CD Reviews: Ebony Quartet’s “Unheard” and Martyn Brabbins conducts Vaughan Williams

Ebony Quartet serves up a “must-hear” album of music from between the world wars; Martyn Brabbins conducts, by just about any measure, one of the great London Symphony’s on record.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

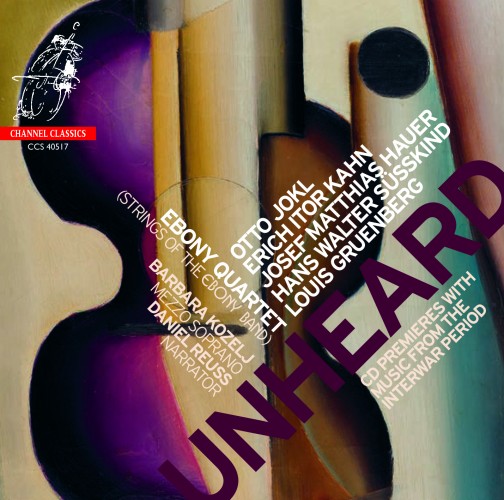

Have you ever heard of Erich Itor Kahn? No? How about Otto Jokl? Hans Walter Süsskind? Maybe Louis Gruenberg? If you’ve studied music theory you might have come across the name Josef Matthias Hauer – otherwise he’s probably a stranger to you, too. These five composers are all represented on the Ebony Quartet’s new album, Unheard, a disc dedicated to music written by German and Austrian Jewish Expressionists between the world wars but not recorded until now. The ensemble, which is made up of members of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, plays them all with impeccable confidence and energy – if there’s a “must-hear” album of music from this era, this is the one.

Kahn’s Fragment eines unvollendeten Streichquartetts (Fragment from an unfinished String Quartet) is the gripping opener. It’s steeped in the language of German musical Expressionism: searching, angular melodies; yearning, unsettled chromaticism; and busy counterpoint all figure prominently over its ten-minute duration. The shadows of Alban Berg and Arnold Schoenberg linger, though the lyricism of Kahn’s writing recalls Mahler a bit more than either of them. Above all, this is music that stands rather impressively on its own two feet: Kahn was only nineteen when he wrote it and the fluency of his technique is staggering. So is the music’s ambiguous expressivity, its searching arguments and quizzical phrases echoing down the corridor of the last hundred years with potent force.

Süsskind is represented by two pieces. The first, Rechenschaft über uns (Accountability for Us) sets spoken poems by the Communist writer Louis Fürnburg in a style that occasionally alludes to the music of Kurt Weill (you can almost think of it as an edgy Weimar counterpoint to Walton’s Façade). Daniel Reuss is the rock-steady narrator. The other one is Vier Lieder, which sets four poems by the German writer Wilhelm Emanuel Süskind (no relation). In them, Süsskind evokes the highly chromatic and rhythmically ambiguous world of Berg’s Altenberg-Lieder with a few unexpected touches (like quarter-tones) thrown in for good measure. Soprano Barbara Kozelj is a powerful advocate for the set, singing with warm tone and an emotional directness not to be taken lightly.

Hauer’s Fünf Stücke für Quartett share the aphoristic directness of much of Webern’s work, but they’re much warmer, tonally. The whole piece is built around a pair of slow movements that are framed by three faster ones. All are strongly shaped and notably brief (the longest movement is just under three minutes); they are the work of a serious composer well worth rediscovery.

The two quartets that fill out the album could hardly be more different. Otto Jokl’s String Quartet no. 2 is a searching, athletic score that seems to be pushing out in multiple directions at once, in the process channeling the expressive vocabulary of Jokl’s mentor, Alban Berg. Gruenberg’s Vier Indiskretionen (Four Indiscretions) are the Jokl’s total opposite: full of charm, whimsy, and humor, they reflect Gruenberg’s enthusiastic embrace of American culture (he settled in California) and insouciance. Together, they close out the disc with a devilish smile.

Throughout, the Ebony’s play these pieces with tremendous vigor and attention to detail. You won’t find – and couldn’t ask for – a better-played or finer-sounding set of belated-debut recordings of any of them.

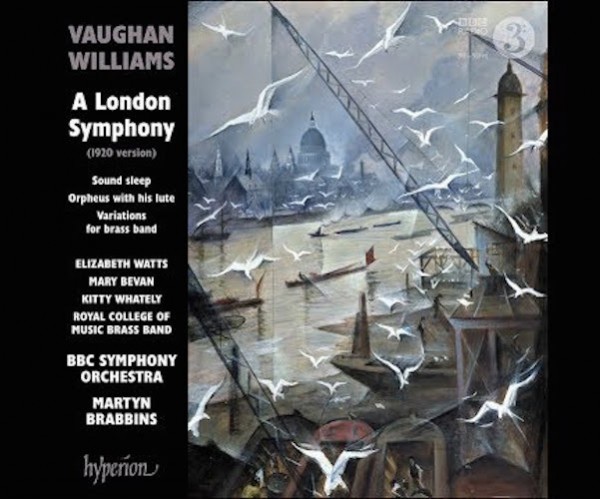

There are a number of fine, new recordings of the symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams on the market today – Andrew Manze is in the middle of a strong cycle for the Onyx label – but there’s something particularly special about Martyn Brabbins’ new account of A London Symphony (and assorted other pieces) with the BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBCSO) for Hyperion. It’s strongly played, yes – but one rather expects that from this conductor/orchestra combination. What makes this disc stand out is the sheer thrill of the music making: these are performances that live fully in the moment and are packed with urgency.

In the Symphony (Vaughan Williams’ no. 2), that means a first movement of tremendous rhythmic vitality and lots of color (the strings’ many tremolo sul ponticello effects always sparkle). Brabbins and the BBCSO’s reading of the second makes as strong a case for it as one of the great slow movements in the 20th-century orchestral canon as I’ve heard. The scherzo (actually a “nocturne in the form of a scherzo,” to quote the composer) is plenty droll while the finale packs an uncommon measure of pathos and mystery, especially over its expanded “Epilogue.”

And, while the big moments rightly pack the heaviest punches, it’s the little, delicate touches that really make this interpretation take off. The slow introduction to the opening movement brims with expectation and the section in the development with string octet blending into the woodwind chorus is played with exquisite delicacy. So, too, are the finely-calibrated woodwind textures that lead to the second movement’s big climax.

While this is, by just about any measure, one of the great London Symphony’s on record, the three pieces that fill out the album are similarly superb. Vaughan Williams’ setting of Christina Rosetti’s “Sound sleep” is a gem, its dulcet lyricism here plumbed by the excellently-balanced and -blended trio of Elizabeth Watts, Mary Bevan, and Kitty Whately. Watts also makes sumptuous work of “Orpheus with his lute,” a short, early-1900s Shakespeare setting.

Vaughan Williams’ brass-band Variations closes out the disc. Written in 1957, just a year before he died, it suggests a composer at the height of his creative powers. Some variations allude to familiar forms or styles (there’s a waltz and a fugue, for instance, plus some hymn-like writing in the final chorale) and the whole thing flows with remarkable clarity and logic. The playing of the Royal College of Music Brass Band is excellent: agile, full-bodied, and marked by a clear sense of musical direction.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.