Poetry Review: “The Thin Wall” — Haphazard Resonance

Unfortunately, poetry doesn’t sell and doesn’t get made into movies.

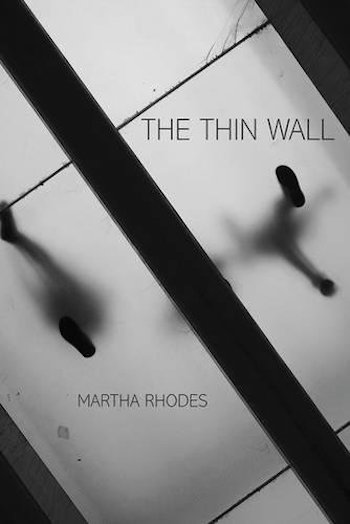

The Thin Wall by Martha Rhodes. University of Pittsburgh Press, 53 pages, $15.95.

By Ed Meek

In the last twenty years MFA Programs have surged and multiplied (hundreds of programs and thousands of yearly grads) and have become more academic. In fact, many writers who get MFAs now go on to get PhDs. In any case, academics, when they can, aim to control and define the arts. This happened with fiction back in the 1970s and 80s, but by the 90s, the public got fed up with all those post-modern pseudo-intellectual novels full of narrators talking about the novel and novels with multiple endings or with no endings at all and fiction returned to what it does best: telling stories that are well-written because those are the stories that sell and get made into movies.

Unfortunately, poetry doesn’t sell and doesn’t get made into movies. Poetry is more like painting and sculpture except it doesn’t look so good on your wall or in le jardin. But since there are so many MFA Programs, publishers figured out that they could sell books of poems to all those MFA grads. At the same time, publishing and printing have evolved so that publishers can print on demand and no longer have to invest in a few thousand copies of a book before putting it on sale so that it is much easier now to get a book published by a small, independent press or even to publish it yourself. The result is that we have thousands of books flooding the market. Yet there are few critics of poetry who have been able to define the poetry of our age. In fact, for the most part, no one even criticizes poetry. Instead, people just write positive reviews of poetry that they like. This creates an odd situation where there are a number of poets who write prose that is merely broken into lines. And there are poets whose poetry really is aimed at an academic audience.

Martha Rhodes is a prominent figure in the landscape of contemporary poetry. She teaches at Sarah Lawrence and in the MFA Program at Warren Wilson College; she is the Director of Four Way Books in New York. Her new book, The Thin Wall, has been published by university of Pittsburg Press. It is a slim volume of 53 pages divided into three sections, each with a number of poems, usually one to a page, with no titles. The sections are: (Burden of Inheritance), (Yard Fire), and (Looking Down). Those section titles are in parentheses. Here is the first poem:

buckets of

and heads wet from the dunking.

A witch ‘round every corner.

Ladders.

Jury and judge.

A pond of bodies bobbing, condemned.

And nineteen nooses wait.

That seven-gabled house.

Girls run the streets accusing

the accused. In Salem Village,

Goody Proctor bears her child in jail.

Our party pays to tour the next grey house.

This is our inheritance here in New England: the witchcraft and the hangings. Throw them in the pond to see if they float and if they do, they must be witches! The narrator sees this in her mind as if she is on a tour. There’s wit in the last line—that we should pay to see this past of ours. But why “buckets of” as a separate line rather than: There are buckets of apples. The off-rhyme with judge is there either way. Why isn’t the poem titled “That seven-gabled house” rather than insinuating that line in the middle of the poem awkwardly just to set up the last line?

Other poems in the first section are not so resonant. One poem begins: “The air was heavy with blood. /The boys washed off in the Merrimack.” That’s a little too heavy handed. So too another poem that begins: “Both of us under one boy or another./That’s how we spent our senior year.” Doesn’t that sound like the beginning of a Chelsea Manning confession in Vogue? Did anyone actually spend her senior year under one boy or another? Another poem begins: “Boys, girls, some of them siblings,/spawning in bathtubs all over town./ Drown them?” This could be out of The Beans of Egypt Maine, where kids crawled under the porches and no one knew to whom they belonged. There’s a kind of condescension at work here, the poet assuming personas that do not ring true.

