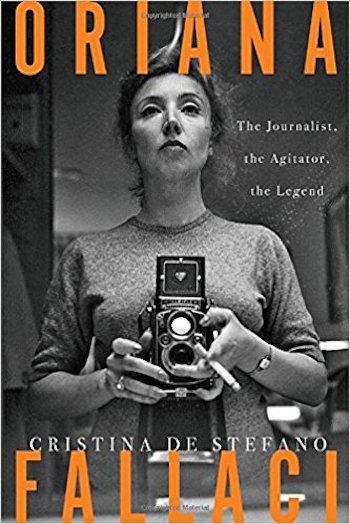

Book Review: “Oriana Fallaci: The Journalist, the Agitator, the Legend”

De Stefano breathlessly tracks the rags-to-riches evolution of a Florentine cabinet-maker’s daughter into a famously bombastic, chain-smoking political reporter and author.

Oriana Fallaci: The Journalist, the Agitator, the Legend by Cristina De Stefano. Translated from the Italian by Marina Harss. Other Press, 282 pp.,$25.95.

By Helen Epstein

“I have never authorized, nor will I ever authorize, a biography,” the late Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci allegedly told an American academic sometime in the 1990s. “My lawyers have always blocked anyone who wanted to write my biography, the story of my life and that of my family. You know my reasons. One is that I would never entrust anyone with the story of my life. Another is that biographers are traitors, just as translators, whether in good or bad faith, always err. Another is that I am obsessed with privacy.”

Who knows what the unequivocally oppositional Fallaci (1929-2006) would have thought of Cristina De Stefano’s jam-packed biography — the tenth book about her? As heedless of convention as Fallaci, writing entirely in the present tense, De Stefano attributes few of her quotes or sources. The copyright page states: “Oriana Fallaci’s quotes are drawn from articles and interviews published in L’Europeo and Corriere della Sera, her books, quotes that have appeared in other books about her, and her private papers.”

I was initially put off by this novelistic approach to biography and confused by its style. Whose words open the book? Is the phrase “This time we’re given, this thing called life, is brief,” Fallaci’s? Is it from an interview? a letter? one of her books? an Italian song or folk saying? When was Fallaci born and did she complete or drop out of university? Were her parents married before her birth, after, ever? Did she have close friends and classmates? What did her colleagues think of Oriana?

“I chose not to interview any Italian journalists,” De Stefano declares breezily in her acknowledgments. “The issue of Oriana’s relationship with the journalistic establishment in Italy is so vast and complex that it merits its own book.” Really? But since I don’t read Italian, I was fascinated by Fallaci as a student and there are only two academic books in English about her, I read on.

Fluently translated by Marina Harss, this book is so full of intimate, dramatic, and fascinating material that one quickly forgets about the lack of footnotes. De Stefano breathlessly tracks rather than thoughtfully analyzes the rags-to-riches evolution of a Florentine cabinet-maker’s daughter into a famously bombastic, chain-smoking political reporter and author whose books were eventually translated into 21 languages.

In the early 1970s, when political reporting was the domain of men and a demure Barbara Walters was occasionally interviewing a “famous woman” for the Today show, Oriana was berating President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu in Saigon, and General Võ Nguyên Giáp in Hanoi. In 1972, she famously interviewed Henry Kissinger (“this too famous, too important, too lucky man”) and elicited his fantasy of himself as “the lone cowboy” that “Americans love” in what Kissinger later characterized as “the single most disastrous conversation I have ever had with any member of the press.” Then she moved on to the Shah of Iran, Deng Xiaoping, Indira Gandhi, Muammar Quaddafi, Yasser Arafat, and Golda Meir. Her attitude was the opposite of deferential. In mid-interview with the Ayatollah Khomeini in 1979, she tore off her chador to make a point about Muslim women. She began her Lech Wałęsa interview, “Has anyone ever told you that you resemble Stalin? I mean physically.”

Her method and results were extraordinary for her time. So was her tough, working-class, speaking-truth-to-power stance. Her interviews were unique and admired by millions of readers as well as journalistic colleagues, including the exacting Christopher Hitchens. At five foot one and 92 pounds, Oriana became famous for such fierceness that, in 1976, the New Yorker ran a riotous parody — “Buon Giorno, Bigshot” — by the late Veronica Geng.

The diminutive, chain-smoking reporter (named after Proust’s Duchesse de Guermantes by her poor but well-read parents) was born in June of 1929 to Tosca Cantini and Edoardo Fallaci. The Fallacis were socialists and active anti-Fascists after Mussolini consolidated his power in 1925. Oriana began attending meetings of the resistenza with her father when she was fourteen; her nom de guerre was Emilia; she learned her first English from two British soldiers – Nigel and Gordon — who had escaped from a POW camp and who hid in her room for a month. In 1944, her father was arrested and tortured, but refused to name names.

