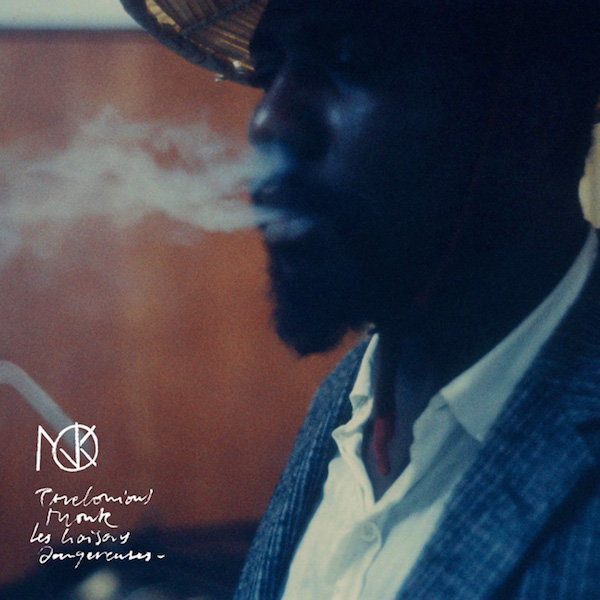

Jazz Review: Thelonious Monk’s: “Les liaisons dangereuses 1960” – Times Retrieved

Everything Monk does here – from the tiny nuances in the statements of his themes to his beautifully cogent solos – show a master thinking carefully about every step and achieving everything he sets out to do.

By Steve Elman

There is an experience common to the first confrontation with groundbreaking art. That first encounter, the experience that can never be repeated, often causes disorientation, even confusion, as you try to fit what you’re seeing or hearing into the existing aesthetic frameworks your brain has established. It’s only after you transcend that familiarity and come to an understanding of the artist’s ideas that a door of perception opens, releasing a thrill, a joy, that is as pure as any you can experience in life. You feel this when you first see Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights.” When you hear Beethoven’s ninth symphony for the first time. When you read Joyce’s Ulysses. It’s there for Ionesco’s Bald Soprano, Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps, Picasso’s Three Musicians.

And it’s there when you hear anything by Thelonious Monk for the first time.

So a CD of newly-discovered Monk in his prime is a precious gift. I thought I’d had my last chance to experience that pleasure in 2005, when Blue Note released Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall, a session from 1957 with both artists captured in the full flower of their collaboration.

But once again I’ve had a taste of new (vintage) Monk – not on the same level of musical excellence as the date with Coltrane, but very good nonetheless, and undoubtedly one of the most important releases of 2017. It’s Les liaisons dangereuses 1960, a French co-production of Sam Records and Saga Jazz. It gives us the first release of the tracks that Monk recorded for the soundtrack of Roger Vadim’s film (which had the same name, minus the year).

Despite extensive discussion about the film in the liner notes, it’s important to set Vadim’s work aside right away. Even though Monk made conscious decisions about which of his tunes to record for the soundtrack after seeing the film, the importance of this release has nothing to do with cinema, and it needs nothing more than the music you hear to give it importance.

Nellie Monk at the Nola Studio sessions. Photo: Courtesy of Arnaud-Boubet, private collection.

Why is it important? Let me count the ways. The session was previously thought to have been lost, but it was discovered stashed in an archive of tapes documenting the work of French saxophonist Barney Wilen. It was superbly recorded by one of the best engineers of the time, Tom Nola, and it is impeccably remastered for this release. It is the only recording of Monk and his long-time sax partner Charlie Rouse in their earliest working quartet, with the rhythm section of Sam Jones and Art Taylor, two musicians of the very top rank. It has one of only two known recordings of Monk free-associating at the piano. It is the only known session where Monk’s two angels, his wife Nellie and his patron, the Baroness Nica de Koenigwarter, are known to have been present. It has the longest Monk rehearsal fragment (fourteen minutes) ever released, a fascinating glimpse into his thinking and his leadership.

