Jazz Preview: Bassist Gary Peacock Plays What He Doesn’t Know

Veteran bassist Gary Peacock doesn’t differentiate between experimental and straight-ahead jazz.

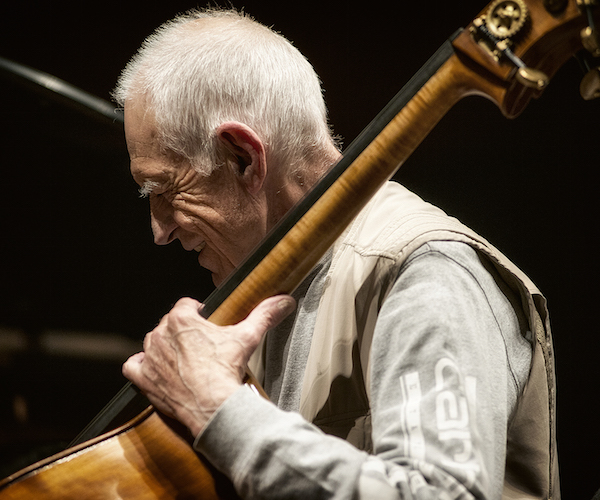

Bassist Gary Peacock. Photo: © Caterina di Perri / ECM Records

By Ken Bader

Jazz greats have long held Gary Peacock in the highest esteem. Over the course of his 60 years in music, Peacock has accepted invitations from, among others, Miles Davis, Bill Evans, Keith Jarrett, and Albert Ayler to join their groups.

One former band mate, drummer Jack DeJohnette, praises Peacock’s “sound, choice of notes, and, above all, the buoyancy of his playing.” Another former collaborator, pianist Marilyn Crispell, calls Peacock a “sensitive musician with a great harmonic sense.”

But when I asked Gary Peacock, now 82, how he would describe his style, well, he just wouldn’t go there.

I’m not after my statement or my identity as a bass player or improviser. It’s not about me. It’s about the music. It’s about my responsibility to be in a particular place that other people can share, enjoy, and feel something.

Peacock’s mastery of the bass is better experienced than explained, as demonstrated in this instructional video from 1999.

Peacock started playing piano as a child and drums as a teenager. He didn’t take up the bass until he was 20.

I was in the military in Germany, and I formed a quintet, playing piano. The bass player got married, and his wife didn’t want him out any more. So I was frantically looking for someone to replace him. The band’s drummer at the time was “Red” Holt, who was the drummer with the original Ramsey Lewis Trio. He said, “You ain’t gonna find a bass player. You play bass.” I said, “I don’t want to play bass. I want to play the piano.” And he said, “No, man, I’ll find a piano player. You play bass.” I said, “Red, I don’t want to play the bass.” As it turned out, he found a pianist, and I started playing the bass.

It was a good fit.

I seemed to progress pretty rapidly in a very short time. And since I was stationed in Germany and there weren’t any bass players anywhere, it allowed me to be available to play sessions with different people in Frankfort and the surrounding areas.

When he got out of the army, Peacock headed for Los Angeles.

I had a standing invitation for a scholarship at Westlake College of Music. So I went to the school. They said, “Great. Unfortunately, the school is closing.” That ended my scholarly education. So I had to start looking for gigs right away. At that time in L-A, there were plenty of opportunities for work. So I did a lot of schmoozing, talking to musicians I knew, and meeting more people. And I was doing sessions.

Peacock also did some teaching and, as often happens, learned a valuable lesson from one of his students.

He brought in an album of (free jazz innovator) Ornette Coleman’s music. The minute I saw it, I said, “No no no. Let me have this album before we meet next week, and I will explain to you why this is all bullshit.” So the next day, I got out a legal size notebook and started going through all the pieces. What I came up with was a shock. Number one, Ornette as a composer was brilliant, really unique. The other thing was that he was not paying attention to any particular form or key — all the things that were my security blanket. So it challenged that fixed position I had about what jazz improvisation should be and what the rules are. It created a pivot for me to embrace a much larger musical universe. If you start to play free, there’s no road map, no form, and no harmonic sequences. You have to just rely on the moment, on what the ear’s telling you. It was challenging but inspiring at the same time.

Ornette Coleman’s free spirit nourishes Peacock’s music to this day.

In 1962, Peacock moved to New York, where he met another free jazz pioneer, Albert Ayler. Remarkably, within a seven-month span, Peacock played on Ayler’s ground-breaking Spiritual Unity and on Trio 64, by the far more mainstream Bill Evans. For his part, Peacock doesn’t differentiate between experimental and straight-ahead jazz. “By that time,” he says, “my hearing had opened to the point that I was available for any kind of musical presentation.”