“Certain ideas formed during this period stay with her,” De Stefano writes. “The idea of courage, for example, which, for Oriana will always remain the supreme virtue in a man. As an adult, she will find it almost impossible to find a man worth falling in love with.”

Like so many children who become writers, Oriana was an avid reader whose favorite books included the Thousand and One Nights and Jack London’s Call of the Wild. After graduating from the Liceo Classico Galileo she entered the medical faculty at the University of Florence and used her editor uncle Bruno Fallaci’s name to find work at a Florentine newspaper. By 1950, at 21, she seems to have dropped out of college and was reporting the trial of Italian smugglers trafficking in stolen Jewish artifacts. In 1954, after she and her uncle were both fired, she moved to Rome to write about movie stars and socialites for the weekly news magazine L’Europeo.

That year, she talked her editor into sending her on the first flight from Rome to Teheran and, while there, interviewed Soraya, wife of the Shah of Iran. Then she persuaded him to let her report on the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, her first heady experience of war reporting. But her editors then sent her back to the features side of journalism: to Hollywood, where she developed her combative interviewing technique by baiting movie stars; and, in 1961, around the world to report on the condition of women.

That tour of the world established two key touchstones for Fallaci. First, she began a long exclusive publishing relationship with Rizzoli, which first published a book about the women she interviewed and almost all her other books. Second, Fallaci’s encounters with women in Pakistan set off her life-long hatred of Islam. In that book she wrote, “This strip of land where there are no unmarried women, or love matches, and where mathematics are considered an opinion, includes six hundred million people, half of whom, more or less, are women who live behind the darkness of a veil… This sheet, which is called purah or burka or pushi or kulle or djellaba, has two holes for the eyes, or a fine mesh opening two centimeters high and six centimeters wide. The wearer gazes out at the sky and her fellow man like a prisoner peering through the bars of her prison. This prison reaches from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, and includes Morocco, Algeria, Nigeria, Libya, Iraq, Iran, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Indonesia. It is the immense reign of Islam.”

Her feelings about Islam only became more negative over the decades.

In her late 20s, she had a (on her side passionate) largely unrequited love affair with a fellow Italian journalist, involving a miscarriage that may have been a bungled abortion, and a suicide attempt – which she wrote about in her first novel, Penelope at War (1962). Then she identified a different breed of courageous men and began to interview astronauts; her period in Houston became the book If the Sun Dies, published in the U.S. in 1966. Though L’Europeo remained her employer, these and her articles were widely translated, brought her “soft news” period to an end and marked the beginning of her partial residency in the U.S.

In November of 1967, she persuaded the editor of L’Europeo to send her to Vietnam. She was now 38. In Saigon she apprenticed herself to veteran Agence France-Presse journalist François Pelou and became a bona fide war reporter as well as Pelou’s lover. He was married and refused to divorce his wife. Their affair continued even after the war ended in 1975 and he was assigned to Brazil. De Stefano writes that, by that time, Fallaci could choose her assignments and chose to cover one hot spot after another in Asia, South America, and the Middle East, usually interviewing the top honcho. A collection of her interviews until then was published by Rizzoli as Intervista con la storia in 1974 and as Interview with History a year later in the U.S.

“She works tirelessly on the logic of the article,” De Stefano writes. After meticulous preparation, her interviews themselves could last up to six hours and Fallaci often tried to obtain more time with her subject. “She transcribes everything…the puts her text together like a play, cutting and pasting, crafting the rhythm and flow…She considers herself a writer. She argues that her interviews are stories, with characters, surprises, conflict, and, especially, suspense.”

Fallaci’s 1973 interview with Alexandros Panagoulis, the Greek resistance hero who tried to assassinate military dictator Georgios Papadopoulos, led to her third major love affair. She was 47 and known, like the legendary “La Callas,” as “La Fallaci.” Alekos, De Stefano writes, was ten years her junior and “the incarnation of the hero she has been searching for ever since she was a girl fighting in the resistance with her father.” He was traumatized by his imprisonment and torture, and had a large family and an entourage of Greek groupies who got on Oriana’s nerves. Their three-year relationship was tumultuous and, in part, long-distance. Then, in May of 1976, Alekos was killed in a car crash that Falacci believed was an assassination; she determined to write a novel to commemorate him.