The second section is called (Yard Fire). It is about relationships. The first poem is about loss:

The bread from meit stole. I felt

like a flour sack,

pecked, consumed,

scattered. Enough dust

to dust. You, just gone.

That certainly captures the feeling of devastation when someone dies—the hour of lead, Emily Dickinson called it. Of course, Emily’s poems were written before God died. Now there is no recourse. Nice assonant sequence at the end of the poem.

The last section is called (Looking Down). In a couple of poems the narrator is in fact looking down at another or another’s body. There’s humor in this section. One poem begins: “Your dog’s dinner. /What you feed the chickens. /The mud at the bottom of the Charles. /I’m what washes up on the Merrimack’s shore.” The poet is personifying all that’s rejected and cast off. “I’m everyone’s former friend. /I’m his former wife.”

Poet Martha Rhodes — a prominent figure in the landscape of contemporary poetry.

In the final poem of the book, the title comes up: “Nothing is the thin wall of glass (as thin as skin)/ just over there…nothing grabs us all, good or bad, boy/girl popular, un-, you…” So, when you read that, you might agree, Yes! It really does. Or you might not. “Nothing” separates and gets to us all. But can the word “nothing” when used as the subject of a sentence have agency? “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall…” Frost said and maybe Rhodes is playing off the Frost line. The poet is attempting to connect with the reader, “nothing grabs us all,” but Rhodes’s perspective is too removed from our experience to resonate.

In a recent interview in The Paris Review, Ben Lerner talks about a problem he sees as endemic to poetry.

The main demand associated with lyric poetry is that an individual poet can or must produce both a song that’s irreducibly individual—it’s the expression of their specific humanity, because it’s this intense, internal experience—and that is also shareable by everyone, because it can be intelligible to all social persons, so it can unite a community in its difference. And that demand… is impossible.

Of course it is not impossible. It is difficult, particularly today in our fragmented world. Whitman said, “to have great poets, there must be great audiences.” Here’s hoping that the recent popularity of writing, reading, and performing poetry leads to a better sense of what good poetry is and what it is good for. Literary magazines call for poetry that pushes the boundaries; we would be better off with poetry that makes connections with tradition but reflects our age.

Ed Meek is the author of Spy Pond and What We Love. A collection of his short stories, Luck, came out in May. WBUR’s Cognoscenti featured his poems during poetry month this year.

I appreciate your desire for more criticism in poetry — and I had some thoughts about yours.

For example, you ask: Why is “buckets of” on a separate line? I think its placement brilliantly serves to describe both the apples of the line above, and, horrifyingly, the “heads” below, referencing the heads the women dangling from ropes. Also I had assumed “The seven gabled house” to be where the narrator was speaking from… I like how it follows the numbered phrase about the nooses, again genius in connecting the two lines, evoking the a sense of evil underlying the facade of wealth, power, and elegance.

You say “we would be better off with poetry that makes connections with tradition but reflects our age.” First, I think in some ways, Rhodes does exactly that, stylistically bringing to mind Emily Dickinson and thematically grounded in the era of the Salem witch hunts. But she makes it her/our own. I am somewhat enriched by this knowledge reading Rhodes, but those allusions aren’t necessary for me to appreciate her poems. Which leads me to the second point: why do we have to choose? Where would we be without art leaping out of the confines of tradition? And whose tradition should we be connected with? It seems an academic concept that understanding art depends on knowledge of its past, and that poems work best in the context of art that came before them. What was Emily Dickinson’s precedent? Rather, isn’t it more in the spirit of art for poets to express their true voices–and if they evoke the past in some way, okay well, great! We’re all connected by sharing this planet, and art resonates when it touches those connections — whether historically or culturally or just plain humanly. How exciting is a world that accommodate multiple points of view– from those connected with tradition to those breaking free of it?

Thanks for your comment Ms. Brill. I am a big fan of Emily, although, I side with Berryman who said: “For whom shall I write? For the dead, whom thou didst love.” It certainly helps in understanding art to have some knowledge of past art. Artists are often responding to other artists alive and dead.