Poetry Review: Bill Knott’s American Surrealism – A Magic Carpet Ride

Perhaps what makes Bill Knott’s poetry so addictive is his uncanny ability to turn language inside out, flouting and then altering a reader’s expectations of what a poem can be.

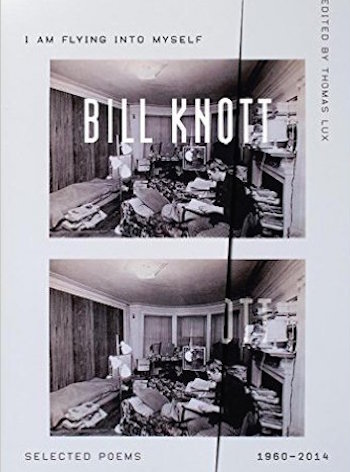

I Am Flying Into Myself: Selected Poems, 1960-2014 by Bill Knott. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 256 pages, $28.

By Matt Hanson

In a 1964 letter recommending interesting young poets to his friend Kenneth Rexroth, James Wright suggested that Rexroth look into “an unmistakably beautiful, deeply fertile, unaffected, marvelous poet…a young man of about 25 years of age who has the wonderfully unpoetick (sic) name of Bill Knott.” Wright clearly had an eye for talent. As the new collection of selected poems I Am Flying Into Myself shows, Bill Knott’s wry, playful, enigmatic but haunting poetry is due for a revival.

The fact that it hasn’t happened yet might be due to the fact that over his long career (he died in 2014) Knott didn’t exactly seek out attention, even within the relatively sequestered world of poetry. Knott was given to bouts of extreme depression and self-doubt; self-promotion wasn’t his style. Stubbornly avoiding being pigeonholed into any school or movement, Knott often railed against the poetry tastemakers — resolutely staying a movement of one.

A radical ethos complicated his approach to publishing. For many years, Knott self-published his books (rejecting covers he considered too showy) and made his poems available online for free, or selling them for the price of printing and mailing through Amazon. Whoever was hip enough to order a copy of his unique poetry always got more than their money’s worth.

Knott’s voice doesn’t strain to impress the reader with its perception and wit, but instead gracefully steps back to work its magic. A good introduction to Knott’s style might be his “Sonnet (To-)”:

The way the world is not

Astonished at you

It doesn’t blink a leaf

When we step from the house

Leads me to think

That beauty is natural, unremarkable

And not to be spoken of

Except in the course of things

The course of singing and worksharing

The course of squeezes and neighbors

The course of you tying back your raving hair to go out

And the course of course of me

Astonished at you

The way the world is not

This poem showcases many (but not all) of the qualities that make Knott’s poetry so remarkable. There’s the open, conversational tone, the informal but confident use of a classic poetic form, the unique turns of phrase (“blink a leaf” and “raving hair”), the pithy statement delivered with clarity and humility, the subtle nods to the political (the “neighbors” and “worksharing”) and the bittersweet juxtaposition of the poet’s tenderness towards his beloved and the world’s blithe indifference to it all.

In his warm introduction the poet Thomas Lux affectionately describes his close friend’s enthusiasm and erudition, acknowledging the somber sides of Knott’s personality as well as his generosity, dedication to craftsmanship, and essential decency. Knott had deep connections to Boston, teaching at Emerson College for twenty-five years and living in a series of dilapidated apartments in Somerville.

Knott certainly knew the pain of the world’s indifference, beginning with an evidently horrific Michigan childhood punctuated by abuse and neglect, followed by miserable stints in the Army and at his uncle’s farm. “All my life I had nothing, / but worse than that, /I wouldn’t share it.” Knott was orphaned at a young age, as described in the moving poem “Christmas at the Orphanage.” His rigorous moral conscience couldn’t have been easy to bear; his disgust at the Vietnam War and America’s complacent exploitation was absolute. One poem entitled “History” starkly lays it out like this: “Hope…goosestep.”

