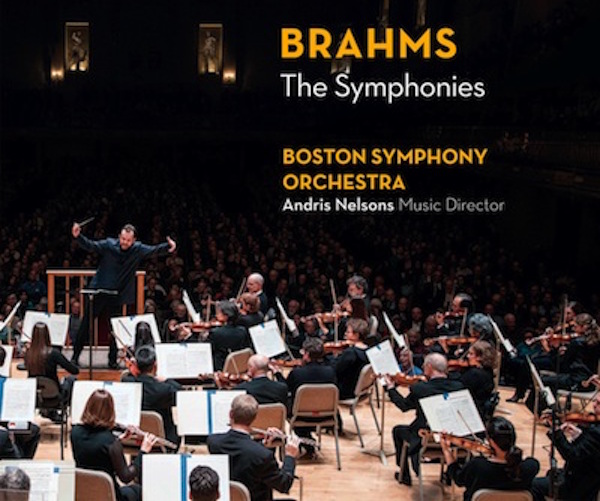

CD Reviews: Andris Nelsons conducts Brahms and Christian Gerhaher sings “Die schöne Magelone”

The BSO sounds as robust and responsive as they do when they’re on their best behavior at Symphony Hall. Christian Gerhaher sings Brahms with intense beauty and focus.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

You might be surprised to know that, given the frequency with which the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) plays the Brahms symphonies, the ensemble has, before this year, only recorded the complete cycle of them twice: once each with Erich Leinsdorf and Bernard Haitink. So Andris Nelsons’ traversal of the set on the orchestra’s in-house label, BSO Classics, isn’t actually overflowing the market, at least as far as the BSO’s contributions to the Brahms discography are concerned.

That said, how does this new album stack up with the Szells, Karajans, Soltis, Bernsteins, Böhms, Kleibers, Furtwänglers, Giulinis, and Walters already out there? Like most all of them, it’s well played: the BSO is a great Brahms orchestra and knows these pieces as well as any. Interpretively, these performances probably aren’t going to change your mind about any of this music one way or another. Nelsons’ Brahms isn’t factious, overly forceful, or compelling in any out-of-the-ordinary way. On the contrary: it’s solid, straightforward, and satisfactory. It likely won’t ruffle anybody’s feathers, which, depending on your perspective, can be taken either as high praise or a damning indictment. Or something in between, which is probably the most correct response to this set.

The two symphonies that come off best in Nelsons’ hands (in this recording, at least) are the First and Third. In the former, Brahms’ debt to Beethoven – the character of the melodies and development of the motivic writing – comes over with remarkable clarity, in large part the result of the finely-manicured playing Nelsons draws from the BSO.

In the Third, the stormy waves of the outer movements crest with force and logic, and the serene second one is breathtaking in its calm beauty. Only the third movement is a letdown, overall too slow and fussy to really come to life. Otherwise, this is an almost ideal Brahms Three: the way Nelsons brings together all its motivic threads at the end of the finale is magnificent and demonstrates his strong command of the music’s tricky rhetoric.

The even-numbered symphonies offer a few more quirks. In the Second, the outer movements trudge: even with his omission of the exposition repeat (which is also cut in the First Symphony), Nelsons’ first movement clocks in a good ninety seconds slower than Karajan’s repeat-less 1978 reading (as well as a minute longer than HvK’s similar 1964 version), and you feel it. Then, during the finale, it’s almost as though Nelsons wants you to hear the placement of every single eighth note in it, so deliberate is the articulation and pacing of the movement. Expressively, it’s clinical, episodic, and devoid of joy.

But the middle movements are quite fine. The second is fluent and passionate, the third light and crisp. The contrast between the four, though, is peculiar: the lumpish first and fourth seem to belong to a completely different piece.

As for the Fourth, it’s suitably grim. The first movement is full of turbulence and, in the recapitulation, a marvelous sense of novelty. Tempos, as in the Second, are a bit ponderous in the middle two, though they’re both played with color, and the finale builds to a terrific climax.

The BSO sounds, well, as robust and responsive as they do when they’re on their best behavior at Symphony Hall. They clearly enjoy playing for Nelsons and give him their best. All of the principal wind players acquit themselves marvelously in their various solos, as do first horn James Somerville and concertmaster Malcolm Lowe.

Sound-wise, the recording is full and well-balanced: from a technical angle, it’s another triumph for the orchestra’s award-winning engineering team.

Over the last few years, Christian Gerhaher has cemented his place as one of the finest interpreters of Romantic lieder of his generation. His latest recording, of Brahms’s somewhat-neglected Die schöne Magelone for Sony Classical, more than lives up to his previous Schubert, Schumann, and Mahler discs.

At the heart of it is singing of intense beauty and focus. Gerhaher’s a singer with a magnificent instrument: full of power but also capable of great nuance and delicacy. In the robust movements, like the bouncing, opening “Keinen hat es noch gereut,” he’s all bounding energy, rich in passion and fire. Even then, though, a supple lyricism shines through his interpretation.

This latter quality blossoms fully in the slower-tempo songs, “Liebe kam aus fernen Landen” and “Ruhe, Süßliebchen” among them. And it teams winningly with the pathos and drama that mark “Wie soll ich die Freude, die Wonne denn tragen?” and “Wir müssen uns trennen.”

Through the whole reading, Gerhaher turns in a performance that’s rhythmically vital and tight. His diction is excellent. And the clarity of his singing – both in tone and expression – helps bring these poems’ sometimes cumbersome (and confusing) narrative vividly to life.

Of course, Gerhaher alone can only bring this music so far: he’s joined by Gerold Huber, who turns in a rich, immaculate account of the songs’ piano part. Brahms’s keyboard writing in Magelone is famously challenging and involved (rather on par with Beethoven’s piano writing in the Violin Sonatas). Huber delivers it all with energy and color, plus a rhythmic precision that perfectly matches Gerhaher’s approach to the vocal part. Together, theirs is no less than a marvelous Magelone.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Andris Nelsons, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Brahms, Christian Gerhaher