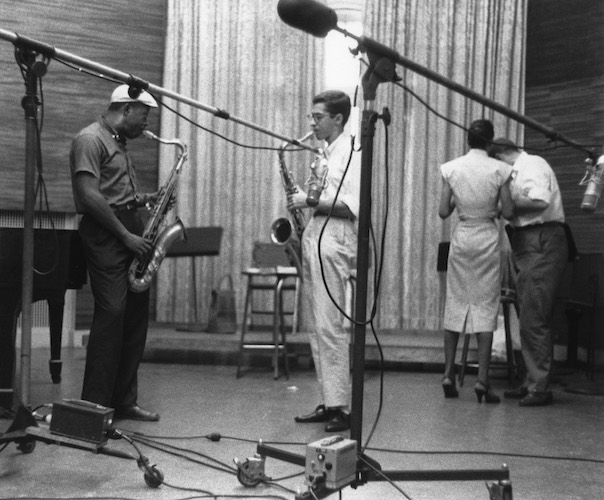

And, by the way, the release is also notable because it contains two tunes where Monk uses two tenor saxophonists for the only time in his career. Unfortunately, Barney Wilen is only voiced in unisons with Rouse, so we don’t know what Monk really might have done with the instrumentation if he’d had the time to work on it.

The CD package is beautiful – two discs in a fold-out sleeve, plus a 56-page booklet that includes many photos from the session. Because this is a French production (c’est toujours comme ceci, n’est-ce pas?), the notes are discursive and prolix. Only the historical context, provided by Monk’s biographer Robin D. G. Kelley, is straightforward in the way an American reader would expect. Nonetheless, it’s worth poring through all of them with a highlighter to pick out the salient details.

The first of the CDs contains the tracks as the original session producer, Marcel Romano, envisioned them for commercial release – a project that never happened. The second has alternate takes, plus the rehearsal fragment of Monk’s recent tune “Light Blue,” about which much more later. Romano chose to include a ham-handed edit of “Well, You Needn’t” in his projected LP, probably shortening the tune because of the time restrictions on vinyl at the time. However, there was no need for the 2017 production team (Zev Feldman, François Lê Xuân, and Frédéric Thomas) to follow Romano’s lead in this case. They have the full take, which is included on the second CD, and they should have scrapped the badly-edited one.

Those are the only cavils I have with the production. The music is another matter entirely. Sam Jones and Art Taylor are strong and comfortable on every tune (except on the one experimental arrangement, “Light Blue”). Charlie Rouse has fresh and intelligent solos, especially on the strongly-swinging tunes (“Rhythm-a-ning,” “Well, You Needn’t,” and “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are”). And Barney Wilen proves that he was not just some French add-on; when he gets a chance to solo, he does better than well.

But, good as the support is, it’s all about Monk, who is in superlative form throughout. Everything he does here – from the tiny nuances in the statements of his themes to his beautifully cogent solos – show a master thinking carefully about every step and achieving everything he sets out to do. Romano, quite wisely, planned to put two solo versions of “Pannonica” back-to-back, and they are a perfect pair. In the first, Monk plays the theme in the middle register of the piano; in the second, he moves to the upper register. Even though the notes are the same, the impact is different – it’s akin to the way that a change in light gives identical subjects different emotional weight in Monet’s paintings. Add to those two the sensitive reading of “Crepuscule with Nellie,” and you come away convinced that Monk must have been inspired by the presence of the two most important women in his life at the time.

So much for the straight-no-chaser reasons that this release is a delight. New or casual appreciators of Monk may very well stop here and go get the CD or its on-line equivalent. (FYI, at least as of this date, the music is not available via any of the major streaming services, so do the right thing and pay for it. You can even get a limited-edition 2-LP set if that floats your boat. Some excerpts are hearable on the Saga Jazz site.)

But true believers will want to dig further, and I have two big reasons for doing so. The first is just a happy coincidence, but it fits beautifully into this world of music, and it will reward your investigation.

Tenor players Charlie Rouse and Barney Wilen rehearsing at Nola Studio (Nellie Monk is standing at right). Photo: Courtesy of Arnaud-Boubet, private collection.

