Theater Review: A Romantic Yet Unnerving “Constellations”

Underground Railway Theater’s production of this touching and articulate play is perfectly lovely.

Constellations written by Nick Payne. Directed by Scott Edmiston. Scenic design by Susan Zeeman Rogers. Costume design by Charles Schoonmaker. Lighting design by Jeff Adelberg. Sound design and original composition by Dewey Dellay. Staged by the Underground Railway Theater at Central Square Theatre, Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, through October 8.

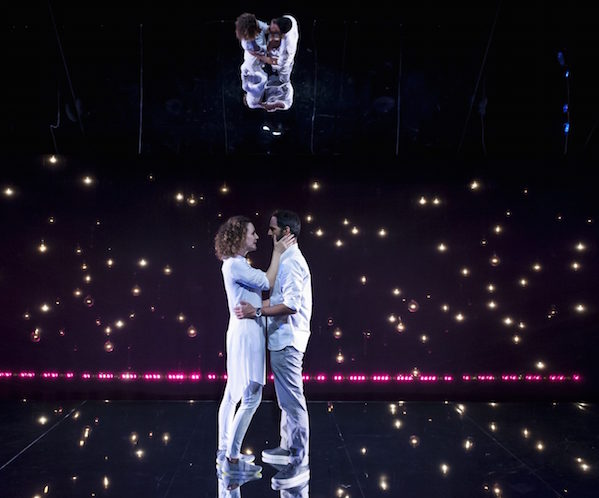

Nael Nacer and Marianna Bassham in “Constellations” at Central Square Theater. Photo: A.R. Sinclair/Central Square Theater.

By David Greenham

The first time Marianne (Marianna Bassham) and Roland (Nael Nacer) meet, it is awkward. In ordinary life we deal with these bumbling first encounters and quickly move on. Nick Payne’s touching and articulate 2012 play Constellations contradicts the quotidian, it is about generating immediate second chances; and third chances; and forth chances, and so on.

In a nifty 80 minutes, we watch the ups and downs and ins and outs of an unlikely pairing of a Cambridge astrophysicist (Marianna), who has an avid interest in the multiverse, and a beekeeper (Roland). They’re not exactly “Average Jane” and “Joe Sixpack,” but the script wants us to catch glimpses of ourselves in these two, and it pretty well succeeds at this challenge. It does so through a series of eight encounters: the awkward meeting, a first date, the admission of an affair, a post-break up chance encounter, the discovery of an illness, and the decision to end a life by euthanasia. Payne nimbly weaves a tapestry of two lives, interlacing multiple paths and possibilities.

“Every choice, every decision you’ve ever made and never made exists in an unimaginably vast ensemble of parallel universes,” Marianne explains early on. To which Roland replies, “This is genuinely turning me on.” He’s right, quantum physics can be pretty sexy stuff, and Bassham and Nacer bring compelling depth and elegant connection to their characters, and to each other.

For those who long for orderly plots, beware. This play is neither linear nor neat. While the episodes generally follow a chronological course, they are interrupted (frequently) with a virtual reset button. Playing with time and structure is not new, and the 33-year-old dramatist has obviously been influenced by predecessors. The opening scene is reminiscent of David Ives’ amusing sketch “Sure Thing” from All in the Timing, his collection of short plays. Pinter’s Betrayal runs a romantic relationship backwards. There are also a number of plays that make use of quantum physics or delve into parallel worlds. What makes Constellations distinctive is that, amid (or despite) the intellectual underpinning, Marianne and Roland’s relationship attains an enormous emotional depth. In an interview about Constellations a couple of years ago, Payne said “I found it quite moving, knowing that someone who had died could be living in a different universe. It felt romantic, yet unnerving, because I’ll never know.” Romantic yet unnerving is the perfect way to describe the mix of mind and feeling in Constellations.

And the Underground Railway’s production is perfectly lovely. There’s plenty of compelling chemistry between Bassham and Nacer: their two star-crossed lovers move, or better yet, float, swiftly through the script’s difficult physical and emotional transitions. Each performer explores the full range of his or her character’s joy and heartbreak. They also skillfully adjust emotional course when the second version of the same scene occurs. A slight change in emotion or story sends the pair off on a slightly different trajectory. Eventually, words fail, and the visceral connection between the two actors becomes even more impressive: a scene in which they speak to each other using sign language is riveting.

Susan Zeeman Rogers’ set is a shimmering, relatively narrow platform with a mirrored floor and a hanging reflective panel. Behind the acting area is a scrim that features a patten of star lights; there’s a row of colorful spots along the ground. Wisely, lighting designer Jeff Adelberg only uses side and back lighting to enhance the mirror-ish nature of Rogers’ set. The result is that the play seems to take place on a platform floating somewhere in space. A change in the colors in the ground row of lights signifies when a new chapter of the story has begun.

Costume designer Charles Schoonmaker dresses the two actors in white or off white clothes, casual enough to allow the maximum movement. Dewey Dellay contributes a soundscape of original music that gently takes us by the hand and guides us among the the stars but, when necessary, it quickly snaps us back down to earth.

Taken at face value, the narrow stage space could easily come off as a sort of pedestrian platform, an MBTA station where people wander aimlessly back and forth waiting for a train. In the hands of director Scott Edmiston, there’s no need to worry about this suggestion of “Heaven’s Waiting Room.” The actors’ movements are beautifully choreographed, balletic. The end and beginning of each new version of a scene is clear, yet we’re really never aware of the blocking. In fact, we almost forget the linear nature of the stage once the play begins.

The seamless and honest collaboration among the director and performers provides memorable moments of humor, romance, and heartbreak. Bassham and Nacer know who should carry the emotional load of the drama and for just how long — they switch back and forth with grace, nuanced acrobats. Edmiston’s outside eye is evident when the two actors suddenly pause, setting up a lovely stage picture that crystalizes the emotion at the core of a scene.

Once again, Undergound Railway’s Catalyst Collaborative@MIT project has paid dividends. It’s inspiring to see intelligent, thought-provoking, and often mind-bending plays on Boston stages. For some of us, our country at the moment seems to have slipped into a parallel universe. (Perhaps a bizarro world?) Constellations reminds us that the smallest actions we take might knock us off our current path, sending us off on a new trajectory. The excitement of that is, of course, the promise of possibility — romantic, yet unnerving.

David Greenham is an adjunct professor of Drama at the University of Maine at Augusta, and is the Program Director for the Holocaust and Human Rights Center of Maine. He spent 14 years leading the Theater at Monmouth, and has been a theater artist and arts administrator in Maine for more than 25 years.