By then, she was able to command large book advances. Lettera a un bambino mai nato, her ninth book, became a bestseller, first in Italy in 1975 and then, as Letter to a Child Never Born, in the U.S. The author, who had experienced at least two miscarriages, typically wrote out her conflicted feelings of devotion to her work and ambivalence about the prospect of becoming a mother, landing her in the middle of the abortion wars.

Less than a year after Panagoulis died, Fallaci’s mother died of cancer. Fallaci holed up in her Tuscan compound in Casole to write and rewrite a 600-page book about him. She had tried to convince Panagoulis to write it himself and he had begun but found that he was unable to write about his torture. Titled Un Uomo and published in 1979, Fallaci regarded the book as a memorial to her soulmate.

Now 50, she had fulfilled her childhood dream: she was an established author who took journalistic assignments only when she wanted to fly somewhere or meet someone interesting. She decided to interview Khomeini, Ariel Sharon, Walesa, and Deng Xiaoping. In 1982, after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, she flew to Beirut to interview Italian soldiers who were part of the multinational peace-keeping force there.

“She takes a liking to a sergeant by the name of Paolo Nespoli who is almost half her age,” writes De Stefano. Nespoli was assigned to escort Fallaci around Beirut. Her novel Un Uomo was one of his mother’s favorite books and a middle school girlfriend gave him Fallaci’s volumes on astronauts. The couple fell into an unconventional romance and, in 1985, Paolo moved into Fallaci’s New York apartment and remained for four years while she worked on her 800-page novel inspired by Lebanon, titled Inshallah. “Almost 20 years before September 11,” De Stefano writes, “Oriana suggests that radical Islam will expand beyond the Middle Eastern arena and confront the West in a much wider war.”

Fallaci had by then become as much of a New Yorker as a Florentine. After 9/11, her long-brewing rage against Islam was further galvanized. She called up the editor-in-chief of the prestigious Corriere della Sera and proposed a piece on the attack. She herself titled the blistering polemic against radical Islam and what she saw as Europe’s cowardice in its wake “The Rage and the Pride” and though it, too, was published as a book that became a bestseller, it brought her career as a leftist to an end.

Oriana Fallaci — many women journalists and non-fiction writers saw her as a modern Antigone, Joan of Arc, Cassandra.

De Stefano does not pay much attention to Fallaci’s final years, now seen as a right-wing extremist and ill with the terminal cancer that killed both her parents. The Rage and the Pride, followed by The Force of Reason and The Apocalypse, argued that Europe was becoming “Eurabia,” “a colony of Islam.” Margot Talbot, in the New Yorker, wrote shortly before Fallaci’s death in 2006, “The rhetoric of Fallaci’s trilogy is intentionally intemperate and frequently offensive: in the first volume, she writes that Muslims “breed like rats”; in the second, she writes that this statement was “a little brutal” but “indisputably accurate…” Much of the Italian intelligentsia shunned her. (The German press was highly critical, too.) A 2003 article in the left-wing newspaper La Repubblica called her “ignorantissima,” an “exhibitionist posing as the Joan of Arc of the West.” A fashionable gallery in Milan recently showed a large portrait of her—beheaded.”

Fallaci was sued in Italy, France, and Switzerland as her three books became international best-sellers; intellectuals and fellow literati denounced her, but the reader will learn little about that long and bitter period of controversy from De Stefano’s breezy biography. Perhaps the author was exhausted by writing Fallaci’s life. Perhaps she was not all that interested in Fallaci’s political evolution. At any rate, De Stefano ends the book with Fallaci’s meeting Pope Benedikt XVI and preparing for her funeral to the sound of bells.

I understand why. For many women journalists and non-fiction writers, Oriana Fallaci was a modern Antigone, Joan of Arc, Cassandra. Being Italian helped; so did being a child of the Italian Resistance. She had doting parents who encouraged her independence; she wore pants, lived and loved hard. She did what she wanted; slept with whomever she wanted, and succeeded without, it seems, compromising her lofty ideals.

Her books have not held up as well as her legend. Skimming through Interview with History, I found her writing tendentious and the interviews themselves dated. Her writings about Islam are generally regarded as racist, but they are of a piece with her always over-the-top style. Oriana spared no one with any modicum of power her scorn; De Stefano’s biography is a fascinating albeit less than psychologically profound read about an extraordinary person.

Helen Epstein is a veteran journalist and former NYU journalism professor. Author of Children of the Holocaust and Where She Came From, she will publish the third book in the non-fiction trilogy: The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma in January. More here

Tagged: Cristina De Stefano, Culture Vulture, Oriana Fallaci, Oriana Fallaci: the Journalist, Other Press, the Agitator