Just three weeks ago, thanks to the advocacy of Justin Freed (a living cultural treasure in eastern Massachusetts and one of the area’s most respected advocates of jazz and film), the Coolidge Corner Theater presented the Boston-area premiere of The Jazz Loft According to W. Eugene Smith, a documentary by Sara Fishko that is rich in music and visual style. I can’t do justice to this outstanding film in this space, but all you need to know right now is that a great deal of it documents the jazz experiments that took place in composer-arranger Hall Overton’s loft space on Sixth Avenue, which Overton shared with photographer Eugene Smith. Smith began recording and photographing what went on there, and his home recordings and beautiful pictures provide much of the core material in the film.

The Jazz Loft includes a twenty-minute segment on Monk’s 1959 collaboration with Overton, with photos and audio of the two men discussing the concept of expanding Monk’s music into a little-big-band format. It also includes chunks of the rehearsals that led to The Thelonious Monk Orchestra at Town Hall, one of Monk’s landmark recordings, and interviews with musicians who participated, including Phil Woods. Hearing Monk and Overton contemplate and then realize the orchestration of Monk’s 1952 solo on “Little Rootie Tootie” is like finding Michelangelo’s sketches for the Sistine Chapel. (For more on the film and some tastes of the Monk segments, see More below.)

This section of the film provides you with an experience akin to the fourteen-minute rehearsal excerpt that closes disc two of the new CD, not only because of the same kind of informality and the insights into Monk’s creative process, but also because the two rehearsals are fairly close in time.

For a full perspective, including some Boston lowlights, here’s a quick chronology, thanks to Robin D. G. Kelley’s indispensable biography, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (Free Press, 2009):

• Late 1957: John Coltrane leaves Monk’s group.

• February – June 1958: Monk has a variety of performances and recordings in which he assesses new talent for his band, including tenor players Sonny Rollins and Johnny Griffin, and bassists Sam Jones and Ahmad Abdul-Malik.

• June 1958: Monk debuts a new quartet at the Five Spot in New York, with Griffin, Abdul-Malik, and master drummer Roy Haynes. He uses the date to teach Griffin the repertoire by ear, frequently interrupting performances to correct the saxophonist and demonstrate the way he wants his tunes to be played.

• August 1958: The Griffin-Abdul-Malik-Haynes quartet returns to the Five Spot, where they record “Light Blue” for the first time.

• September 1958: Griffin leaves the group, replaced by Sonny Rollins.

• October 1958: Rollins leaves the group, replaced by Charlie Rouse.

• January 1959: Record producer Harry Colomby approaches Monk with the idea of doing an evening of his music in a big-band format in concert at Town Hall in New York. Monk and Hall Overton begin working on arrangements for the concert at the Overton-Smith loft. They assemble a band, including Rouse, with Sam Jones on bass and Art Taylor on drums.

• February 28, 1959: The Town Hall concert takes place.

• April 1959: The new working quartet, with Rouse, Jones, and Taylor, is booked into George Wein’s Storyville in Boston (now the basement of the Copley Square Hotel). Monk is unhappy with his accommodations at the Bostonian Hotel at the corner of Boylston Street and Massachusetts Avenue (now a Berklee building), is unable to get a room at the Statler, and decides to go back to New York. At Logan Airport, he becomes agitated. A state trooper takes him into custody and brings him to Grafton State Hospital, where he is treated with Thorazine. He is released a week later in the custody of his wife Nellie and returns to New York.

• July 1959: The Rouse-Jones-Taylor quartet plays the Newport Jazz Festival. Monk is approached by director Roger Vadim and music producer Marcel Romano to do the soundtrack for Les liaisons dangereuses. From July 27 to July 29, the quartet, augmented by French tenor player Barney Wilen, records at Nola Studios in New York, where they rehearse a new version of “Light Blue.”

