ordained as a pastor in 1837, but soon gave that up for writing—journalism, novels, poetry, plays, educational texts on arithmetic and Greek, etc., etc. Anticipating Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, he wrote a novel, The Queen’s Diadem (Drottningens juvelsmycke), in 1834 in which the main character is neither male nor female and is loved by both men and women. He followed that shocker with It Is Acceptable or It Will Do (Det går an, 1839), about cohabitation outside wedlock. This sort of thing did not sit well with church and state, but Almqvist’s writing remained influential. Now the plot thickens. In 1851 Almqvist was accused of poisoning a usurer to whom he owed a large sum of money. He took to his heels and wound up in Philadelphia, where he entered into a bigamous marriage. In 1865 he attempted to return to Sweden, but died en route in Bremen. Besides his copious output in words, Almqvist was also something of a composer, having published some Free Fantasies for piano and a set of songs in the 1840s. His half-brother was the grandfather of Dag Hammarskjöld.

Anton Rubinstein, not to be confused with Artur Rubinstein, lived from November 28 (O.S. November 16) 1829 to November 20 (O.S. November 8) 1894. Anton Rubinstein was one of the greatest pianists of the 19th century, a central figure in music history. He founded the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1862 (his brother Nikolai founded the Moscow Conservatory four years later) and was the teacher of Tchaikovsky. When Anton was no older than four, his grandfather ordered the entire family to convert from Judaism to Russian Orthodoxy. Later, Rubinstein turned to Christian atheism. (That, to oversimplify, is a rejection of the existence of God with an embrace of the moral teachings of Christ.) Anton, aged 14, and Nikolai, age eight, played before Tsar Nicholas I and went on tour. In Berlin they met and were supported by Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer. Many years later, Anton made a demanding concert tour (200+ concerts) of the United States. His only private piano student was Josef Hofmann. Anton Rubinstein wrote twenty operas, five piano concertos, six symphonies, and many solo piano works. Many recordings of his music exist, but it is seldom heard in concert nowadays.

Serbian painter Nikola Mašić (November 28, 1852 – June 4, 1902) is represented on a 1997 Croatian stamp with Painter in the Pond and on one from Yugoslavia (1972) with a Still Life. Mašić studied in Vienna, Munich, and Paris and became a drawing professor in Zagreb, then a museum curator. His works are typically pictures of peasant life and pastoral idylls such as Harvesting Wood.

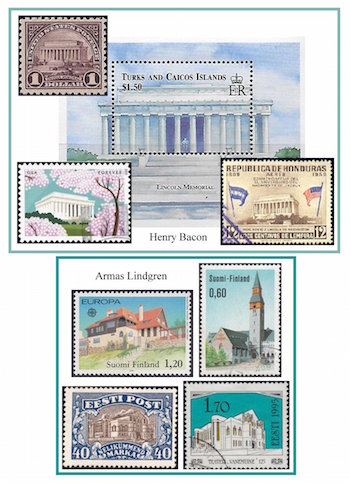

Today’s Collage #3 is devoted to two architects. Far and away the best known work of the American Henry Bacon (November 28, 1866 – February 16, 1924) is the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. (1915-22), which is seen on stamps of the United States, Turks and Caicos Islands, and Honduras. The US stamp at upper left was issued in 1923, the one at bottom left in 2015. Henry Bacon came from Illinois and joined the firm of McKim, Mead & White (MMW) in New York City before completing his education. One of the buildings Bacon would have worked on as a young man was the Boston Public Library. Before that edifice was completed in 1895, Bacon went off to Europe for a couple of years on a scholarship. Most of that time he made careful studies of Greek and Roman architecture. He met his wife, the daughter of a British Consul, in Turkey. He was back at MMW in 1891 but departed in 1897, to start his own firm of Brite and Bacon. In that very year, Bacon was consulted for a new Lincoln Memorial, but in the event work was long delayed for lack of funding. James Brite left the partnership in 1902. Before returning to the Lincoln Memorial project, Bacon had many commissions for public buildings and monuments and collaborated with sculptors Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French, who would create the magnificent Lincoln statue for the Memorial. Bacon also designed a private residence for French, Chesterwood House in Stockbridge. The Lincoln Memorial was finally dedicated in 1922 and thus became Bacon’s last project before his death from cancer two years later.

Finnish architect Armas Lindgren (28 November 1874 – 3 October 1929) was also a painter, but he’s remembered on stamps for three of his buildings, the Hvitträsk residence (1902, at upper left), the National Museum of Finland (1905-16, at upper right), and Estonia’s Vanemuine Theater (1912, at bottom). All three structures were actually collaborations, the first two with Lindgren’s partners in his firm, Herman Gesellius and Eliel Saarinen. This firm had been founded in 1896, a year before Lindgren’s graduation from the Polytechnic Institute of Helsinki, to which he later returned as a professor of art history. (Lindgren’s students included Alvar Aalto.) Further studies took him to Sweden, Denmark, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. The house on Lake Hvitträsk was intended as a studio home for members of the firm of Gesellius, Lindgren, and Saarinen. In 1905, Lindgren left the firm. His partner in the Estonian Theater was Wivi Lönn. The Theater shows up on two Estonian stamps, one from 1927, during the country’s first period of independence, the other from 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Sections of the National Museum have been closed to the public recently, but all the exhibits should be open next year.