Miles probably said one of the most brilliant, useful, and necessary comments I’ve ever heard. Somebody was recording with him, and Miles looked at him and said, “What I want to hear is what you don’t know.” That is really the key: not playing what you know, playing what you don’t know. To do that, you have to get very quiet inside, listen, and surrender to whatever that particular musical setting is. So it doesn’t make any difference whether I’m playing standards or free stuff, because you’re giving up any kind of fixed positions or attitudes you may have about what it should or shouldn’t be. And to do that, you have to be vulnerable, to be in a place where you realize that what you’re after, you cannot know. It’s not conceivable. But it’s there. It’s the muse. So it’s kind of a switch from the self playing the muse to the muse playing the self.

Peacock had found his muse, and the jazz world was taking notice. In 1964, he filled in for Ron Carter in the Miles Davis Quintet, toured Europe with Ayler, and recorded with pianist Paul Bley.

But later that year, everything changed for Peacock — musically and personally.

I was not in good shape. I was doing a lot of drugs and alcohol, and I was discontented with myself. I happened to meet with Timothy Leary and some of the people who were connected with him, and one of his friends said, “Did you ever try LSD?” So the long and the short of it was I went up to Newton Center (Massachusetts) for a weekend and took acid. The result of that was realizing, number one, that I didn’t know who the hell I was, whereas before, I’d always identified myself as a musician, a bass player. Then, of course, came “Who am I?” I also noticed that this desire to play music wasn’t there anymore. So the question was, what to do. So what I did was nothing. I stopped playing.

Gary Peacock Trio, L to R: Marc Copland, Gary Peacock, Joey Baron. Photo: © Caterina di Perri / ECM Records.

Peacock turned his attention to other pursuits.

I got involved with macrobiotics and felt drawn to Eastern philosophies and medicine. I became a regular practitioner of macrobiotics and eventually moved to Japan for two and a half years, studying the language, history, and Oriental philosophy.

When Peacock returned to the United States, he still wasn’t ready to dive back into music. Instead, he enrolled at the University of Washington in Seattle, where he spent the next four years studying molecular biology.

After he graduated, Peacock went back to Japan to tour with Bley. That’s when he got the itch to return to jazz full-time. In 1983, Keith Jarrett asked Peacock and Jack DeJohnette to join him in what came to be known as the Standards Trio. For the next 30 years, they reinterpreted the jazz repertoire on recordings and concert stages worldwide.

Now, Peacock heads his own trio, with pianist Marc Copland and drummer Joey Baron. Almost all the tracks on the trio’s new album, Tangents, were improvised on the spot, in the studio.

Two exceptions are songs associated with Bill Evans: “Spartacus” and “Blue in Green.”

There’s a character to those two pieces that we all embrace. It’s kind of like a place where we meet musically and that we have a fondness and an empathy for.

Peacock seems highly aware of the limited value of words, at least in connection with music. The way he sees it, you learn to speak words before you learn to play notes, but eventually, the notes express more than the words.

You go through a period of developing skill with your instrument, and you learn about theory, harmony, form, and keys. Initially, you use that information and skill to play. Then, if you continue, you finally reach a point where you’re not satisfied. There are only two ways to go; one way is to go more into theory, concept, and intellectualization; the other way is to realize that what you’re after you’ll never be able to put into words. And if you go in that direction, things open up in a different way. It’s like poetry — trying to say something with words that can’t be said with words. You get Rilke, and Rumi, and “A rose is a rose is a rose.”

Ken Bader has been Senior Editor for NPR, WBUR, and WGBH.

Tagged: Gary Peacock, Gary Peacock Trio, Joey Baron, Ken Bader, Marc Copland

[…] a 2017 interview with Artsfuse, Peacock shared that during his time with the quintet, Davis said “one of the most brilliant, […]

[…] my statement or my identity as a bass player or improviser. It’s not about me,” he told Arts Fuse in 2017. “It’s about the music. It’s about my responsibility to be in a […]

For those of us who came of age in the ‘60’s, our giants of music, our jazz giants, are leaving us. Yet how lovely that individuals such as Ornette Coleman and now Gary Peacock remained alive on the planet so long.

As a fan of Tony Williams when he came to San Francisco with Miles (the clubs couldn’t serve liquor with this teenager in the band – unless they also served food, which was not common),

I was introduced to Gary Peacock by Tony’s album Lifetime.I was impressed by how Gary Peacock listened and gave back to what Tony was reaching for. Gary’s musical ability, personal character and goodness was apparent from that lovely album of youthful hope.

That kind of generosity and belief in each other that is characteristic of jazz musicians is what the world needs now.

[…] there, he told Arts Fuse, “I seemed to progress pretty rapidly in a very short time. And since I was stationed in Germany […]