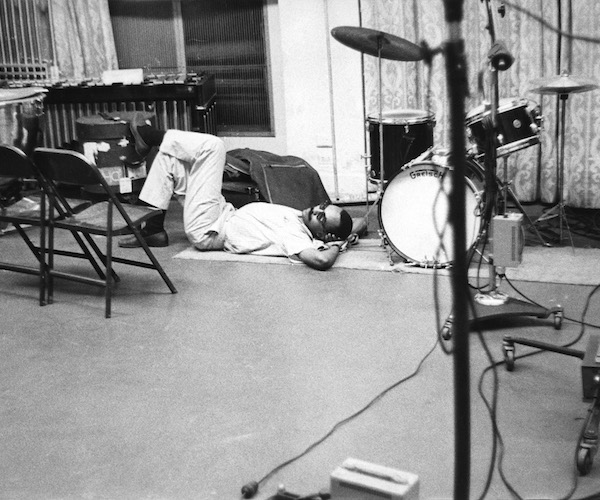

The “Light Blue” rehearsal, like Johnny Griffin’s shakedown in June 1958 and the discussions with Overton in January 1959, was conducted entirely by ear. Apparently, while in the studio, Monk heard something Taylor played and liked it, thinking it would provide a syncopated counterpoint to the theme – a very different feel from the way Roy Haynes played it just a year before. This proved to be a significant challenge for Taylor, and the way this interpersonal drama plays out over fourteen minutes in the new CD gives a real-time journey through Monk’s distinctive thinking – and shows how hard those by-ear rehearsals must have been for Monk’s sidemen.

Art Taylor cools one during the rehearsals at Nola Studio. Photo: Courtesy of Arnaud-Boubet, private collection.

Because the rehearsal has not been remastered to bring up the level of the voices, some of the interchanges between the musicians are difficult to hear. As a service to Monk fans, I have transcribed this track in its entirety and tried to give a brief rundown of each run-through (see More below).

The rehearsal tape begins with Taylor simply toying with some rhythm figures, one of which seems to inspire Monk. He envisions that Taylor will set up the tune solo with a simple three-beat figure that will give it a pared-down New Orleans parade feel, underpinning the melody with a heavy contrasting beat. It is as if Monk immediately hears a way of playing the tune that throw a fresh perspective on it, taking advantage of Taylor’s idea. After the rhythm had been established by Taylor, Monk planned to come in, as he frequently did, for a statement of the first A section of the theme. Then Charlie Rouse on tenor and Sam Jones on bass would fill out the sound and the quartet would play the first “real” statement of the theme.

However, Monk has a lot of difficulty getting Taylor to think the way he does. There are sixteen partial or complete run-throughs of “Light Blue” in the rehearsal, with Monk coaching Taylor constantly, and Taylor gamely trying to follow Monk’s lead. A good deal of the rehearsal is spent in simply coordinating where Monk wants the downbeat to be.

After the rehearsal, there were three full takes of the tune. The first has not been released. The second (on disc two of Les liaisons dangereuses 1960) is still a bit shaky, with no drum intro and Taylor playing a role subservient to Monk’s piano. Rouse’s entrance in this take is also a bit unsure. During Monk’s solo, Taylor drops the rhythm figure they had so carefully rehearsed, and the tune suddenly sounds conventional. After Monk’s solo, Rouse returns for the theme and Taylor picks up the rehearsed figure once again.

In the final take, the one Romano chose for his proposed LP, A.T. begins with the rehearsed figure and Monk comes in much as planned in the rehearsal. However, the drums are louder than they are in the second take, and Taylor continues to play the rehearsed figure under Monk’s solo. Rouse comes in and begins to improvise, and things finally seem to jell, but the take breaks down.

The listener, of course, was only supposed to hear a finished version of the tune, and even though none of the takes was completely satisfactory, the third one gets as close as we will ever hear to Monk’s idea. It is unique in Monk’s discography, because the drums are so prominent and so contrapuntal. On first hearing, it sounds herky-jerky, “wrong,” as Monk’s ideas so often do on first hearing. After you take the trip through the rehearsal and hear the second take, it makes sense – much as so many of Monk’s tunes do after you have become accustomed to their direction.

