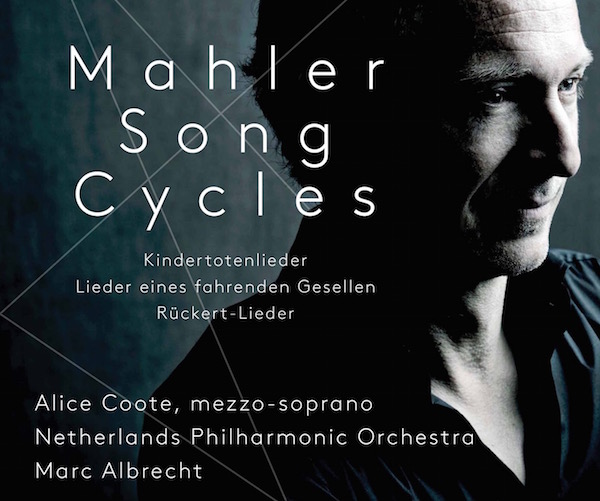

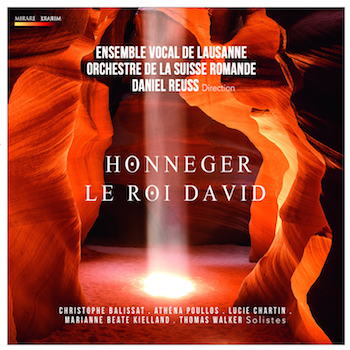

Classical CD Reviews: Alice Coote sings Mahler and Honegger’s “Le roi David”

A wonderful new performance of Mahler’s three orchestral song cycles; Daniel Reuss’s account of the oratorio Le Roi David is so good it’s basically flawless.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Here is a wonderful new performance of Mahler’s three orchestral song cycles featuring mezzo-soprano Alice Coote and the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra (NPO). Her interpretations in each are involved, deeply personal, and psychologically intense.

In the Gesellenlieder, for instance, the hushed intensity of Coote’s singing in the refrains during the final song are as compelling as the anguish she pours into the “O weh” iterations of “Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer” and the bittersweet joy she teases from “Ging heut’ Morgens übers Feld.”

Her performance of the Rückert-Lieder is broader, if similarly stylish, spanning the playful charm of “Blicke mich nicht in die Liebe”; the rapt, fervent devotion of “Um Mitternacht”; and including a thoroughly affecting “Liebst du um Schönheit.” But she’s at her best in “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen,” the last verse of which is pure, time-stopping magic.

The Kindertotenlieder bring out some warm, burnished singing in Coote’s lower- and middle registers. In these songs (“Nun seh’ ich wohl, warum so dunkle Flammen” and “Wenn dein Mütterlein”), the performances are especially absorbing: dark and intimate. And when it comes to moments of pure drama, she delivers. The opening half of “In diesem Wetter!” is weighted with grief, while the first song, “Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgehen,” is all numb shock. No matter how you cut it, this is a great Kindertotenlieder.

Throughout, Coote is expertly accompanied by the NPO and conductor Marc Albrecht. There’s some particularly excellent wind and brass playing to be had: Mahler’s sometimes odd scoring for instruments like the piccolo (which gets an opportunity to show off its lowest range in “Um Mitternacht” during the Rückert-Lieder) come across with warmth and clarity. The orchestra’s strings acquit themselves well, especially in the Kindertotenlieder. And Albrecht cements his reputation as a gifted Mahler conductor, leading performances that are well paced, fluid, and thoroughly in-the-moment.

Pentatone’s engineering is typically fine, though keyboards and harps sometimes sound a bit distant. Otherwise, there’s not much to complain about here.

These days, you’re probably more likely to encounter Arthur Honegger’s name as a footnote in a program note on Stravinsky than to hear any of his music in concert. Even if he’s fallen out of favor (wrongly, I’d argue), it’s always a joy to come across strong, new recordings of his music. Daniel Reuss’s recent account of the oratorio Le Roi David for Mirare is one of those, so good it’s basically flawless.

The piece itself is a reduction Honegger made of his 1921 magnum opus, originally a four-hour staged spectacle on the life of King David, for dancers, narrator, soloists, chorus, and a peculiar, 17-piece, wind- and brass-heavy instrumental ensemble. Too costly to stage widely after its triumphant Swiss premiere, Honegger crafted the present version, which condenses the action to about an hour while linking the story through the narrator’s text and keeping much of the musical ensemble intact. It is, in practice, a direct and concentrated piece, one that breathes devotion while never veering off into any sort of cloying piety.

Indeed, the music can be plenty brash and acerbic. Throughout, there are echoes of 1920s Modernism plus bits of jazz and plainchant. Hints of Weill’s direct style in turn up, too, if less of his insolence. Similarly, the rhythmic episodes of David often seem to anticipate Carmina burana, though Honegger’s music offers greater expressive depths than does Orff’s. Above all, the music is strongly lyrical, suggesting, despite the clear, Germanic elements in Honegger’s style, his complete absorption of the chanson tradition of Gounod, Faure, Duparc, and others.

The present performance revels in that songfulness. Throughout, the singing of the Ensemble Vocal de Lausanne is superb: rhythmically secure, of pristine diction, excellent balance, and warmth of tone. Similarly fine are the contributions of members of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, who play with impellent energy and lots of character – some of the cheeky woodwind writing (like the leaping oboe figures that open the second part’s “Cantique de fête”) really jumps out.

The soloists – soprano Lucie Chartin, mezzo-soprano Marianne Beate Kielland, and tenor Thomas Walker – are smartly cast. Chartin floats through the higher writing for her part, always full and clear, her voice never sounding pinched. Her duet with Kielland in the “Lamentation de Guilboa” is beautifully etched. Walker sometimes sounds a bit strained in his upper register (sort of like René Kollo in his prime) but that generally adds an urgency to his portrayal of David. Christophe Balissat turns in a fervent account of the narration while Athena Poullos is a wild-eyed Pythonisse.

Reuss presides over everything with a sure hand. The whole performance is brisk and fresh – kind of like a Negroni for the ears: entertaining but also moving. In all, a keeper.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Alice Coote, Arthur Honegger, Le Roi David, Mirare, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra