Film Review: “I Called Him Morgan” — A Superb Jazz Documentary

I Called Him Morgan has been lauded as one of the best films of the year, and rightfully so.

I Called Him Morgan, directed by Kasper Collin. On Netflix.

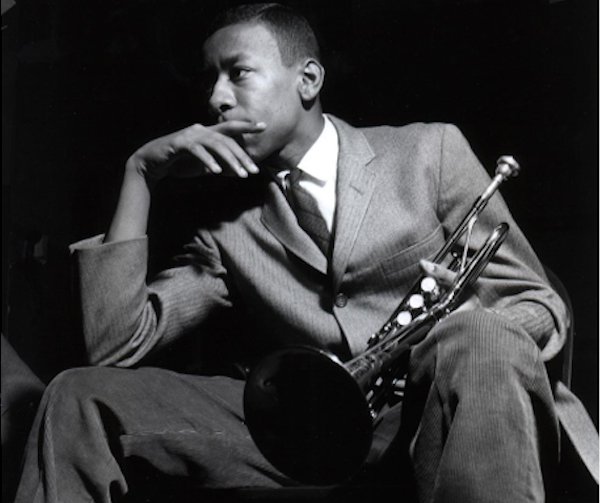

Trumpeter Lee Morgan. Photo: “I Called Him Morgan.”

By Matt Hanson

It’s the best of times and the worst of times for jazz at the movies. Last year long-awaited biopics of Miles Davis and Chet Baker appeared in the theaters, but they didn’t hit the high notes worthy of their mighty subjects. Then there was the hardly Oscar worthy La-La Land, which offered a giddy peak at jazz through a Disneyfied looking glass. Luckily, some new documentaries have come closer to giving jazz its rich cultural/historic due. Recently Chasing Trane, a fine tribute to the life and work of John Coltrane, was released. Now on Netflix there is I Called Him Morgan, Kasper Collin’s engrossing film about the brilliant but damaged life of the great trumpeter Lee Morgan and his common-law wife Helen.

Virtually everything about Lee Morgan was prodigious. Hailing from Philadelphia, Morgan got his big break playing in Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra when he was still in his teens, garnering attention for his soulful but effervescent style. As some of his peers point out, Morgan could tell a story through his solos. He had a stint as one of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers and was the youngest contributor to John Coltrane’s masterful album Blue Train. Morgan seemed to have it all: affable, overflowing with confidence, with boyish good looks and a snappy dress sense. Francis Wolf’s lovely black and white photographs, appearing throughout the film, capture the luminosity of Blue Note’s peak era.

A who’s who of jazz talent, including the great Wayne Shorter and sidemen like Jayme Merritt and Bennie Maupin, testify to Morgan’s skill and charisma. They also marvel at his breakneck pace at making the scene on and off the stage. Among other extravagances, Morgan was fond of racing his sports car through Central Park at midnight. All this high flying would eventually come with a price; Morgan clearly had a self-destructive streak. Like many jazz musicians before and after him, Morgan eventually picked up a nasty heroin addiction that precipitated his brutal fall from grace.

Collin doesn’t solely focus on Morgan’s rise in the music world; he gives equal time and attention to Helen Moore, the scarred but deeply independent woman who would eventually be his salvation. From a late-life interview recorded on a scratchy cassette tape we learn the specifics of her difficult life. After becoming pregnant twice at a disturbingly young age, Moore left her home state of North Carolina to make it on her own in New York City. She speaks curtly of her tenacity, street smarts, and quick mouth, noting that given her circumstances “I had to be.” Her legendary cooking made her midtown apartment a popular hangout for musicians and her fierce privacy was rooted in a tough dignity. She became involved with Morgan when he was at his lowest, strung out and delirious, a shadow of his former self. They never married, but she eventually took on his last name and became his manager, lover, muse, and confidant.

All the interviews remark on what a good couple they were. The story of Lee and Helen unfolds at an unhurried pace; the stories of the people who knew them best generate the narrative. This adds a inviting level of intimacy, aided by candid photographs of Morgan at the apartment they shared and of a blissful residency on the West Coast. Collin doesn’t interject an authorial voice or make judgments, which gives the story an engagingly conversational quality that harmonizes well with the glorious soundtrack.

Morgan’s approach to music stayed fresh as the years passed, beginning with the bebop drenched fifties evolving into the experimental sixties, which eventually gave way to the funkier, Afro-centric seventies. The revolutionary consciousness of the time inspired a newly revitalized Morgan, whose playing gained depth and complexity. He began writing songs in tribute to Angela Davis. He is quoted in an interview critiquing the word “jazz” as a white construct and suggesting a more historically and racially specific alternative: “black classical music.”

Eventually, tensions begin to appear. Morgan starts to spend time with another woman- exactly how Platonic the relationship was remains vague but still probable. Lee and Helen remain together as a matter of course, but start to spend more significant time apart. Trouble begins to brew, but wounds go unattended. Collin (who also directed the too-little seen doc I Am Albert Ayler) capably builds suspense by not rushing to the denouement, letting the story’s entanglements build to their conclusion. What happened one snowy night at Slug’s Saloon in Greenwich Village changed everyone in Morgan’s life forever — the human cost resonated for years.

I Called Him Morgan has been lauded as one of the best films of the year, and rightfully so. The occasional visual flourish — some vintage photography here, a little New York skyline there — is used tastefully and at times gives the film a poetic texture. Hopefully, the movie will help bring attention to Morgan’s extensive and brilliant discography. For now, whitewashed Hollywood seems to be incapable of evoking the exuberance of the music — let alone the vibrant, tragic lives of the musicians who made it. Anyone who loves jazz should be grateful that we have documentaries like this to show us how it’s done.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: Blue-Note, documentary, I Call Him Morgan, Jazz, Kasper Collin, Lee Morgan, Matt Hanson