This is one of the greatest gifts of Les liaisons dangereuses 1960. It lets even confirmed Monk disciples experience – possibly for the last time – a temporary disorientation followed by artistic revelation that reminds us that Monk did exactly what he wanted to do, and only asked us to give him our ears. It brings Monk’s utter originality into fresh focus one more time.

More:

The Jazz Loft According to W. Eugene Smith:

Director Sara Fishko produced and voiced a series of radio pieces based on the film with New York public station WNYC. Here is the episode that deals with the rehearsals for the Town Hall concert. The last six minutes are particularly noteworthy.

Transcript of “Light Blue (making of),” from Thelonious Monk: Les liaisons dangereuses 1960 (Sam Records, 2017) Transcript and music descriptions by Steve Elman.

TM is Thelonious Monk. AT is drummer Art Taylor.

RUN-THROUGH 1: Drums start, apparently AT just noodling around with a two-beat feel, sort of “rest-2-3-rest.” Monk plays the A section of “Light Blue” with him, but as if he just testing out the line, not attempting to coordinate.

TM: Why don’ you keep doin’ that, what you just doin’, what you was doin’ right there. What was you doin’.?

(Two beats from AT, then two more, then two more, in the same jerky feel)

TM over: Yeah, keep doin’ it.

(Studio crosstalk, in which you hear:)

TM: You got that.

RUN-THROUGH 2: AT adds a third beat to the motif, starting on his bass drum, “1-2-3-rest,” now with the notes of the drums ascending in pitch, played seven times. Then Monk comes in with the first two notes, over AT’s 1-2. AT is surprised by Monk’s entrance, stops.

AT: Uh-oh.

TM: Go on.

RUN-THROUGH 3: AT plays the three-note figure again, four times. Monk comes in at the same place as before, gets through the first A, bassist Sam Jones joins in, and AT stops again.

(It seems as though AT is hearing his accents as “on the beat” of 1-and-2-and-3-and rest, which means he would expect Monk to come in on the rest, but Monk wants to hear AT on the OFF beat – OFF-1-OFF-2-OFF-3-, leading directly to the first note of the theme in the space that AT is expecting the “and.” AT feels the rhythm is wrong.)

TM: Keep on. Keep on doin’ it.

AT grunts as if he’s not feeling it.

TM: Don’t let me – You know what I’m sayin’? You get it? Just keep what – in mind what YOU doin’.

AT (mentally shrugging his shoulders): Awright.

RUN-THROUGH 4: AT plays the three note figure again, seven times. Monk comes in, plays the first four notes, stops. AT keeps going, plays the figure six more times. Monk comes in as before, but misses the first note of the theme, grunts. He gets through the A, Sam Jones comes in, and AT stops.

AT (over Monk): Uh-oh.

TM: (laughs) Damn, why you stop, man? That, that’s crazy. I mean, I’m tryin’ t’ dig where – I dig where you’re doin’ it.

(Studio crosstalk, inaudible.)

RUN-THROUGH 5: AT plays the three note figure again, slower, six times. Monk comes in. AT slips and stops again.

TM: Huh! Why you stop, man? Just keep doin’ what you doin’. ‘Cause it was good time.

AT: Huh? Well, it wasn’t –

TM: Damn if it wasn’t.

(Studio crosstalk, including female voice.)

AT: Didn’t sound like good time t’ ME, man. (He snaps his hi-hat cymbal once.)

RUN-THROUGH 6: AT plays the three note figure again, three times. Monk comes in, AT stops. Monk keeps playing, then stops.

AT: Doesn’t sound like good time t’ me.

TM (annoyed now): Just keep on doin’ it. I’ll come in. You just keep doin’ that. Keep on doin’ what you doin’.

AT (sheepishly); OK.

TM: Forget what – y’ know, if it mixes you up, just close y’ ears t’ what we doin’. You know what I mean? Don’t close y’ ears to the TEMPO, just close y’ ears t’ what we doin’. If you can’t hear what we playin’, then play that part.