Beginning his long, eccentric career as, in Lux’s words, a “hard-core, blunt-force surrealist” with the publication of The Naomi Poems, Knott made his mark. The odd little book purported to have been written by an obscure poet named after a Catholic saint who committed suicide in his early twenties, dying a virgin. But the obscurantism didn’t fool anyone — if anything it may have added to the volume’s aura of creativity. Hopefully, this edition will spark some publisher’s interest in releasing The Naomi Poems on its own. It would be interesting to see the beginnings of Knott’s American vision of surrealism.

Knott’s poetry is often surreal but his accessibility keeps each poem lively and richly enigmatic. He occasionally switches nouns and verbs, invents new compound words, and uses puns that incorporate writer’s names (such as “Rilkemilky” and “immallarmean”). The bold experimentation impressed his evidently not-insignificant readership — the likes of Robert Pinsky and Yusef Komunyakaa have praised his unique genius.

Knott kept his wry, world weary sensibility sharp throughout his long career, writing many pithy, koan-like aphorisms, often titled simply “Poem,” such as: “Your nakedness: the sound when I break an apple in half.”

Here are a few of my favorites:

“Poem”: “Even when the streets are empty, / even at night, the stopsign/ tells the truth.”

“Bad Habit”: “At least once a day, / every day, / to ensure that my facial/ compatibility with God’s is nil, / I smile.”

“My Life By Me”: “Every autobiography/ longs to reach out/of its pages/ and rip the pseudonym/ off its cover.”

“Minor Poem”: “The only response/ to a child’s grave is/ to lie down before it and play dead.”

Knott’s sense of humor is mordant, self-deprecating, and bends towards the absurd. He isn’t a misanthrope per se, but his incisive intelligence expertly cuts through all linear thinking: “The poem is a letter opener that slices/ a to discover b in which c waits/ and so on until z reiterates/ my metaphor’s acute dullness, its crisis// of belief.” Knott’s poetics can occasionally be difficult, but he isn’t afraid to use clear imagery and language to achieve his effects. “The Sculpture” uses a striking image to deal with issues of poetry as both subjective construct and as mirror up to nature: “We stood there nude embracing while the sculptor/ Poked and packed some sort of glop between us/ Molding fast all the voids the gaps that lay/ Where we’d tried most to hold each other close….”

The love poems are exquisite, though their sense of mortality always looms. Knott’s meditations in “To A Dead Friend” are haunting: “mourning clothes worn/ inside out/ would be white/ if things were right/ if opposites ruled.” Though the specifics of his personal life are somewhat vague (will there eventually be a biography?), Knott’s sensibility never drifted far from a sense of impending tragedy, but there was heroism in his clear-eyed approach to life, an informal protest against the inevitable. The long, rippling lines in the poem “Water” movingly contain variations of the poignant phrase “I am the mourner.” The last poem he ever wrote, “Poem In The Cardiac Unit” heroically fights to keep itself free of cliché even in the direst of circumstances.

Poet Bill Knott. Photo: Poetry Foundation.

I Am Flying into Myself is by far the book I’ve re-read the most times this year, and each time I return to it I notice some fresh new phrase or philosophical insight. A great line like “I walk/ on human stilts” or “even your shoulders are petty crimes” is followed by an amusing poem imagining the galaxy as a deadbeat tenant, evicted by the universe for not expanding fast enough. Perhaps what makes Knott’s poetry so addictive is his uncanny ability to turn language inside out, flouting and then altering a reader’s expectations of what a poem can be.

He’s the only poet I know of who prefers his magic carpet “floating always/ right in front of me/ perpendicular, like a door.” The image in the poem that supplies the title of the collection pivots neatly from an embrace of calm fatalism to imaginative triumph: “Going to sleep, I cross my hands on my chest. / They will place my hands like this. / It will look as though I am flying into myself.” Hopefully, this new collection will inspire readers to be ready to follow along.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: American, Bill Knott, I Am Flying Into Myself, Matt Hanson