Book Review: “Love, Madness & Scandal” — Among the Metaphysicals

Johanna Luthman has given us a fascinating look at Frances Coke Villiers’s unique tale of rebellion, examining the plight of one memorable woman during a tumultuous time.

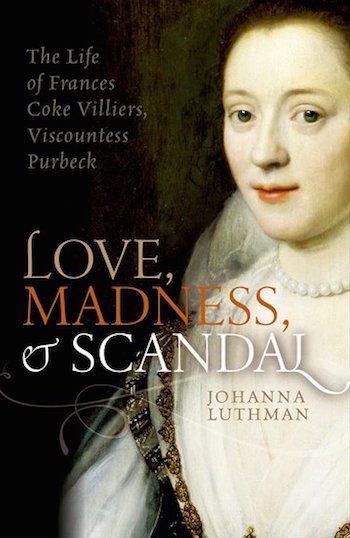

Love, Madness & Scandal, The Life of Frances Villiers, Viscountess Purbeck by Johanna Luthman. Oxford University Press, 216 pages, $27.95.

By Roberta Silman

Towards the end of Shakespeare’s life (he died in 1616) there was an amazing flowering of a new kind of English poetry very different from the Elizabethans and the courtly poetry that had come before. More than a hundred years later Samuel Johnson gave it the name “metaphysical poetry,” writing “[there] appeared a race of writers that may be termed the metaphysical poets.” It was more intellectual, had more complicated imagery, was known for its often mandarin sexual puns and content, and made its greatest impact when recited rather than merely written. This is not surprising because some of its practitioners were churchmen used to giving sermons and proselytizing from the pulpit. The ones most often mentioned as “metaphysical poets” are the great John Donne, George Herbert, Richard Crashaw and Andrew Marvell. Often included were also Henry Vaughan and Abraham Cowley.

The labelling and admiration of these men, who were certainly not a group or a movement when they lived and wrote at the beginning and middle of the 17th century, gathered even more purchase in the 20th century when T.S. Eliot singled them out for praise. The thrust of his criticism was how modern and nuanced they were, how their use of language opened the path to modernism, and how their once obscure poems had real relevance three hundred years after they were written, e.g. Donne’s “No man is an island,” from which Hemingway got his title: For Whom the Bell Tolls.

As the years have passed, I have grown to love those metaphysical poets even more than I did when I was young, so when Johanna Luthman’s biography of Frances Coke Villiers arrived I knew I had to read it. For Frances, who lived from 1601 to 1645, was a rebel who came from a wildly dysfunctional family, married into an equally dysfunctional family and, despite all kinds of opposition from people in high places, refused to lived within the conventions of her time — the very kind of woman who might have inspired some of those gorgeous, sexy poems.

I was not disappointed. In Love, Madness & Scandal, Luthman has written a fascinating account of the life of a woman who belonged to the English aristocracy at the time of King James I (who was England’s first Stuart king from 1603-1625) and his son King Charles I (who ruled from 1625 until his execution in 1649 at the end of England’s great civil war.) In remarkably accessible prose she gives us a portrait of two crazy families, the family Frances was born into and — that of Sir Edward Coke and Lady Hatton — and the family she was forced to marry into in 1617, the Villiers, who included her brother-in-law the Duke of Buckingham, who was the very special favorite of King James.

As Frances’s unhappy story unfolds we learn how young girls in the aristocracy were often used only as pawns to gain wealth for their respective parents. We see how powerless women of the Jacobean Age (the time when King James I ruled) were even if they were high born, and witness how closely the domestic struggles were monitored by the Crown and those close to it, as well as how much depended on royal privilege. We also get voluminous details about the intimate lives of such women — how they often turned to lovers for sexual fulfillment, how they practiced birth control, when they could conceivably have an abortion, how they did or did not nurse their infants, and how difficult it was for them to assert their rights — marital, financial, even emotional — in such a male-dominated society. We learn how adultery was interpreted differently for women than for men.

The second daughter of her father’s second marriage (it was a first marriage for Lady Hatton), Frances was present at arguments and haggling and finally abuse, mostly about money, between her ill-matched parents. By the time she was marriageable, the fighting centered on her and whom she would marry, and because of her father’s position and his ability to get his way, she ended up married to John Villiers, the son of a family even more powerful than Coke or Hatton, with a husband who was mentally ill, physically frail, and impotent. Moreover, once married she was not only ignored, as she had been often in her childhood and adolescent years, but actually abandoned at various junctures by both her father and mother, neither of whom seemed to have any idea of what unconditional love for a child really was.

We get voluminous details about the intimate lives of women such as Frances Coke Villiers — how they often turned to lovers for sexual fulfillment, how they practiced birth control.

Although Frances herself did not leave a trove of paper for posterity, she did write one amazingly artful letter to the Duke of Buckingham in 1622 when she was at the end of her tether after facing years of enforced separation from her husband and money troubles caused by the greediness of her husband’s family and lack of support from her birth family. From that carefully worded missive, in which she entreats her brother-in-law for more just treatment, we get a very good picture of who she was and what she was up against. “For if you please but to consider not only the lamentable state I am in, deprived of all comforts of a husband, and having no means to live of: besides falling from the hopes my fortune then did promise me, for you know very well I came no beggar to you, though I am like so to be turned off.”

As Luthman puts it:

When Frances wrote this letter, she was around twenty-one years of age. She was no longer an insecure teenager, but a tenacious and resilient young woman. After several years of navigating both her increasingly troubled married life—including a sick husband and unfriendly in-laws—and life at courts both foreign and domestic, Frances clearly had found a new confidence, manifested in her appeal to Buckingham. We begin to see the development of the incredible stubbornness and fighting spirit which became an integral part of Frances’s personality in the years to come.

While some women would have simply retreated into religion or embroidery or good works, Frances did what seems quite a logical path, given her young age and her independent nature. She took a lover, Sir Robert Howard, the fifth son of another aristocratic family. Because of his place in the family he was what Luthman calls, “a man at the periphery of power, [who could] enjoy a great deal of freedom” and privilege. And then she did what many young women throughout the ages have done when they fall in love: she became pregnant. The story of her love affair with Robert Howard, the birth of their illegitimate son, also Robert, is full of cloak-and-dagger details, too intricate to recount but well worth reading for the light it sheds on the royal antics of the day, the maneuvering to gain money and respect, and the way the princes of power became part of what in our day would have been a merely private, domestic struggle. It involves flight and kidnapping, lying at its basest, court intrigues, even flirtation with black magic and poisoning, exile, the works.

Just when it all begins to read more like farce than history, King James dies and not long after that, Frances’s enemy the Duke of Buckingham is killed. Power begins to shift and we get a vivid picture of the reign of Charles I, who was not on Frances’s side because he disapproved strongly of adultery and, unlike so many of his royal peers, was a faithful husband. Slowly, through the lens of Frances’s troubled life, we get a picture of how English society and notions of justice were beginning to change. We see the dramatic demise of the royal right of Kings and the rise of a parliamentary government.

Sadly, Frances did not live to see it or enjoy some of its benefits. She died of a local recurrence of The Black Plague in 1645 in Oxford. And she probably never knew about the poems that were being composed all around her by those extraordinary men in the church, poems that are still read with such pleasure. And I doubt, when she was struggling for her existence, that she knew any of the Puritans who left her land first for Leiden and then for America. But how glad I am that Luthman has given us Frances’s unique tale of rebellion, which reveals so well the plight of one memorable woman during that tumultuous time.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.