AT: Awright.

TML You dig? [pause] Awright, you got it.

RUN-THROUGH 7: AT plays the three note figure again, four times. Monk comes in at same place, and plays both A sections. AT is still not secure about where the beat is, and he begins to lose his place. Then saxophonist Charlie Rouse and Jones come in to restate the A sections, but Monk, Jones, and AT drop out before the end of the first A phrase. Monk makes a noise as the players stop – apparently, he has signaled them to do so.

TM (to AT): You fucked up. Just keep your – I told y’, don’t listen to – y’ dig, just keep countin’ to y’self.

RUN-THROUGH 8: AT plays the three note figure again, four times. Monk comes in at same place, and plays both A sections, but doesn’t quite finish the second. This time, AT seems to find his place – the drums finally begin to cohere with the theme.

TM: Mmm. You changed.

AT: Huh?

TM: See, that, that – uh, uh, uh – bass drum is on the AND. It’s on the upbeat, you dig?

AT: Well, what was I playin’ it on?

TM: You changed, and started comin’ down on the beat. You dig what I mean? The bass drum –

AT: I didn’t change from where I started.

TM: Huh?

AT: I didn’t change from the way I started.

TM: Yes you did. Yes you did.

AT: Yeah? Oh, yeah? OK.

TM: See, the bass drum is on the upbeat, you dig?

(Four “recording” studio signals.)

TM: You know, when you comin’ down on the, on the DOWN beat, you know, on ONE, you goin’ ONE on the bass drum, you know you’re wrong. You dig?

RUN-THROUGH 9: AT plays the three note figure again, five times. Monk comes in at same place, and then AT loses his place and stops. Monk keeps playing, then stops and imitates how the drums should sound.

TM: Mm-mm-pah-PAH. Oom-boom-pah-PAH. Oom-oom-pah-PAH. Boom-oom-PAH. Boom—oom-PAH.

(Two “recording” studio signals.)

TM: Boom-PAH. Boom-PAH. Boom-PAH.

AT (bemused, over Monk’s scatting): I started somethin’, right?, and I can’t finish it.

(Studio laughter as Monk continues to imitate the drums.)

AT: Shit.

TM (by now stomping his foot in alternation with his vocal noises): Oom. Ooom-BAH. Oom BAH.

AT: Awright.

TM: (Chuckles) Boom-pah-PAH. You dig?

(Studio crosstalk, including a male voice with a French accent, presumably that of producer Marcel Romano, and a female voice, possibly that of Nica de Koenigswarter. Monk continues to talk over this.)

TM: You dig? Shit, I don’t know. You dig it? You dig how it go? [to Sam Jones] You dig how it goes, Sam, don’t you? [to AT]. You just DUMB. Dumb muthafuckah.

(Studio laughter, but Monk seems to be half-serious.)

TM: Dumb muthafuckah.

(A few more studio chuckles, with a female voice saying, “I just wanted a cigarette.”)

AT: Awright.

RUN-THROUGH 10: AT plays the three-note figure two times, now possibly with both sticks striking the toms at the same time. Monk begins counting the time under him, softly at first, and then so he can be heard over the drums. AT plays the three-note figure four more times, then stops.

TM: One-and-two-and-three-and-four, and one-and-two-and-three-and-four. You dig it?

AT: That’s not the problem, y’know. But I mean, I’m doin’ this, this here, but I never did that before.

TM: Well, do sumpin’ else, but keep the same time. Y’know? Keep the same kinda thing goin’.

AT: Awright. Awright.

TM: You dig it? You got to keep doin’ that.

(Five studio signals.)

TM: But y’ have to keep that time, y’ know?

AT: Awright.

TM: See, y’ goin: and TWO and. And FOUR and. Y’ dig? [AT starts again, but Monk interrupts him.]

TM: Y’see, on the and of the THREE, and FOUR and, and on the and of the ONE, and TWO and. Y’ dig? [pause] Go ahead.