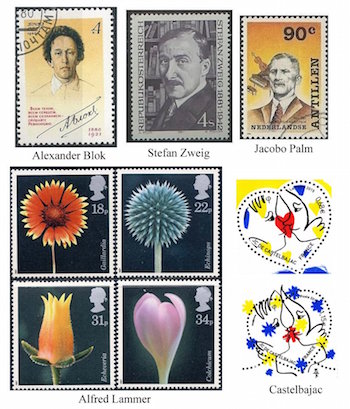

Alexander Blok ([O.S. 16 November] 1880 – 7 August 1921) was a Russian poet who at first was an avid supporter of Communism but who by 1921 had become disillusioned with the Revolution. He was mortally ill, and Maxim Gorky shamed the government into allowing Blok a visa. Molotov himself signed the release, but Blok died three days before it could be delivered. Probably the most prominent musical score set to Blok’s poems is the Shostakovich song cycle for soprano and piano trio, “Seven Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok”, Op. 127. Another cycle, “Beyond the Border of Past Days”, was written by the fine composer Moisei Vainberg. Georgy Sviridov composed a considerable number of works on Blok’s poetry, not only songs, but also a cantata, “Nightly Clouds”, a concerto, “Songs From Hard Times”, and a vocal poem, “Petersburg”. There are also song settings by Rachmaninov (“In the night in my garden”, op. 38 no. 1), Myaskovsky, Glière, Gretchaninov, Edison Denisov, and Nikolay Roslavets.

The great Austrian writer Stefan Zweig (1881 – February 22, 1942) was a novelist, playwright, journalist, and biographer (on Balzac, Nietzsche, Marie Antoinette, and Erasmus, among others). I urge you, if you have not already done so, to read some of Zweig’s brilliant and powerful fiction, for example “Burning Secret” (1913) and “The Royal Game” (1938-41). His most famous musical association is as the librettist for Richard Strauss’s 1935 opera Der schweigsame Frau. Strauss famously refused the Nazis’ demand to have Zweig’s name removed from the opera program on account of his being Jewish. (Zweig had already left the continent in 1934.) Goebbels was miffed and shut down the production after three performances. But Zweig went on to work with Strauss again (at a distance and in collaboration with Joseph Gregor) on the libretto for Daphne in 1937. Other settings of Zweig’s words are by Max Reger and Joseph Marx, who both set the poem “Ein Drängen ist in meinem Herzen“. Henry Jolles, who was also forced to flee Europe in those years, wrote a song, “Último poema de Stefan Zweig“, based on “Letztes Gedicht” (Last Poem), which Zweig had written just months before his death in Brazil.

Jacobo Palm (28 November 1887 – 1 July 1982) was born into a musical family on Curaçao. His grandfather, Jan Gerard Palm (1831-1906), is thought of as the father of Curaçao classical music, and his cousin Rudolf Palm was also a composer, who, like Jacobo, played several musical instruments (keyboard, violin, clarinet, flute…). As an organist, Jacobo Palm played for more than fifty years (1914-68) in the pro-cathedral Santa Ana in Curaçao. He was concertmaster of the Curaçao Philharmonic and founded the Curaçao String Quartet, in which he played viola. His compositional output, which shows the influence of his beloved Chopin as well as a Caribbean, and more specifically Curaçaoan character, consists of piano pieces, organ music for religious services, and songs.

Photographer Alfred Lammer (28 November 1909 – 4 October 2000) was born in Linz, Austria and in his youth enjoyed rock climbing and skiing. He joined anti-Nazi groups and worked in London for his mother’s travel agency in 1934. Although the company failed he remained in England and took up photography. When the war broke out, he signed up for the RAF, even though he did not become a British citizen until 1941. As a Squadron Leader he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross in 1943. With the peace he turned to freelance photography and art teaching. Lammer’s favorite subjects as a photographer included flowers in the wild and stained glass. Four of his flower photos were selected for a British stamp issue in his honor in 1987.

From time to time the French postal service commissions art work from a famous fashion designer, and so it is with these amour stamps conceived by Jean-Charles, marquis de Castelbajac (born 28 November 1949 in Casablanca). He’s better known for his curious clothing ensembles such as the coat of teddy bears Madonna once (once?) wore and that can be seen in the Robert Altman movie Prêt-à-Porter being sported by supermodel Helena Christensen. There’s also a Lego-inspired watch and whatnot.

Today we have three superb writers deserving of stamps (in my humble estimation) but as of yet philatelically deprived: I refer to the American Dawn Powell (November 28, 1896 – November 14, 1965), the Englishwoman Nancy Mitford (28 November 1904 – 30 June 1973), and the Italian Alberto Moravia (November 28, 1907 – September 26, 1990). Too soon for stamphood, but worthy of note, are American writer Rita Mae Brown (born 28 November 1944), Canadian musician Paul Shaffer (1949), American actor Ed Harris (1950), and American comedian Jon Stewart (1962).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.