RUN-THROUGH 11: AT begins the tune, but this time plays bass drum and two snare shots, followed by bass drum and two low tom shots, followed by bass drum and two high tom shots, followed by bass drum and two low tom shots, followed by bass drum and two high tom shots, followed by bass drum and two snare shots

TM (over drums): Don’t rush. Same time. Take y’ time when y’ do it.

AT stops as Monk grunts the tempo he wants and snaps his fingers along with .the grunts.

TM: Mm-mm-mm-mm. Mm-mm-mm-mm. Y’ dig? Take y’ time.

(AT tries again, at a slower tempo. He plays bass drum and two high tom shots, bass drum and two snare shots, bass drum and two low tom shots, bass drum and two snare shots.)

AT: Yeah.

TM: Go on. Keep on doin’ it.

RUN-THROUGH 12: AT begins, Monk comes in, and then SJ and CR come in for a nearly-complete statement of the theme. AT grunts and stops, but the other three go on, apparently until Monk waves them to stop.

AT: Let’s start again, Monk. I’m sorry.

(Monk plays the theme solo and counts along with his playing.)

TM: AND two and three and. Y’ dig? [stops playing] It’s on the AND of one AND two and, y’ dig? Y’ always can find y’self, because you, on the first beat, y’dig, y’ find the first beat, the ONE, and then y’ bass drum comes on the AND, y’ dig?

AT. OK. OK. OK.

(Six studio signals.)

RUN-THROUGH 13: They begin again and get through a statement of the entire theme. Monk stops, but Rouse continues for a few notes.

TM: Play it slow. Hold it. Y’ dig? Play it slower.

AT: Slower?

(Monk counts time, slower than it was played.)

TM: BAH-too-tah. BAH-too-tah.

(AT plays the rhythm, slower, and Monk counts the time along with him.)

TM [over drums]: One. Two. Three. Four. One. Two. Three. Four. Yeah. (AT continues playing. Monk listens for a few seconds.) BOOM. Make that bass louder. (pause) Take y’ time, don’t rush it.

RUN-THROUGH 14: AT starts again, and Monk comes in, but apparently the tempo is still too fast, because Monk seems to wave AT to stop as he continues on the piano, slightly slower, and then slowing more as he goes, demonstrating where he wants the tempo.

TM: MMM-tah-tah. Y’ dig?

(Monk plays two notes of the theme and then scats the rhythm where he wants it.) TOOM-tah-tah.

RUN-THROUGH 15: AT plays the three-note figure seven times, with Monk making several entrances but never playing more than a few notes. Finally, Monk starts the theme and plays the full A section, but AT drops out midway through. When Monk starts the second A, AT comes back in and Monk stops. AT plays the figure 13 more times.

TM (over drums): Yeah, just, tah-TAH. Mm-tah-TAH. Mm-tah-TAH. (AT stops.)

AT: Huh?

TM: Mm-tah-TAH. Mm-tah-TAH.

(Six studio signals.)

TM: (filling the space before “Mm” with a foot-stomp): Mm-tah-TAH. Mm-tah-TAH. (AT joins him, playing the figure on Monk’s scats.) Mm-tah-TAH. Mm-tah-TAH. Mm-tah-TAH. (Monk stops scatting.]

RUN-THROUGH 16: AT plays the figure two more times, and Monk enters with the theme as before. Rouse and Jones enter on cue, and they play the entire theme. Rouse drops out and Monk begins to improvise over Jones and AT. Rouse enters again and they again play the entire theme through.

AT: Oh, keep goin’.

TM: Yeah, that would’ve been crazy, if you kept on doin’ that.

AT: Oh, you thinkin’ take?

TM: Why you stop?

AT: I didn’t know you was thinkin’ take.

TM: Woulda been solid if – We’ll listen to it.

(Pause. Then, to Marcel Romano in the booth:)

TM: Play it back, please?

ROMANO: Yes, sir.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Great writing, congratulations! Thanks for posting! I will watch the film, however apparently finally Art Blakey authored the music.

Happy 2006!